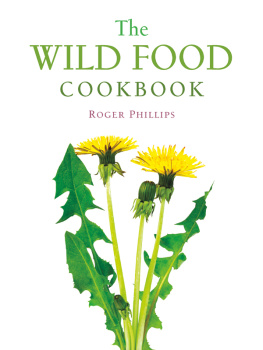

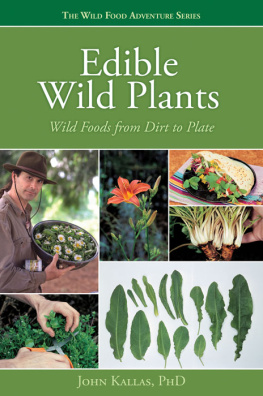

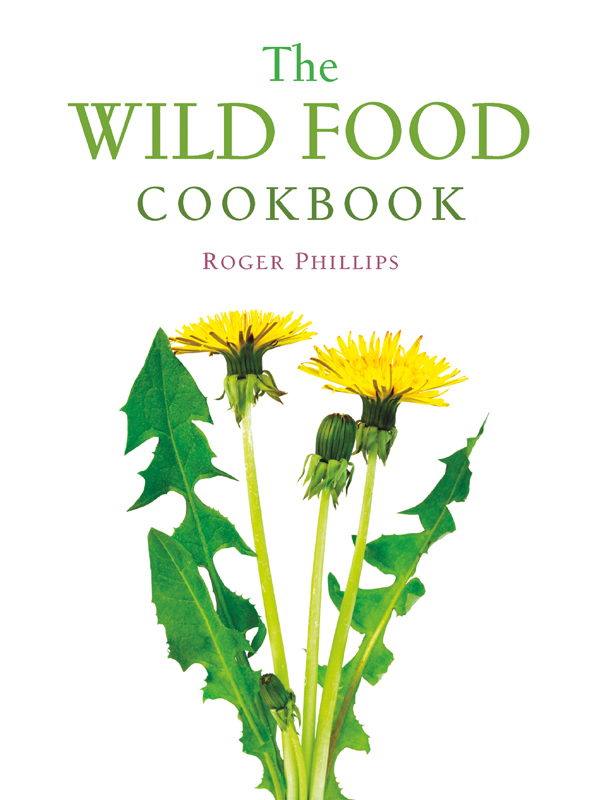

The

WILD FOOD

COOKBOOK

ROGER PHILLIPS

The Countryman Press

Woodstock, Vermont

Copyright 1986, 2014 by Roger Phillips

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages.

Book design and composition by S. E. Livingston

Published by The Countryman Press,

P.O. Box 748, Woodstock, VT 05091

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Phillips, Roger, 1932

Wild food.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Wild plants, EdibleUnited StatesIdentification.

2. Cookery (Wild foods) I. Foy, Nicky. II. Hurst,

Jacqui. III. Title.

QK98.5.U6P54 1986 581.6320973 86-128

The Wild Food Cookbook

ISBN 978-1-58157-218-6

ISBN 978-1-58157-678-8 (e-book)

W hen I was seven, an eccentric, bohemian teacher at my school used to send me and my classmates into the local wilderness of suburban London to find sufficient nettles for our lunchtime soup. Thus began my lifetime love affair with wild food.

When I was 47, I decided to combine my love of nature with my love of food, so I produced a book that would help like-minded people to find, cook, and enjoy some of the numerous wild plants that have been known for centuries to be edible. Once Wild Food was published in Europe, my mind kept wandering to North America. What kinds of edible plants grew in abundance, waiting to be collected and consumed? Finally, curiosity overcame common sense, and I decided to tackle the huge task of exploring the edible wild plants of North America and publishing an American Wild Food . As the venture would take several years to complete and would necessitate traveling thousands of miles to find, collect, cook, and photograph the plants I needed, my wife, Nicky, and I decided it had to be a family affairand we would take our baby daughter, Phoebe, with us.

So twice a year, we packed our bags, displayed ABSENT ON LOCATION signs on our London studio, and went on the road. Everyone thought we were crazy traveling with such a tiny tot (she was three months old when we began), but although there were a couple of occasions when she did succumb to germs and jet lag, basically she loved the excitement of new places and faces; and she soon became an avid berry and mushroom hunterand taster too! How many little English girls of three have visited the Great Lakes and the Grand Canyon, the Cascades and the Appalachians, the Sonoran Desert and Skyline Drive? America has now become her second home, and within minutes of landing on US soil she is saying, Hi, guys, as though she had been born and bred to it.

THE AIMS OF THIS BOOK

In producing Wild Food , I have tried to do two things that I felt had not been covered before in one volume.

First, I wanted to make sure that the book could be used as a basic reference for all the best-known recipes traditionally associated with wild foodcranberry sauce, blueberry muffins, dandelion coffee, lime tea, elderflower wine, cattail shoots, wapato rootsand so I have included all the standard recipes. But second, I wanted to go farther than this. By exploring and developing some of the other fascinating sources of wild food, such as seaweeds and mushrooms, I could show that there were several groups of wild plants that had been left largely unexploited, and yet they provide a great many of the most nutritious and tasty dishes for the adventurous food hunters table.

Two principles have guided my choices throughout. I have included only those plants that can be found in sufficiently large quantities to make eating them worthwhileand, much more important, those plants whose survival will not be endangered by gathering them for the pot. Furthermore, I have tried to select one or two really successful recipes for each plant rather than include all possible recipes. The rationale for this is illustrated by the mushrooms. In the recipes in the mushroom chapter almost any of the 50 or so species that appear in the book can be used successfully. But the actual recipes selected for each species are those that, after numerous testing-and-tasting sessions, I think best suit the flavor and texture of that particular mushroom.

The recipes have been gleaned from a variety of sources. Historical research into old cookbooks, explorers diaries, traders accounts, and anthropological studies of Indian tribes and customs revealed an enormous number of ideas about how to cook wild plants, many of them far too elaborate and impracticable for modern cooks, but nevertheless fascinating reading. I am also indebted to numerous contemporary authors and magazines for recipes I have either quoted verbatim or adapted slightly to suit my ingredients; and last, and by no means least, I have regularly invaded the kitchen of friends and acquaintances to steal their cherished secrets.

As a result of this research, I collected a wide variety of recipesfar more than could possibly be used. So, in order to find out which ones I personally liked the best, I made every single recipe and included in the book only those that seemed really worthwhile, even though it meant rejecting about two-thirds of the material.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

The book is arranged by sections, and the sections, as far as possible, follow the seasons of the year. This means that if you are going wild food hunting in the spring, you will find details about the plants and accompanying recipes appropriate to this time of year in the front sections of the book. Conversely, if you collect some interesting berries or mushrooms in the fall, you can look in the books later sections for ideas of what to do with them. However, should you want to look up a particular recipe or plant, the index, which lists recipes and both common and botanical plant names, will guide you to the entries.

Seaweeds

Seaweeds must be, without doubt, one of the most wasted natural resources in North America as well as in Europe. Fortunately, our ever-growing interest in Japanese cooking is making us more aware of the benefits that the numerous seaweeds on our coasts can provide.

Among the most nutritious plants in the world, seaweeds contain high proportions of proteins, minerals, and vitamins, notably vitamins A, B1, B12, C, and D. Sea lettuce, for instance, has more vitamin Athe growth vitaminthan butter does, and many of the green seaweeds contain a higher concentration of vitamin B12 than can be found in liver. Seaweeds contain about 2.5 percent protein by weight, so that laver, for one, contains a higher proportion of protein than do soybeans. Another virtue: all species are rich in minerals and trace elements because seawater has almost exactly the same proportion of minerals as human blood.

Next page