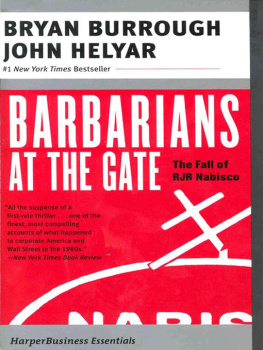

BARBARIANS

AT THE GATE

The Fall of RJR Nabisco

Bryan Burrough AND John Helyar

HarperBusiness Essentials

To my wife, Marla Dorfman Burrough,

and to my parents, John and Mary Burrough

of Temple, Texas JBB

To my wife, Betsy Morris,

and to my parents, Richard and Margaret Helyar

of Brattleboro, Vermont JSH

The officer of every corporation should feel in his heartin his very soulthat he is responsible, not merely to make dividends for the stockholders of his company, but to enhance the general prosperity and the moral sentiment of the United States.

ADOLPHUS GREEN, founder, Nabisco

Some genius invented the Oreo. Were just living off the inheritance.

F. ROSS JOHNSON, president, RJR Nabisco

This business, on a legitimate basis, is a fraud.

Not that its a fraud. You need money to be in this business. But not a lot. You need more money to open a shoe-shine shop than you do to buy a $2 billion company, lets be honest about it. But to buy a shoe-shine store, if it costs $3,000, you need $3,000. If you dont got it in cash, you need to bring it by Thursday.

But if its an LBO, not only do you not have to bring it, you dont have to see it, you dont know where youre going to get it, nobody knows where they got it from. The whole situation comes from absolutely nothing.

But the more you need, of course, the less money you need. In other words, if theres money involved, you dont get involved in this business. This is a business for people who dont have money, but who know somebody who has money, but who doesnt put it up either

JACKIE MASON, What the Hell is an LBO?

This book arose from the authors coverage in The Wall Street Journal of the fight to control RJR Nabisco in October and November 1988. Our goal in pursuing the story behind those public events has been to meet the standard of accuracy and general excellence that the Journal sets for journalists everywhere.

Ninety-five percent of the material in these pages was taken from more than 100 interviews conducted between January and October 1989 in New York, Atlanta, Washington, Winston-Salem, Connecticut, and Florida. In large part due to contacts we made while working at the Journal, we were able to interview at length every major figure involved in the story as well as scores of minor ones. No more than a handful of people mentioned in this book declined to grant interviews.

Among the first we spoke with were the long-shot suitors, Jim Maher of First Boston and Ted Forstmann of Forstmann Little & Co., who made himself available in his New York office as well as on his private jet. At Kohlberg Kravis, Henry Kravis, George Roberts, and Paul Raether were interviewed together and separately for more than twenty hours; much of the interviewing was done in RJR Nabiscos former New York offices, where Kohlberg Kravis briefly relocated after a fire. Kravis himself sat for a half-dozen tape-recorded sessions, all but one in Johnsons former anteroom.

The last to consent to be interviewed was Ross Johnson. He was understandably gun-shy; he had taken a beating in the press and wasnt eager for further pummeling. Eventually he spent thirty-six hours in one-to-one talks with the authors. Several all-day sessions were held in his Atlanta office, where Johnson smoked cigarillos and wore sports jackets with no tie; a marathon evening session was held in his New York apartment, where Johnson donned a pair of gray RJR Nabisco sweatpants and shared pepperoni pizza and beer with the authors.

Due to the cooperation of the participants, we have managed to reconstruct dialogue extensively. By necessity this involves calling on sometimes selective memories. It is important to remember that, as Ken Auletta wrote in his definitive Greed and Glory on Wall Street, no reporter can with 100 percent accuracy re-create events that occurred some time before. Memories play tricks on participants, the more so when the outcome has become clear. A reporter tries to guard against inaccuracies by checking with a variety of sources, but it is useful for a readerand an authorto be humbled by this journalistic limitation.

We couldnt agree more. However, it should be noted that, in reconstructing critical meetings, we often were able to interview every person in the room at the time. In many cases, that amounted to as many as eight or nine people. Where their memories have differed significantly, it is noted in the text or a footnote. Where a thought or impression is conveyed in italics, it was supplied by the person in question.

A word about significance: Those looking in these pages for a definitive judgment on the impact of leveraged buyouts on the American economy will no doubt be disappointed. It is the authors contention that some companies are well suited for the rigors of an LBO, while others are not. As for RJR Nabisco, it is important to remember that an LBO is a creature of time. In most cases its success or failure cant be determined for three, four, five, even seven years. The events in this book constitute the birth of an LBO; at this writing, the reborn RJR Nabisco is barely a year old. The baby looks healthy, but its too soon to predict its ultimate fate.

We would like to thank Norman Pearlstine, The Wall Street Journal s managing editor, who gave his blessings for a leave to do this book. We are immensely grateful to our editor, Richard Kot of Harper & Row, for his keen eye and unflagging encouragement in helping us negotiate our first journey into publishing; his assistant, Scott Terranella; Lorraine Shanley, who brought our project to Harper & Rows attention; our agent, Andrew Wylie, who isnt nearly as nasty as people think; his colleague, Deborah Karl, for plenty of on-call hand-holding; and Steve Swartz of The Wall Street Journal, who provided invaluable advice on shaping the narrative. RJR Nabisco and numerous players in the RJR drama were helpful in supplying photos. Thanks are also due John Huey who, as The Wall Street Journal s Atlanta bureau chief in 1988, gave John Helyar rein to delve into RJR. As editor of Southpoint magazine in 1989, he allowed him to finish this book before reporting for duty.

The unsung heroes of a project like this are our wives. Betsy Morris served double duty. As a Wall Street Journal colleague, she was among the first to discover Ross Johnson and chronicle the emerging RJR Nabisco story. As John Helyars wife, she put up with long weeks absences and long days writing. Likewise, Marla Burrough was the manuscripts first reader, copy editor, and a source of unlimited support and patience. Their advice and guidance are marked on every page of this book.

Bryan Burrough

John Helyar

October 1989

The Management Group

At RJR Nabisco

F. Ross Johnson, president and chief executive

Edward A. Horrigan, Jr., chairman, RJR Tobacco

Edward J. Robinson, chief financial officer

Harold Henderson, general counsel

James Welch, chairman, Nabisco Brands

John Martin, executive vice president

Andrew G. C. Sage II, consultant and board member

Frank A. Benevento II, consultant

Steven Goldstone, of counsel

George R. (Gar) Bason, Jr., of counsel

At American Express

James D. Robinson III, chairman and chief executive

At Shearson Lehman Hutton

Peter A. Cohen, chairman and chief executive

J. Tomilson Hill III, merger chief