Narcissus Tazetta, one of the oldest daffodil varieties and most widely travelled, as drawn by the German botanical artist Georg Dionysius Ehret (17081770).

Amana Images

For my parents

CONTENTS

Guide

A Narcissus eye-view of my parents home, and my mothers garden, at the height of daffodil season with Emperor standing regally in the foreground. When it first appeared in 1869 this Division 1 trumpet, the progeny of pioneering English breeder William Backhouse, was considered one of the finest specimens ever seen.

He that has two cakes of bread let him sell one of them for some flowers of the Narcissus, for bread is food for the body but Narcissus is food of the soul.

attributed to Mohammed

(c. AD 570632)

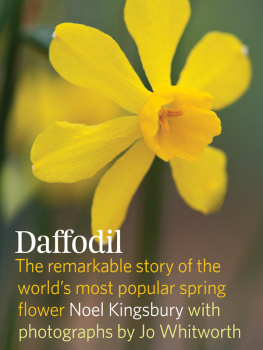

Daffodils have been part of my life for as long as I can remember. Born in Hampshires New Forest my roots lie deep in the rich soil of southern England, yet my childhood was one of perpetual motion as my family moved from one home to another, prompted by advances in my fathers career.

Across my ever-changing world daffodils became a constant. As each winter receded they appeared anew, a radiant signal that the bleakest English season was done with and the New Year truly on its way. By the time I hit my teens my familys travelling halted, and we settled in the countryside a few miles from a Thames Valley village. My new home was surrounded by towering woodland dissected by pathways that had been trod for centuries, dappled meadows carpeted all-too-briefly with bluebells and each spring what felt like acres of drifting daffodils.

It was then I absorbed the fact, without ever having to think about it, that the daffodil is not one flower but many. Ours blossomed in a prismatic kaleidoscope of colours from tissue paper white to the deepest blood orange and in a melange of flower forms and sizes. Some were elfin, others giants brandishing flowers that ranged in shape from classic golden trumpets to creamy stars with twisting petals and tiny butter-lemon cups.

As one daffodil variety melted away another materialised to take its place, a rhythmic dance through the spring chill that lasted, it seemed to my young mind, for ages. The blossoms were beautiful, injecting a lifeblood of colour into the drained winter landscape and we took them for granted. After all, they were simply daffodils.

As an adult I transplanted myself to Sydney on Australias dazzling east coast, a magical place where technicolour parrots wheel about like rambunctious toddlers, fruit bats are the size of pussycats and the indigenous foliage appeared to my eye alien indeed.

Yet cut bunches of daffodils appeared in flower shop displays early each spring and daffodils could be seen scattered across gardens in this arid continents cooler regions. They, like me, could not be called native yet clearly felt at home, particularly in the mountains of Victoria and New South Wales, the high districts around Perth in Western Australia and in certain locations across Tasmania and the landlocked ACT.

I lived in Sydney for decades and acclimatised completely, or so I thought. In late 2008 the opportunity arose to move back to Europe for six months and take up an Australia Council literary residency in a Paris apartment called the Keesing Studio. My partner and I boxed up the contents of our Bondi home, packed our warmest clothes and moved into the cosy atelier on the Right Bank of the River Seine.

It was early February and Paris was at its most desolate, winter having drained every atom of colour from the city. Impulse drove me to a cramped garden supplies store where I bought window boxes, potting mixture and dozens of miniature daffodil bulbs. I planted the little zombies as deep as the window boxes would allow, fired up my computer and immersed myself in work.

Gradually the plants emerged from the chilled soil, their razor-sharp leaves slicing into the air before their stems budded and burst into bright yellow flowers that faced down the end of winter and danced with the spring breeze. These daffodils blossomed for almost a month, ushered in the warmer weather and then, just as stealthily, faded away.

At the end of my Parisian stay I cleared out my window boxes, brushed the soil from the bulbs and sealed them inside a large, white envelope which I stowed away into a drawer. That is where Sophie Masson, a French-Australian childrens author, found them at the beginning of her winter Keesing Studio stay. Delighted, she told me she immediately replanted the bulbs. They made her feel intimately connected with the frozen city and filled her with reassurance that whatever else might happen, spring, and the blossoms, would come.

Later that same year back in Sydney I received a shock diagnosis of breast cancer. Emotionally my world froze in the face of one of the most witheringly hot summers I had ever experienced. I underwent surgeries and embarked on long rounds of chemotherapy, radiotherapy and finally hormone treatments. As my cancer-fighting regime progressed and I became weaker, in the northern hemisphere winter gave way to spring. Across my parents gardens the daffodil army mustered and bloomed.

My brother started photographing the daffodils and sending me his glorious pictures. His intention was to convey a message of hope, to help me realise the hard times would pass and that life would again be bright. He was not the only person to use the daffodil as an emissary. A friend in Melbourne who had herself beaten cancer posted me a sweet package of soft, cotton headscarves with a note, written in a card decorated by a lovely line-drawn image of Narcissus poeticus, letting me know I could ring any time. Another well-wisher from America sent me words of cheer and a beautiful, pink, stylised daffodil pin.

Daffodils fracturing Englands wintery grassland at The Stray, in Harrogate, North Yorkshire.

Amana Images

My brother was right, the hard times did pass, and as I began to recover I started thinking about the daffodil.

My parents had inherited a remarkable landscape where, each spring, a multitude of daffodils bloomed in flashes, clumps and languid drifts. My mother was entranced. On a whim she severed the stems of some particularly fine specimens and entered them in the village show. She returned home with prize certificates for best blooms and a prestigious silver cup. The following year she entered another batch. The same thing happened again.

My mother had by now picked up some tricks when it came to exhibiting. She found that the best times to pick her flowers were early in the morning or late in the afternoon. Whether she used a knife to cut the stems or flexed them hard until they snapped, she held the broken ends uppermost in her hand to stop the sap running out. She kept a bucket of water handy and popped each daffodil in as quickly as she could. Critically, she honed her sense of which blooms to select, how to sidestep pre-show stem and petal stress, and when to fire up her hairdryer in order to coax stubborn buds into opening in time for their big moment.