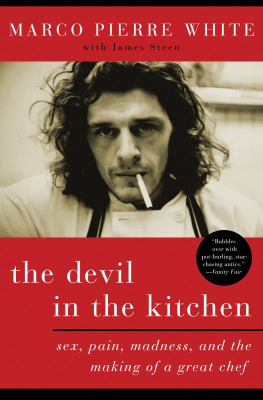

THE DEVIL

in the

KITCHEN

SEX, PAIN, MADNESS, AND THE

MAKING OF A GREAT CHEF

MARCO PIERRE WHITE

with JAMES STEEN

BLOOMSBURY

Contents

C ANT STAND FLYING. Hate it.

The fear stems from my inability to understand how planes stay in the sky and the knowledge that some of them dont. I have agreed to attend business meetings abroad, and then cried off because I couldnt bring myself to board the plane. I surprised even myself when I agreed to come to the U.S. for a book tour in May 2007. This wouldnt be a simple return trip from my comfort zone in London to New York. The eighteen-page itinerary had me flying all over the place, from San Francisco to Miami and lots of places in between. During the first three days of the seventeen-day trip Id managed nine hours of sleep and had turned into an exhausted, jet-lagged beast, stumbling from book signing to radio show to airport, being overfed and plied with too much alcohol along the way.

I dont want to sound like a moaning British gitthere are far worse things than being given too much food and drink and staying in nice hotels. What I should point outand this is importantis that I fell in love with America. Its an extraordinary place. When it comes to food and gastronomy, it reminds me of my early days in the industry (Britain back in the 1970s and early 80s), when people still got excited about Michelin, and chefs wanted to be great cooks and win awards, rather than become famous. The restaurant scene in the United States is just more exciting than in the UK, where Michelin-starred restaurants are patronizing to customers and the staff dictates how you should eat your food, all the while reminding you that youre lucky to have even gotten a table. I didnt get any of that in the States. The dining experience in America is much more democratic.

In Chicago, I enjoyed both the technical brilliance of a ten-course meal by Grant Achatz at Alinea and the most delicious hot dog of my life at Hot Dougs, where I waited in a queue for twenty minutes just to get inside.

In New York, I was reunited with my old friend Mario Batali, the celebrated chef with whom I worked at the Six Bells, in Chelsea, London, in the mid-eighties. Up until then, the last time hed seen me was just as I was chucking a pan of hot risotto in his direction. Hes since forgiven me.

Mario met me at my hotel and said he would take me on a quick sightseeing tour on the way to lunch at one of his restaurants. We stepped out of the hotel, and he handed me a motorbike helmetno visor, no strapand said, Put that on. Lets go. He then pointed at a parked Vespa to which I said, Mario, its great to see you after all these years, but theres no way the two of us are going to fit on that thing. Hes a big man, and Im not small, either. Marco, put the helmet on, he said. Somehow we managed to squeeze onto the saddle and we zoomed off.

I found myself on the back of that Vespa for a good portion of my stay in New York, stopping to enjoying tripe and spaghetti with bottarga at Marios legendary restaurant Babbo; marveling at the live frogs, eels and fish in Chinatown; taking in the view of the citys skyline from the Brooklyn side (note to the reader: the view is better enjoyed when one isnt jet-lagged, stuffed to the gills with food and wine and suffering from the onset of hypothermia); and, of course, teaching the good people of New York City about a drink I call the house cocktail. The house cocktail consists of a large shot of sambuca, which you set on fire before slamming your hand down onto the glass. The aim is to get the glass to stick to your palm, and then suck the air and sambuca out of it in one quick shot. Halfway through one of my tutorials, someone knocked the flaming drink onto me, shattering the glass and causing shards to bury themselves in my hand. All in a days work.

Its been quite a year. In addition to discovering America, one of the biggest changes in my life has been my decision to step back into the kitchen for the first time since 1999. A few weeks after the publication of the hardcover edition of this book, I received two offers of work, which, if accepted, would mean that I would have to put on the apron again and return to the kitchen.

I accepted both invitations.

The first job seemed uncomplicated enough and, given my experience, undemanding. I was asked if I would go to France to do a cooking demonstration for fifteen ladies in the kitchens of Sir Rocco Fortes hotel, Chateau de Bagnols, which is just outside Lyon. The women were all guests at the hotel. Their husbands would be spending the day wine-tasting at the Montrachet vineyard, while I would be at the stove doing my demonstration. When I arrived at the hotel, a smartly dressed man dashed up to me, held out his hand for a shake and said, Hello, Darko.

I was a bit irritated that he couldnt get my name right and said, No, its Marco.

Again he said, Hello, Darko.

Again I said, No, its Marco. Its Marco with an M.

No, he said, Im Darko, Marco. Im the host. I felt a bit of an idiot (and after that I was very polite to Darko), but not half as stupid as I did the following day, when it was time to do the demo.

The plan was to cook three dishes in one hour, or rather, rustle up three dishes that each took a mere twenty minutes to make. These dishes had to be quite effortless and easy to cook at home. I decided to serve grilled lobster with parsley and chervil and a bearnaise mousse-line; turbot with citrus fruits, a little coriander and some fennel; then sea bass la nioise. It was while cooking the last onethe sea bass dishthat I came unstuck... or rather stuck to a plate.

Sea bass la nioise is a simple dish in which the tomatoes are put under the grill so that the water content evaporates under the heat. Youre getting rid of the acidity, basically, and bringing out the sweetness. Once grilled, the tomatoes are thrown into a pan that contains olive oil, lemon juice, coriander and basil. During the grilling process, I somehow got dragged into a bit of chitchat with the ladies, which was disastrous because the distraction caused me to lose my timing. There I was, bantering, laughing and cracking jokes, when suddenly I remembered the plate of tomatoes under the grill. As I grabbed the plate, I felt the most excruciating pain in my hand and realized that the searing heat of the dish had welded my thumb to the porcelain. My entire body must have flinched. Yet the gaggle of smiling ladiesmy happy pupilsdidnt seem to notice that their cookery teacher was being cooked.

I told myself I had two options: first, I could either be professional and pretend nothing was happening, even though I could not remember the last time I had had so much pain inflicted upon me; second, I could succumb to the agony, cave in, drop the plate and scream so loud and for so long that I would shake the foundations of Roccos chateau.

I went for the first option. In my head there was this mantra: takethe pain, take the pain, just take the bleeding pain. I must tell you, that plate came out of the grill faster than any plate has ever come out of a grill. Normally, I would have got a spoon and scraped the tomatoes from the plate and into the pan, but because of the agony I was enduring there wasnt time for the spoon. I found myself tossing the sliced tomatoes from the hot plate into air, and it just so happened that they landed neatly in the pan, on top of the herbs, the olive oil and lemon juice. It looked like a circus trick. Afterwards the kitchen chef came up to me and said, Wow, you are so quick. I should have said to him, It helps if youre handling a plate that feels like molten lava. But I didnt.

While learning how to live with a grilled thumb back in London, I got my second offer to return to the kitchen. It was a call from the

Next page