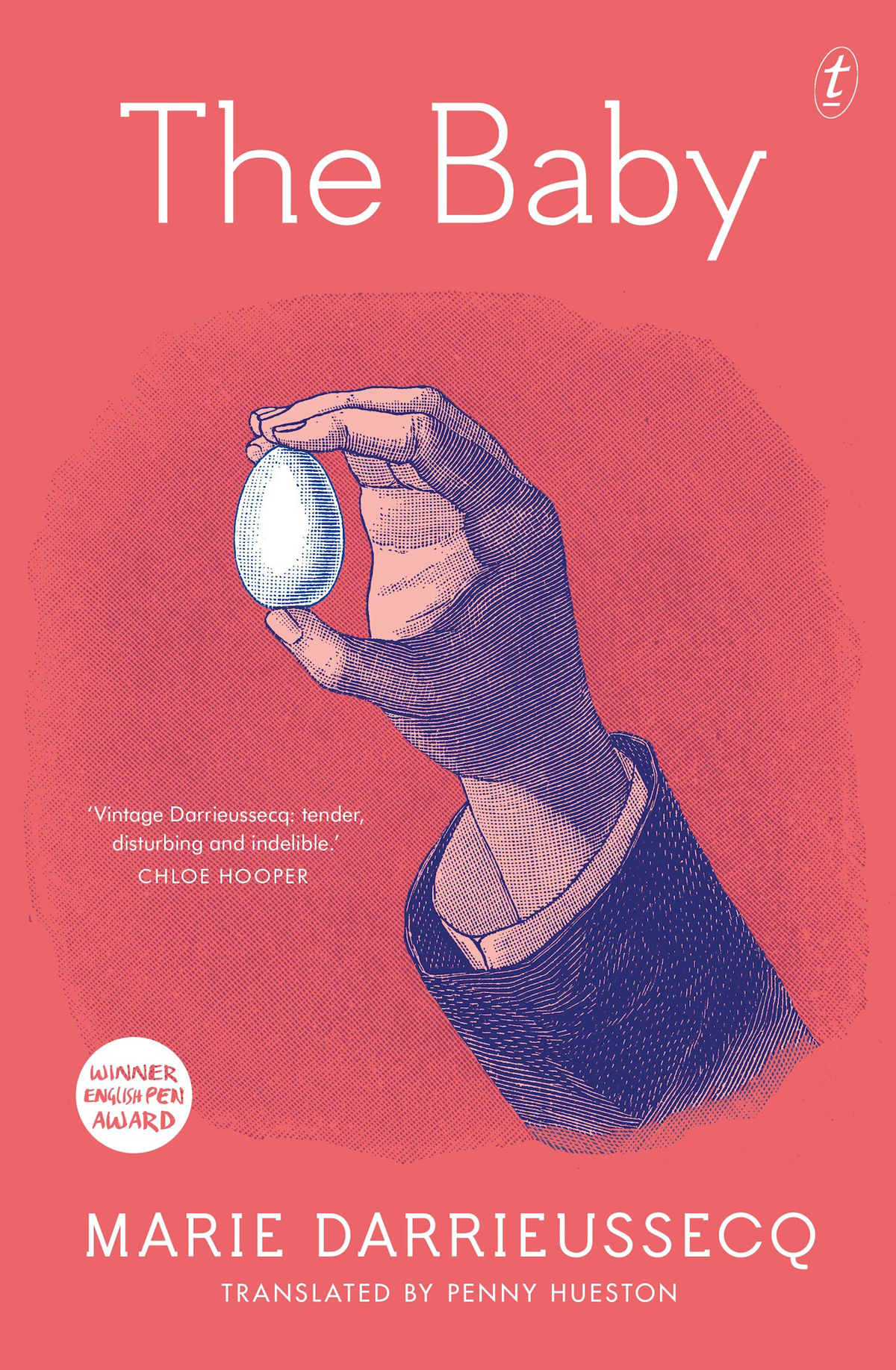

The Baby is a mothers project and a writers projecthow to reconcile these two demanding roles? What is a baby? And why are there so few of them in literature? Through notes taken in the months after her first child was born, Darrieussecq, in her characteristically ingenious style, makes observations that will bring smiles and grimaces of recognition, and raise important questions.

Along with the banal drudgery of childcare, there is the euphoria, the obsession, the terror and the visceral focus on the body. Arguing with Saint de Beauvoir, Darrieussecq examines how women as mothers are targeted from all angles. How, she asks, can a woman be more and other than a mother?

Give me children, or Ill die.

Genesis

Those little feet, wriggling. They used to bump inside my belly.

I cannot believe that he came out of me.

One day a delivery man rang my doorbell, I had a big belly, in the package there was a baby, and I didnt have a big belly anymore.

A baby human being: there must be something to investigate, to understand here.

It is a repetitive and fragmented experience. When the baby sleeps life starts up again, but when hes awake its his life that dominates everything.

I had little to go on in those strange days at the beginning; perhaps because thats when an exclusive intimacy develops, the connection, the suffocation, the dizzy feelingtime divided into approximately six intervals, neither day nor night, an hour or two for breastfeeding, nappy-changing, putting back to sleep, an hour or two of sleep, and then it starts all over again.

I stopped despairing when I realised that this period of time would be short, that it wouldnt last a lifetime. I stopped despairing when a crche materialised. They could take him in October. Time organised itself around that date: when I would join the outside world again. So I sank into that milk bath, I floated, sloshed around in it, I got drunk on this baby time, because later I would begin to think again, to write, to live in the company of men.

Write while hes asleep.

My best friend, pregnant, presented her deductive reasoning: Entitlement to childcare does not exist, therefore women are not entitled to work.

Hes moving about in his sleep, and immediately I get up, my notebook open, and I lean overthat movementlike a willow, like a rower: his existence is astonishing; it is incomprehensible.

Looking at photos of us, new mothers, my best friend and me: they are photos of our mothers.

The hospital bed, the weariness in our faces, the light.

It is incomprehensible.

It wasnt that I didnt like babies; they just didnt exist. There was no bond, no relationship at all between them and me. A childI was happy enough to have one, one day. The word baby, bland and superfluous, disqualified everything that related to it; the topic was of no interest to me.

These days, I appreciate that people are not interested in him, in the baby, but that indifference seems phoney; its not serious. My German translator called me soon after the birth. I had received congratulationssoft toys, teddy bears and rabbits, hearts and ribbonsfrom people in several countries. But this particular translator, despite my hints, only wanted to talk work.

I found his behaviour comical, a little bit deranged.

During this period, it was the obstinacy of certain people that I clung to for my mental equilibrium.

The baby stops me from writing by waking up.

In A Frozen Woman, Annie Ernaux writes: For two years, in the prime of my life, every bit of my freedom was reduced to the anxiety around a childs afternoon nap.

The baby stops me from smoking and drinking, because Im breastfeeding.

I smoke and drink on the sly, like some alcoholics do.

In order to prolong the writing of this page by a few minutes, Ive turned him on his belly: he slips back into a deep sleep. These days, doctors advise against this position: it can cause Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

Before, babies were mainly bodies, noisy, dirty, dribbling, rarely attractive. I preferred the babies of animals: kittens, lion cubs, cute little creatures.

When the baby was born, I shared this preference with the man who, oddly enough, had become the babys father. He reproached me so coldly that I changed my opinion at once: now I prefer babies.

The baby lies on my knees now when I watch animal documentaries on television. He watches the moving light.

What does he see?

Given everything you hear about babies, I thought he was autistic, because he didnt focus his gaze.

My best friend thought her baby had Down syndrome because he stuck out his tongue.

A friend who worked in Goma, in the Congolese camp, told me that the infant mortality rate there is sixty per cent.

The baby has made me sentimental; hes taken me back to sentimentality. I wonder what to do with this old vocabulary.

To say the unsaid: that is the intention of this writing. Halfway between saying and not saying are clichs that reveal, despite their wear and tear, a portion of reality. The baby allows me to form a kind of friendship with truisms; he makes me curious about them, gets me to pick them up like stones and examine them, to discover truths running around underneath.

I listen to the chatter in the hospital, the paediatric nurses, the other mothers, remember my own upbringing, catchphrases in magazines, the background noise of psychology: the common thread is my maternal disposition. Whats called instinct, made up of sayings and proverbs, of testimonials and advice: ancestral prattle.

I understand now why other peoples babies did not exist, because the baby only exists in an intimate continuity, in the connection with us, his parents.

We give him nicknames, secret names we delight in saying, full of double consonants, rhymes and hiccups, of hisses and hushing sounds, of milk.

When hes awake, fed, clean, when he has no pain anywhere and hes looking at us, hes already, only weeks old, a child. But after a feed, he has his nurslings face: squashed and red from the breast, smeared with drool and milk, creases in the corners of his mouth, his eyes shut like fists. The folds of my clothes have striped his cheeks; theres a track mark across his face from the zip on my cardigan. He refuses to open his eyes, so his bliss can last longer; he suckles the air, then he stretches and his body becomes hard, archedI can carry him in one handand, all of a sudden, he looks miserable, distraught.

When weve attended to him, and hes gone back to sleep, we have to do all the rest: the housework, the shopping, prepare the food, set the table, empty the dishwasher, fold the sheets. Hes not the one making us tired, its the non-stop work of running a home.

My power over him is astounding. It would be easy for me to get rid of him. I dream that I leave him behind at the supermarket, or on the beach. I find the pram, but its empty. I run away. When Im awake, between feeds, I know thats what I am forbidden to do from now on: flee, disappear, get away.

Next page