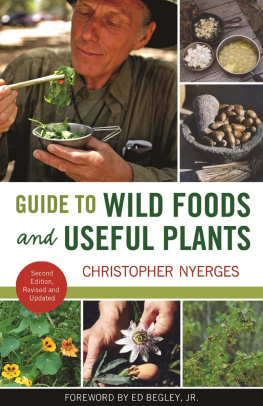

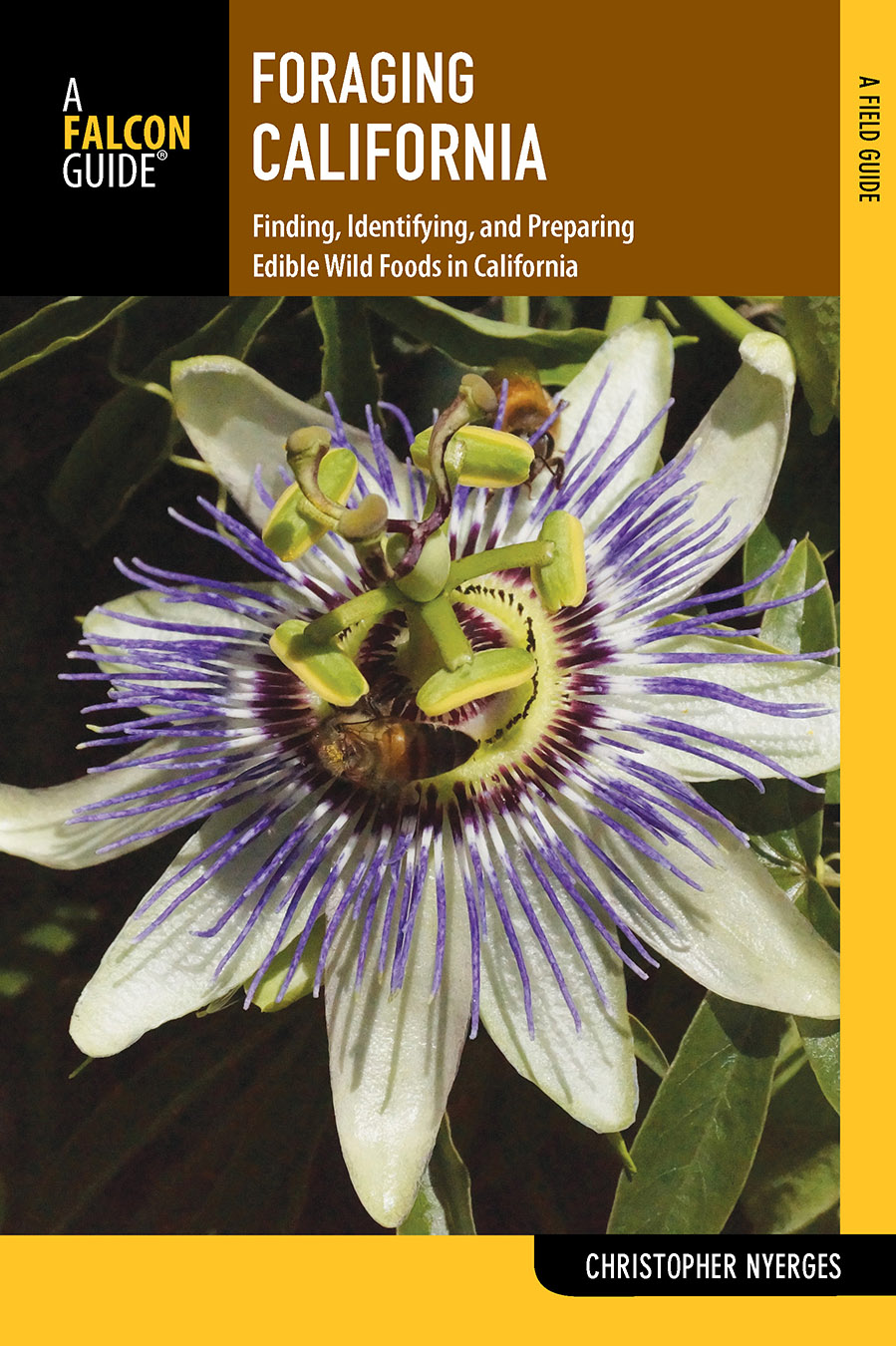

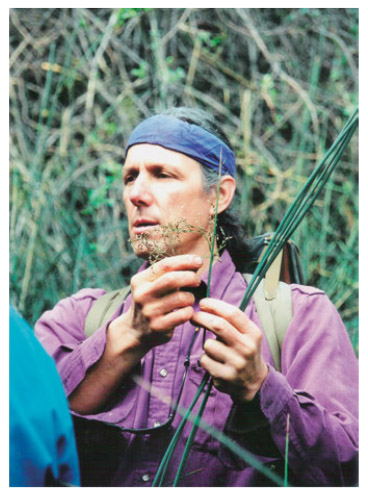

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Christopher Nyerges, cofounder of the School of Self-Reliance, has led wild-food walks for thousands of students since 1974. He has authored ten books on wild foods, survival, and self-reliance, and thousands of newspaper and magazine articles. He continues to teach where he lives in Los Angeles County, California. More information about his classes and seminars is available at www.SchoolofSelf-Reliance.com, on Facebook, or by writing to School of Self-Reliance, Box 41834, Eagle Rock, CA 90041.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

After I had already spent several years learning botany and ethnobotany in high school and college, books and lectures, often very piecemeal and second-hand, I had the very good fortune in approximately 1974 to meet Dr. Leonid Enari, the senior biologist at the Los Angeles County Arboretum, who was teaching his course on Edible, Medicinal, and Poisonous Plants. His knowledge was astronomical, and after I took several of his courses, he always allowed me to come to his office where he would identify the various plants I brought him and tell me their stories. Never once did I bring him a plant that he didnt know. In most cases, he knew several stories about each plant. He eagerly worked with me on my first book, and he assisted me in compiling lists of safe and primarily edible plant families. His unique background in botany and chemistry made him ideally suited as a primary source of information. He acted as my teacher, mentor, and friend, and he always encouraged my study and teaching in this field. I felt the great loss when he passed away in 2006 at age eighty-nine. Thus, it is to Dr. Enari that I dedicate this book, Foraging California.

I also had many other mentors, teachers, and supporters along the way. These include (but are not limited to) Dr. Luis Wheeler (University of Southern California botanist), Richard Barmakian (nutritionist), Dorothy Poole (Gabrielino chaparral granny), Richard E. White (founder of the nonprofit WTI, who taught me how to teach, and how to think), John Watkins (a Mensan who knew everything), Mr. Muir (my botany teacher at John Muir High School), Robert Tally of the Los Angeles Mycological Association, William Breen (also of the LA Mycological Association, who taught me to cook with mushrooms), and Pascal Baudar and Mia Wasilevich, both wild-food cooking experts. These individuals all imparted valuable information to me, and they have all been my mentors to varying degrees; I also thank them for their influence. Euell Gibbons also had a strong impact on my early studies of wild food, mostly through his books; I met him only once.

Of course, there have been many others who taught me bits and pieces along the way, and I feel gratitude for everyone whose love of the multifaceted art of ethnobotany has touched me in some way. Some of these friends and strong supporters have included Peter Gail, Gary Gonzales, Dude McLean, Alan Halcon, Paul Campbell, Rick and Karen Adams,Barbara Kolander, Jim Robertson, and Timothy Snider. I also want to extend a special thanks to my beloved wife, Helen, for her support of this project, and for putting up with me all this time!

Christopher with Euell Gibbons in 1975

Yes, I took many of the photos in this book, but I couldnt do it all myself. Rick Adams deserves special thanks for the many trips we took together to get many of the photos for this book. Other folks who contributed photos include my wife, Helen; Gary Gonzales; Barbara Kolander; Otto Gasser; Vickie Shufer; Louis-M. Landry; and Jeff Martin.

Photographer Rick Adams

ARE WILD FOODS NUTRITIOUS?

It is a common misconception that wild foods are neither nutritious nor tasty. Both these points are erroneous, as anyone who has actually taken the time to identify and use wild foods can testify. Ive also had many new students who had been convinced about the nutritional value of wild foods but assumed that the plants nevertheless tasted bad. Of course, a bad cook can make even the best foods unpalatable. And if you pick wild foods and dont clean them, dont use just the tender sections, and dont prepare them carefully, then certainly you can turn someone off to wild foods.

My friends Pascal Baudar and Mia Wasilevich continue to use wild foods in their gourmet dishes and classes, and they have proven that wild foods are not only nutritious but can be as flavorful as any foods in the finest restaurants.

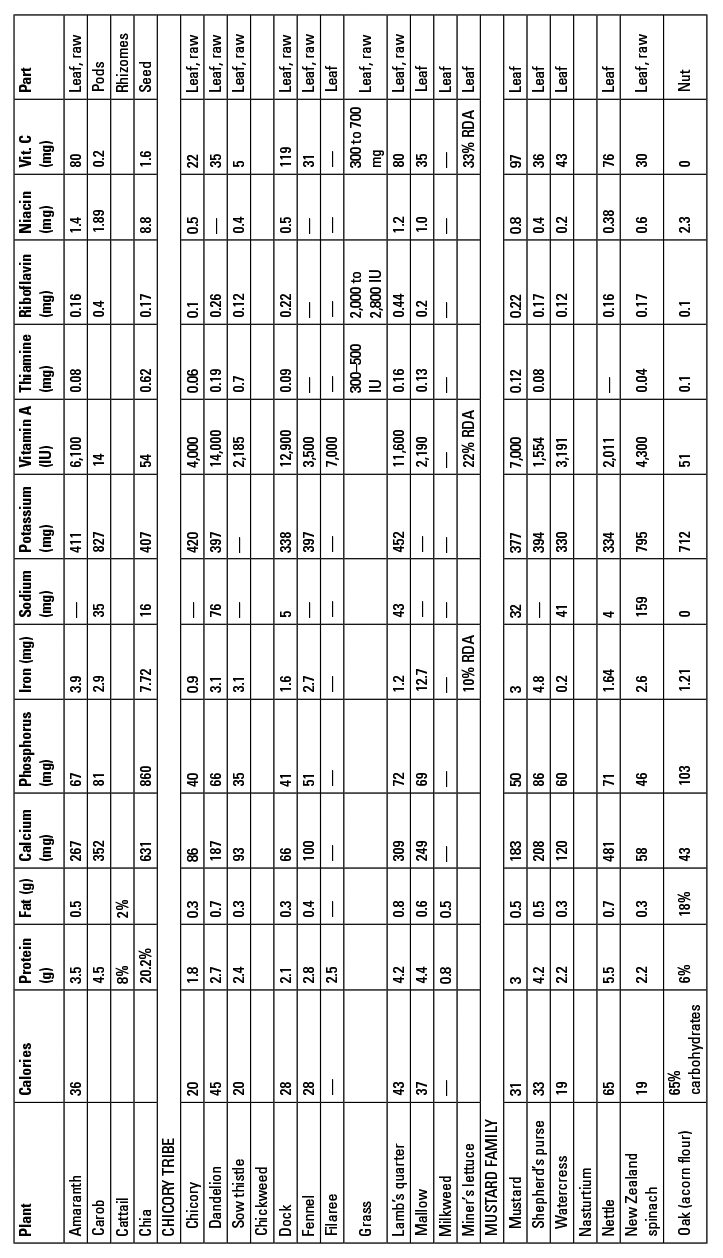

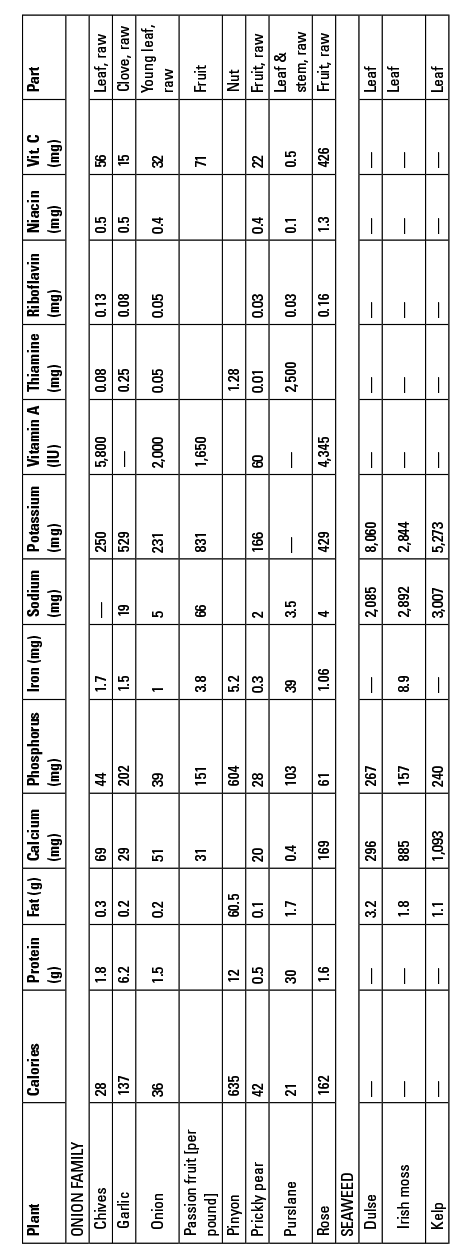

For your edification, here is a chart extracted from Composition of Foods, US Department of Agriculture, to give you an idea of the nutritional content of the common wild foods.

Nutritional Composition of Wild Foods

The data below are per 100 grams, unless otherwise indicated. Blanks denote no data available; dashes denote lack of data for a constituent believed to be present in measurable amounts. Only a select number of plants for which we had data are represented.

Seaweeds

Christopher with a section of kelp. RICK ADAMS

MARINE GREEN ALGAE

Chlorophyta (About 5,000 species, including sea lettuce)

BROWN ALGAE

Phaeophyta (Approximately 1,000 species, including all kelps, rockweed, etc.)

RED ALGAE

Rhodophyta (The most abundant seaweed of the world, with over 4,000 species, including Irish moss, dulse, laver, etc.)

Use: Food (depending on species, some are eaten dried, cooked, raw, or pickled), nutrition, utility

Range: Restricted to the ocean

Similarity to toxic species: See Cautions

Best time: Available year-round

Status: Relatively common

Tools needed: Bucket, gloves

Properties

Most people know seaweeds when they see them at the beach, floating in the surf, lying on the beach. They grow in a large array of colors, sizes, and shapes. The kelps are perhaps the most conspicuous along the California coast, with their long stipes and characteristic fronds. They often lie in masses on the beach. And the farther north one goes, the greater the diversity.

In general, the seaweeds have leaflike fronds, stipes that resemble the stems of terrestrial plants, and holdfasts that resemble roots. Some seaweeds are very delicate, and others are very tough and almost leathery. Many have hollow sectionsfloatsthat allow them to float more readily.

Others are like thin sheets of wet plastic, such as the sea lettuce. Their colors generally indicate their category of green, brown, or red marine algae.