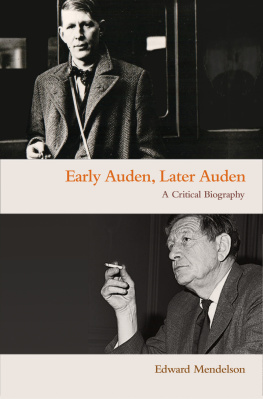

This is the first account of Audens life to make use of the large number of his letters and other manuscripts which are now accessible, and, though the book is not an authorised biography and was undertaken on my own initiative and not at the request of Audens executors, I am very grateful to his Estate for permission to quote from these previously unpublished writings.

It is not a book of literary criticism. I have not usually engaged in a critical discussion of Audens writings. But I have tried to show how they often arose from the circumstances of his life, and I have also attempted to identify the themes and ideas that concerned him. I hope I have also managed to convey my own huge enthusiasm for his poetry.

H. C.

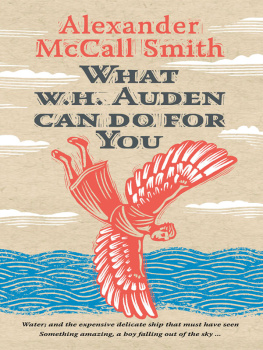

Biographies of writers, declared W. H. Auden, are always superfluous and usually in bad taste. A writer is a maker, not a man of action. To be sure, some, in a sense all, of his works are transmutations of his personal experiences, but no knowledge of the raw ingredients will explain the peculiar flavour of the verbal dishes he invites the public to taste: his private life is, or should be, of no concern to anybody except himself, his family and his friends.

Auden wrote this towards the end of his life, but it was an opinion that he had held for many years. He even suggested that most writers would prefer their work to be published anonymously, so that the reader would have to concentrate on the writing itself and not at all on the writer. He was also (he said) opposed in principle to the publication of, or quotation from, a writers letters after his death, which he declared was just as dishonourable as reading someones private correspondence while he was out of the room. As to literary biographers, he branded them as, in the mass, gossip-writers and voyeurs calling themselves scholars.

So it scarcely came as a surprise when, after his death in September 1973, his executors published his request that his friends should burn any of his letters that they might have kept, when they had done with them, and should on no account show them to anyone else. Auden himself had explained, in a conversation with one of his executors not long before his death, that this was in order to make a biography impossible.

In the months that followed Audens death, a very few of his friends did burn one or two of his letters. But most preserved what they had, and several people gave or sold letters to public collections. Meanwhile many of his friends, far from doing anything to hinder the writing of a life, published (in various books and journals) their own memoirs of him, which provided valuable material upon which a biographer could work.

At first sight it may seem as if they were riding roughshod over Audens last wishes. But it is not as simple as that. Here, as so often in his life, Auden adopted a dogmatic attitude which did not reflect the full range of his opinions, and which he sometimes flatly contradicted.

Certainly he often attacked the principle of literary biography, but in practice he made a lot of exceptions. When reviewing actual examples of the genre he was almost always enthusiastic, finding a whole variety of reasons for waiving his rule. We need a biography of Pope, he said, because so many of Popes poems grew from specific events which need explaining; we want a life of Trollope because his autobiography leaves out a great deal; of Wagner because he was a monster; of Gerard Manley Hopkins because he had a romantically difficult relationship with his art. Audens no biography rule was in other words (as his literary executor Edward Mendelson has put it) flexible enough to be bent backwards.

The same is true of his attitude to writers letters. He usually reviewed published collections of them in friendly terms, and was only censorious when he thought that something private had been included which was merely personal and threw no light on the writers work. He himself made a selection of Van Goghs letters for publication, and he would have published an edition of the letters of Sydney Smith if someone else had not done it first. As to his own letters, he gave permission for a large number of quotations from them to be published, in academic books and the like, during his lifetime.

He also left a great deal of autobiographical writing. He once declared: No poet should ever write an autobiography; yet he did a great deal towards preserving a record of his own life. Not only does his poetry contain innumerable autobiographical passages, but several poems (including two of his longest, Letter to Lord Byron and New Year Letter) are largely autobiographical in character. Among his prose writings, too, there are all kinds of remarks about events in his life. And in his later years he allowed journalists to visit him in his New York apartment and at his summer house in Austria, letting them publish interviews with him which often recorded highly personal details of his life.

So there is a great deal of information for a biographer to draw upon. But would Auden, in the end, have approved of a biography being written?

It is possible that he might on the grounds that he was something of a man of action, who lived a life so full of interest that it deserves to be recorded for its own sake. This was a justification of biography that he accepted with one proviso. The biography of an artist, if his life as a man was sufficiently interesting, is permissible, he wrote, provided that the biographer and his readers realise that such an account throws no light whatsoever upon the artists work.

This last point, of course, brings us back to Audens fundamental objection to a writers biography. I do believe, however, he once added, that, more often than most people realise, his works may throw light upon his life.

Wystan Hugh Auden was born on the twenty-first of February 1907, in the city of York in the north of England, the third and last child of George Augustus Auden and Constance Rosalie Bicknell.

He was the youngest of three boys. Later in his life he liked to point out that in fairy-tales it is the youngest of the three brothers who succeeds in the quest and wins the prize. I, after all, am the Fortunate One, he wrote in a poem, The Happy-Go-Lucky, the spoilt Third Son.

He had hazel eyes, and hair and eyebrows so fair that they looked bleached. His skin, too, was very pale, almost white. His face was marked by one small peculiarity, a brown mole on the right cheek. He had big chubby hands, and soon developed flat feet. He was physically clumsy, and took to biting his nails.

The fairness of hair and skin were inherited from his father, but in features he looked more like his mother. From the time of his birth he was very close to her, partly because being the youngest child he was never displaced by another, partly, too, because there was a gap of several years between himself and his elder brothers, so that they tended to go off by themselves and leave him with their mother. (This large gap was the consequence of a miscarriage between the second and third births.) But his closeness to his mother was, he himself came to believe, chiefly the result of her wanting it to be that way. He felt that she had sought to achieve with him, from the beginning, a conscious spiritual, in a sense, adult relationship.

Besides being the youngest child he was also the youngest grandchild in the family; and later at school, being a bright boy, he was very often the youngest in the class. All this gave him, he said, the lifelong conviction that in any company I am the youngest person present. Certainly to the end of his life he behaved like a precocious and highly praised youngest child.