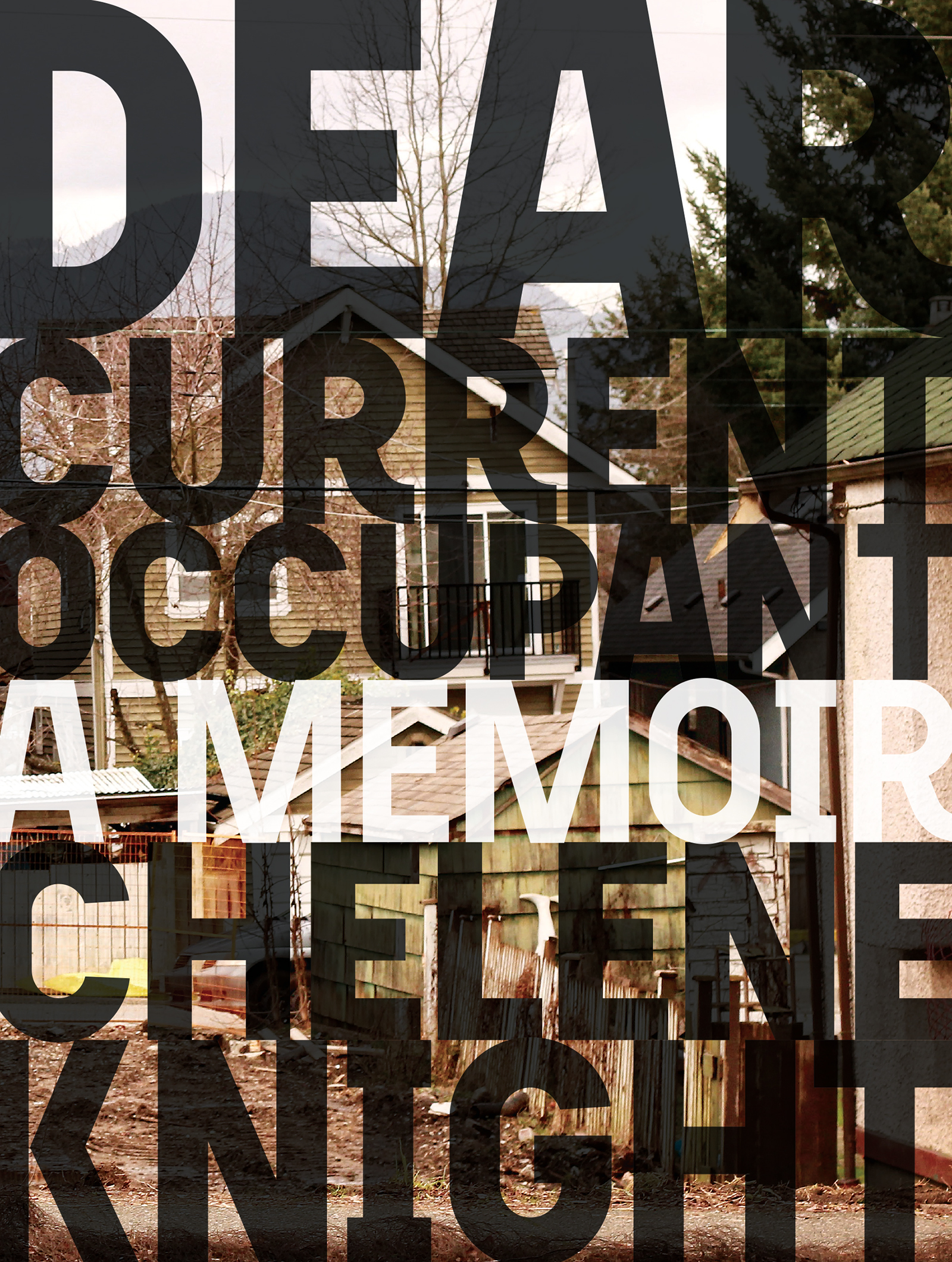

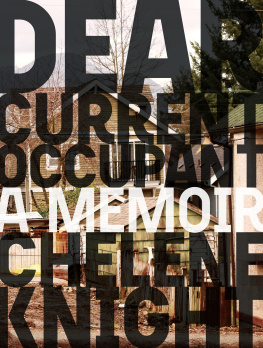

I think about all the houses

and I try to remember the little detailsI used to cough from the mixed fumes in the air, while Mamas cigarette smoke and pine cleaner pinned my eyelids to my brows. I try to remember the way Id only eat a handful of things. I was picky. I was skinny. My hair was big but I had good hair. I had thin wrists and tiny ankles. I kept an inventory of my things. I was light-skinned. Everyone saw me from the outside in. Id never wear my hair down.

There were so many houses. Never mine, never ours. These housescarpets, floors, cupboards, missing closet doors, light bulbs, faucets, shelves, bathrooms, shower curtains, phone cordsconstantly changing. Vancouver Eastside. Let me count the times the front door would slam in the middle of the night and the hinges squeak, lost in the breath of men Mamas visitors would come and go, never staying long enough to remember my name. My name, the skin-crawling sensation of a voice asking something, and then, No, thats my daughter.

Twenty or thirty houses. Many close together, some on the same block. I loved this city. Walk with me: Fraser, Kingsway, Clark, East 12th, Commercial, Broadway, Woodlands, Earles, 49th. Hold your things close. Sometimes we had to leave at a moments notice, taking only what we could carry and leaving behind what we couldnt. We filled shopping carts, baskets, boxes, garbage bags, backpacks. I noticed the colour of paint, walls, and doors. I took shelter in the frames of small spaces I thought no one would see.

The cracks in the sidewalk

I wanted to crawl in. It wasnt all bad: like the days I fell into books. Reading about being someone else. In each of these houses I spent my days writing about being someplace where I could mouth the word home and mean it. I wanted a corner nook where I could line my books along a wide windowsill. I wanted a large armchair, tall enough that my legs would swing and hover above a tiled floor. Id be safe. I could settle into my brothers laughter at jokes neither of us understood. Id dream of days spent listening to music. Id lie on my bed, turn up the radio, and close my eyes. Music played just for me.

I was eleven when I realized there could be music woven into words. Rhythms and cadence shifted in between colons and dashes. I was eleven when my teacher told me to sing loud. I was eleven when I realized I had a voice, and that everyone deserved to be heard. I wanted to sing loud. When I turned twelve, one of my classmates called me a nigger. It was at that moment I learned how to open my mouth and speak.

Sing loud, she said. This blond white woman balancing in three-inch heels hovered over me. Her wide body created a criss-cross design of shadow and light.

Sing loud, she said.

She pulled me into the dim cloakroom, where yellow, red, green, and brown raincoats lined the wall like infantry. I stood there in the dark of her dress. She placed the palm of her hand on my shoulder. Never let anyone say that to you again. Dont let anyone dull your shine.

I stood there confused, quiet. She lowered one knee to the ground, and her gaze met mine. I stuck my index finger inside my tightly sculpted hair bun, searching eagerly for scalp.

Why, miss? I continued to scratch inside my hair bun.

Because youre going to grow up to be a strong Black woman. Hasnt anyone ever told you that?

I remember that day in that cloakroom. I never wanted to be a woman. I never wanted to be a Black woman because I had no idea how.

This is for the teachers.

Growing up, I never had a Black teacher. I never had a Black woman teacher. I never had a Black or mixed-race teacher. I never had a Black or mixed-race woman teacher who understood what it was like to grow up poor, to live with a mother who struggled with addiction and sex work, or be a child forced to carry the weight of a low-functioning adult on her shoulders while trying to get an education. And I never once questioned this. Until now.

Why does this matter? Teachers hold a lot of power. Teachers are gatekeepers. I will not dance around this. How can a little Black girl be guaranteed shes offered the same opportunities as all the other children in her classes? Weve seen the movies that now centre around this very question, but is that enough? How do they challenge her, support her, teach her? How do teachers make sure that girl can sit calm at her desk without the worry that she isnt good enough, and that what she has to say isnt good enough? How do they guarantee that her voice will be heard? All of these questions and thoughts formed twenty-five years later. Now, as an adult, a mother, a professional writer, and an editor, I can see the cracks in the narrative.

Looking back at my younger self, I wonder what would have changed for me had I ever been handed a book written by a Black female author. How might that have influenced my life? A big question. Dionne Brand, Jamaica Kincaid, Toni Morrison, Esi Edugyan, Cecily Nicholson, to name just a few. What are the reasons names like these never crossed my desk?

![Jamie Knight [Jamie Knight] - Revealing His Virgin](/uploads/posts/book/141323/thumbs/jamie-knight-jamie-knight-revealing-his-virgin.jpg)