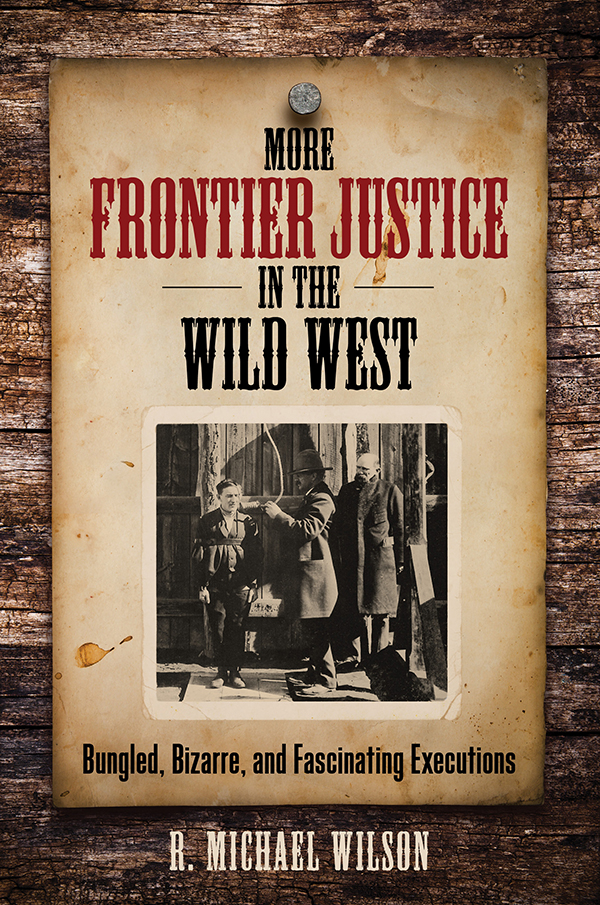

R. Michael Wilson

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2014 by R. Michael Wilson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

TwoDot is a registered trademark of Rowman & Littlefield

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-0-7627-9602-1 (paperback)

eISBN 978-1-4930-1550-4 (eBook)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Contents

Introduction

The administration of justice on Americas western frontier was relatively consistent. Even when citizens resorted to vigilante action, a sentence of death was usually restricted to situations where a premeditated, cold-blooded murder had been proven, or at least proven to the majority of the mob. There were a few exceptions among extralegal executions, and many lynchings went unreported or unconfirmed, but among the numerous legal executions occurring before the end of 1911 there was only one man hanged for a crime other than first-degree murder: Thomas Ketchum. He was hanged in Clayton County, New Mexico, for assaulting a train, and his execution was among several of the most bungled affairs in the annals of the Old West. However, the decapitation of Thomas Ketchum was not the only bungled execution in the West.

Pablita Sandoval, one of only two women executed on the western frontier, met Miguel Martin when she was twenty-six years old, and a torrid affair followed. Martin, husband and father of five, soon tired of the relationship with his mistress and informed her that he wanted to end things, but Sandoval convinced Martin to see her one last time. On March 23, 1861, they met; Sandoval hugged her lover for the last time, and while Martin was distracted, she pulled a butcher knife from the folds of her dress and stabbed him to death. Sandoval was arrested, held over for trial, convicted of murder in the first degree, and sentenced to hang. Sheriff Antonio Herrera selected for the gallows a cottonwood tree within one mile of the Church of Las Vegas, New Mexico. At 10:00 a.m. on April 26, 1861, Sandoval was placed in a wagon, where she sat upon her coffin. Sheriff Herrera drove the wagon directly beneath the limb, ordered Sandoval to stand, and hurriedly adjusted the noose before he jumped onto the wagon seat and whipped up the horses. The wagon lurched forward from beneath Sandovals feet before the sheriff realized he had not bound the condemned womans wrists and ankles. Sandoval was strangling while struggling to pull herself up, so the sheriff used all his weight to pull down on her legs. Outraged spectators rushed in, pushed the sheriff away, and cut down Sandoval. Colonel J. D. Serna then read the death warrant, which stated clearly that Sandoval was to be hanged until dead. The sheriff backed the team and wagon under the limb, tied a new noose in the rope, lifted Sandoval into the wagon bed and put the noose around her neck, and pinioned her wrists and ankles. He took but a moment to examine his work before driving the wagon out a second time, and the law was satisfied.

New Mexico, it seems, was the worst place to be executed. When William Wilson was hanged on December 10, 1875, he had the benefit of a gallows and a carefully calculated drop, but it did not improve his chances for a merciful death. The lever was kicked, the trapdoor sprung, and Wilson fell, but his neck was not broken. After nine and one-half minutes of strangling, the body went limp and then he was cut down without a doctors examination. His remains were placed in a coffin, and the black hood was removed. Spectators were allowed to file past to have one last look at the murderer when one curious Mexican woman, making a careful examination of the body, suddenly cried out For Gods sake, the dead has come to life. Wilson was then examined by the attending physician and found to be alive. A rope was quickly tossed over the crossbeam of the scaffold, an impromptu noose was tied around Wilsons neck, and several men from the crowd pulled the condemned man right up out of his coffin. He hanged another twenty minutes until strangulation finally completed the task required by law.

Hanging remained the most common form of execution on the western frontier, and there were two basic forms of gallows. The most common scaffold was built with a platform about eight feet above the ground and the condemned man was dropped through a trapdoor. In about a quarter of the executions, the gallows was a platform at ground level and the rope was attached to a great weight suspended above the ground which, when dropped, jerked the man upward, breaking his neck. There are no recorded decapitations using a twitch-up gallows, but on December 27, 1889, Nah-diez-az, a very lightweight Pinal Indian, was jerked up so forcefully by a 340-pound copper ingot that his skull was crushed on the crossbeam. In Colorado this latter form of gallows was improved almost to perfection. It was called the automatic suicide machine, because the weight of the condemned man on the platform activated the release. The act of springing the trap or dropping the weight was particularly disagreeable, so other means of doing so were adopted. Perhaps the most famous was the water lever release system used in Wyoming to hang teenager Charles Miller on April 22, 1892, and Tom Horn on November 20, 1903. Time and experience did not seem to improve hangings, and on November 10, 1916, Lucius Hightower was decapitated by a trapdoor gallows. In June 1890, in Nevada, Elizabeth Potts narrowly escaped beheading by the skin of her neck, but on February 21, 1930, Eva Dugan was decapitated in Arizona, and the outrage led to a legislative change to the use of the gas chamber.

A hanged man usually remained suspended until an attending physician pronounced him dead. The time varied with each individual, but one scientist who argued for electrocution as a substitute for hanging stated that, a man is usually sixteen minutes dying at the end of a hangmans rope. In fact, every hanging was unique, and Dr. D. S. Lamb, an ex-surgeon of the United States Army, studied the subject and in 1894 reported in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat:

DEATH BY HANGING

The Three Different Stages Through Which the Victim Passes

I have made the subject of death by hanging a long study. From my observations during my experience in the army I feel justified in saying that death by hanging is the most exaggerated of all modes. It may be immediate and without symptoms but the subject must pass through three stages before death.

In the first stage the victim passes into a partial stupor lasting from thirty seconds to two minutes, but this is generally governed by the length of the drop, the weight of the body, and the tightness of the constriction. There is absolutely no pain in this stage; the feeling is rather one of pleasure. The subjective symptoms described are intense heat in the head, brilliant flashes of light in the eyes, deafening sounds in the ears and a heavy numb feeling in the lungs. In the second stage the subject passes into unconsciousness and convulsions usually occur. In the third stage all is quiet except the beating of the heart. Just before death the agitation is renewed, but in a different way from that in the second state. The feet are raised, the tongue has a peculiar spasm, the chest heaves, the eyes protrude from the orbits and oscillate from side to side, and the pupils dilate. The pulse can, in most cases, be felt ten minutes after the drop.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.