White Coats

White Coats

Three Journeys through an American Medical School

Jacqueline Marino

Photographs by Tim Harrison

The Kent State University Press

Kent, Ohio

For Stella and Charlotte

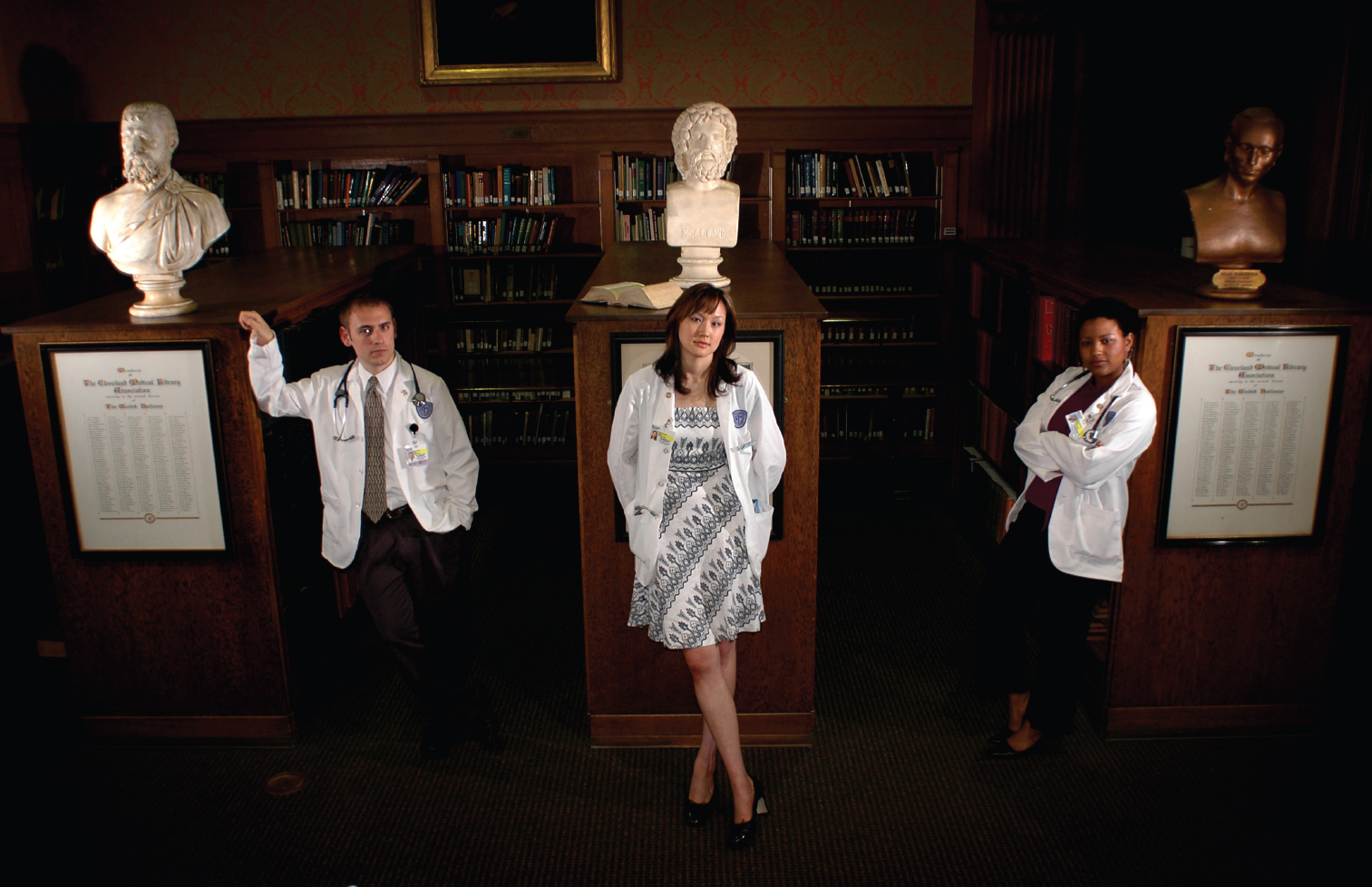

Frontis: Michael Norton, Millie Gentry, and Marleny Franco, students from the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicines class of 2009. They were photographed at the Allen Memorial Library on June 27, 2006.

2012 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2011047799

ISBN 978-1-60635-130-7

Manufactured in China

The material in this book was originally published in a substantially different form in the August and September 2006, August 2007, August 2008, and August 2009 issues of Cleveland Magazine as a feature series entitled White Coats. Permission from Cleveland Magazine is gratefully acknowledged.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Marino, Jacqueline.

White coats : three journeys through an American medical school / Jacqueline Marino; photographs by Tim Harrison.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-60635-130-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Medical studentsOhioCase studies. 2. Medical educationOhio. 3. Medical collegesOhio. 4. Case Western Reserve University. School of Medicine. I. Title.

R747.C292M37 2012

610.711771dc23 2011047799

16 15 14 13 12 5 4 3 2 1

Honor the physician with the honor due him, according to your need of him, for the Lord created him; for healing comes from the Most High, and he will receive a gift from the king. The skill of the physician lifts up his head, and in the presence of great men he is admired.

Ecclesiasticus 38:13

There is no magic moment in which the student, as an understudy to a great actor who falls ill, is thrust on to the stage. Modern medicine is too well organized for that. The transition, from young layman aspiring to be a physician to the young physician skilled in technique and sure of his part in dealing with patients in the complex setting of modern clinics and hospitals, is slow and halting. The young man finds out quite soon that he must learn first to be a medical student; how he will act in the future, when he is a doctor, is not his immediate problem.

Becker, Geer, Hughes, and Strauss,

Boys in White: Student Culture in Medical School

Contents

Authors Note

We call on physicians at birth and death and every significant medical event in between, but we rarely consider the personal challenges faced by those on their way to becoming our sages and saviors. From 2005 through 2009, I followed three students as they became doctors at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. The resulting series, White Coats, appeared in Cleveland Magazine in five separate issues over four years.

From the beginning, I focused on the human challenges involved in becoming a doctor. Regardless of curriculum or culture, a transformation takes place. I brought the readers into the settings of this transformationthe anatomy labs, classrooms, and hospitals where the students beheld their first cadavers, took their first pulses, and witnessed their first births. I explained significant issues in medical education through the students struggles to master the ever-increasing load of medical science, confront problems of professionalism, and learn the importance of empathy. I also chronicled the students personal sacrificescrushing debt, round-the-clock work, and neglect of family, friends, and health. The series revolved around one question: How does one grow into the white coat?

In this book, I revisit the reporting I did over four years and add more history and context, as well as details that didnt make the magazine series, which was limited by space restraints. As a result, the book includes more research and greater insights.

Like anyone reading this, I have turned to doctors in times of need. I have been a patient and a family member of patients, and I will be again. The way doctors are educated affects us all. I reported on medical school from the medical students perspectives, but I also told their stories as factually as possible. I approached this project as a reporter, double-checking the things students told me and running them through the why-anyone-else-should-care filter.

The audience for this book is medical educators and those considering medical school. But it is also a book for those who wonder about the personal challenges confronting the future doctors who will one day treat their cancer, alleviate their pain, and put them back together after car crashes. This work can help patients better understand their doctors. With understanding comes empathy, andI hopebetter doctor-patient relationships.

We are at a time, once again, of change in both medical school and health care in general. No matter what happens with legislation governing medical practice, however, doctors must continue to meet societys expectations of them. The specifics of how they are trained will evolvethe process by which my three subjects were educated just a few years ago has already changedbut those societal expectations will remain high, as they should for those society trusts with scalpels and prescription privileges. The book describes scenes that I observed and others that were reconstructed according to the students own memories and writings. When possible, I also interviewed patients, doctors, faculty, family members, friends, and others who were also present. All three of the students reviewed their parts of the book for accuracy before it was published.

The result is not a complete history of these students four years in medical school. Only full immersion in their lives would have made me qualified to produce such a work. Instead, I relay experiences that affected the students in ways significant to their development as physicians. Many of these experiences revolve around certain key themes other authors have noted in works about medical school, such as the immense quantity of material that must be learned, the intimate confrontation with death, and the indoctrination into the culture of medicine.

What goes into earning the long white coat is changing, but growing into it remains an astonishing feat. This work proves it.

Prologue

Doctors used to wear black. Like priests, they were called when sick people were out of other options. In the mid-nineteenth century, doctors still opened veins with spring-loaded lancets and bled arms over the indented lips of white basins. They still blistered and scarred. Before they knew how to prevent infection in surgery, they still operated with unsterilized knives and bone saws, their handles made of ivory, ebony, and tortoise shell. These tools arrived from London and Paris in special surgical kits, some made of mahogany and lined with velvet. The tools, like the kits, were beautiful, but as dangerous as the hands that wielded them.

At that time, getting a medical education was not difficult. Medical schools operated for profit, sometimes above a corner drugstore. Instruction was not rigorous. There were no entrance exams, no grades. Students were made doctors after listening to lectures, reading textbooks, and doing whatever clinical duties their doctor-instructors (called preceptors) requiredmixing herbs, bandaging wounds, physically restraining patients during operations.

Kent, Ohio

Kent, Ohio