CONTENTS

About the Book

An organic adventure for the whole family

Memoir, natural history guide and cookbook all in one, Seaweed and Eat It is packed with delicious recipes, wild feasts and fascinating folklore.

From identifying edible and medicinal wild foods from sorrel to seaweed, shellfish to shaggy ink caps to growing a wild garden or window box in the city, this is an essential book for the family that wants to get back to nature.

If you care about your food and where it comes from, this inspirational guide to wild food and how to cook it will ensure that mealtimes are always an adventure.

So give the supermarket a wide berth, let the kids get muddy and get foraging!

To our fathers

Adair Houston, 3 June 19265 May 2003

Gavin Younger, 3 June 19263 September 2003

With love and appreciation

FOREWORD BY AA GILL

Years ago, before either of us had families, Xa and I spent a summer in Scotland cooking. I was supposed to be teaching local stuff, and Xa and a couple of others, including Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, were supposed to be learning something. Actually, we all hung out in a big old kitchen making a mess, producing heroic amounts of fantastically energetic, robust and occasionally inspired food, to feed each other and anyone else who put their head through the back door.

Even after all the years and all the dinners, I can remember some marvellous soups: Parton Bree, made with little green crabs discarded from the bottom of lobster creels Hugh made a rather piss-elegant version with local langoustines; Braw Bree from a hare off the hill; Scotch broth with prunes; Cranachan with soft fruit from the kitchen garden.

The point was to source as many ingredients as possible from one glen. I shot a fat stag in the heather, caught brown trout, made the others dig tatties and kale, walked up blaeberries. I went to see Peggy Mackenzie, a retired keepers wife, who agreed to teach me how to make haggis in exchange for a couple of rabbits. With the softest of voices and the gentlest fingers, she showed me how to make haggis from the pluck of the little four-horned Harris sheep, whose blood made black puddings, and whose delicate legs we salted. I baked on an ancient stove: boiled cakes, drappit scones and slow-baked rhubarb jam flavoured with cloves, and a great peppery black bun. In the kitchen we made Crowdie, scented with wild garlic, and ate it with warm farls of oatcakes.

Very quickly the food and the place became indistinguishable, merged into one thing. Cooking and walking, stalking and digging, tying a hook and pricking your thumbs for brambles, all came together as part of a single experience. It was one of my happiest summers cooking an Arcadian month or two.

Xa and Fiona have now produced this wonderfully practical, bountiful and inspiring book, giving not just a sense of place and season, but adventure to what our children eat. When we did it twenty years ago, it was for fun; today it is still fun, but it contains a more important message of care and connection to the land and ingredients. Most food books begin at the end of the gathering process; this one, quite rightly, starts at the beginning. I love it not least for its reminder of the taste of a happy late summer in the Highlands.

Adrian Gill, 2007

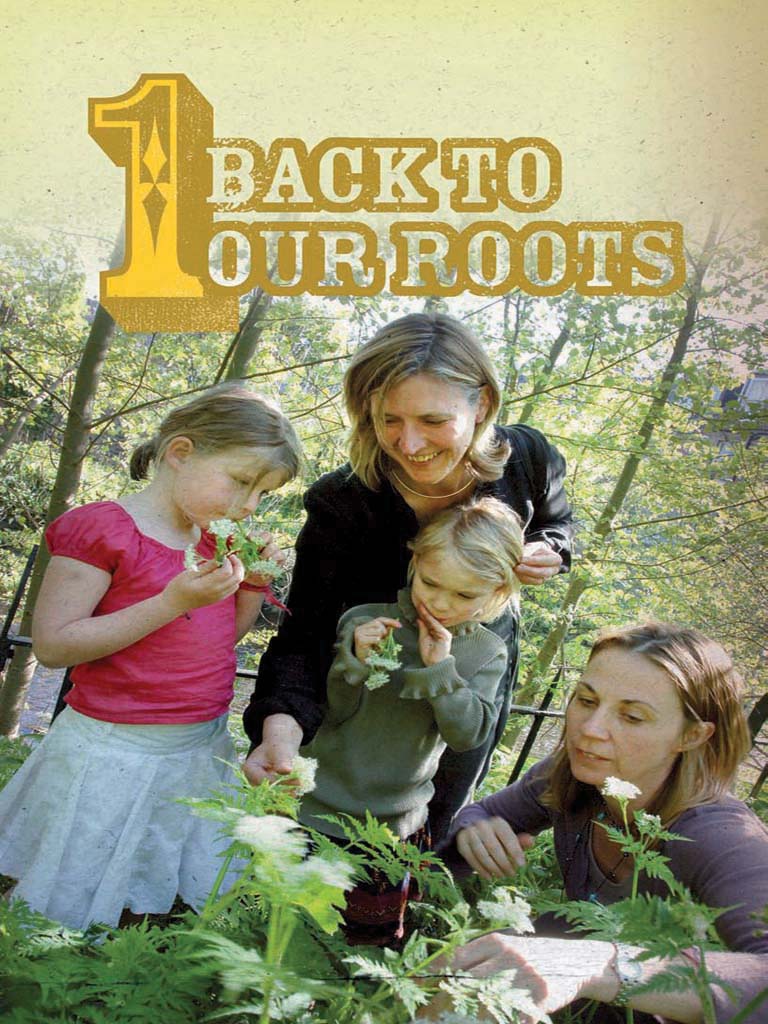

1. BACK TO OUR ROOTS

Seaweed and Eat It is the result of a serendipitous meeting in a primary school playground of two women with a love of food and the outdoors, and a large quota of maternal guilt that our children might grow up with no real connection to the countryside and where their food comes from. We wanted to create, for our families, some adventurous memories of childhood, like we were lucky enough to have, and instil a love of fresh food and cooking along the way.

We hope you take this book as a recipe for outdoor fun and informal eating, whether you have kids, or are just a kid at heart, whether you are rekindling childhood memories, or are taking your first foraging steps beyond buying elderflower cordial in the supermarket.

FIONA

At the time, it seemed like every evening after school, my mother would use her child labour force of four to pick an industrial amount of brambles to make a years supply of bramble jelly. Harvesting the mushrooms from the field in front of our house felt like Christmas had come early; we made vats of delicious buttery, creamy mushroom soup that my father would swoon over. The standing stake nets on the tidal mud flats of the Solway Firth were another opportunity for foraged food. We waited until the fishermen had cleared the nets of salmon and sea trout, then went in and collected from the muddy shallows the flounder that were not deemed worthy of eating. My mother, who has lived her whole life on the same farm, instilled in us a sense of place, and her no-nonsense practicality will always be that little voice in the back of my head, telling us to just get outside and get on with it, and well rustle up good food however many friends show up in the kitchen at meal times.

That flounder was, looking back on it, real food to me; picked fresh and brought home to fry up, not the fancy food heavy on cream and sauces I learnt on a summer cooking course my mother forced me to go on, thinking that I would never bag a husband unless I knew how to make mayonnaise by hand. Her insurance policy backfired when I increased a dress size in just three months; she didnt realise that she had given me all the culinary education I needed.

Anyway, we all left home, no more bramble picking or mushroom soup, we didnt really pick much of anything other than picking up take-away Chinese. My husband, Duncan, shared a similar childhood to me, school holidays spent tramping the Irish countryside with his mother and his Irish relations, in search of fish, mushrooms and frockens. My mother-in-law, Charlotte, used to love my reaction when she told me childhood stories of shooting starlings with an airgun then eating them after roasting them on the fire.

We spent a decade living in Washington DC, getting increasingly frustrated with the peaches from Super Fresh, the local supermarket, that were anything but super fresh; they went mouldy in the fruit bowl before they ripened. Where were those famous Georgia peaches, rosy and sweet, still warm from the sun?

Despite our frequent wilderness camping trips in the Rocky Mountains and on an island in the St Lawrence River, my foraging tendencies were put in the cold storage part of my brain in my quest to climb my way up the journalistic ladder. Our lives were focused on conspiracy theories and policy platforms, not wild garlic and blossoms. Then, one spring, I flew home and set out for a dog walk along the river with my sister.

Val stoops to pick some green leaves on the riverbank. What is that? I ask, embarrassed at my ignorance.

Wild garlic, comes the reply.

Oh, really? Thats what it looks like, I reply. Ive always wondered. Pause. I cant believe I didnt know that!

Maybe it was sibling rivalry that sparked my curiosity, but it was time for us to get back to our roots. Time to make sure that our children would not be consigned to thinking rock-hard, mouldy peaches was the norm, or that all vegetables came wrapped in cling film, not dirt.

In August, we went for a walk along the beach with our American friend, Andrew, and his Chinese friend, Wei. Her eyes were fixed on the forests of kelp dancing in the waves at low tide.