A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Allen, John.

Rabble-rouser for peace: the authorized biography of Desmond Tutu / John Allen.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Tutu, Desmond. 2. Church of the Province of Southern AfricaBishopsBiography. 3. Anglican CommunionSouth AfricaBishopsBiography.

I. Title.

Prologue

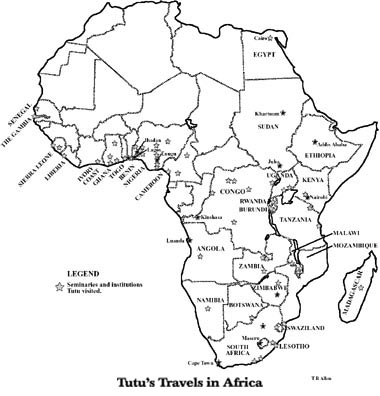

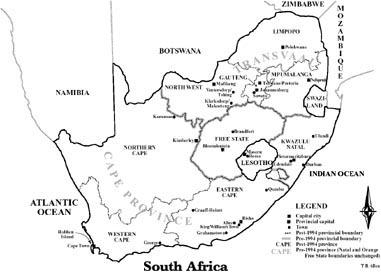

Desmond Tutu tensed in the backseat of his car as he left Bishopscourt, his official residence as Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, late in the afternoon of Wednesday, March 16, 1988. A tight knot formed in the pit of his stomach. Usually this happened when he was summoned to defuse confrontations in the citys black townships, regular occurrences in which he often stood between two groups spoiling for a fight: on the one side, defiant students carrying bricks and stones; on the other, heavily armed policemen with fingers on their triggers. Today was different. As Tutus chaplain and driver, Chris Ahrends, drove out through the imposing white gate posts, he turned north toward the city center (downtown Cape Town), where the archbishop had an appointment at Tuynhuys, the Cape Town office of P. W. Botha, also known as Piet Wapen (Piet Weapon) or die Groot Krokodil (the Great Crocodile). Botha was the state president of South Africa.

The thirteen-kilometer (eight-mile) drive from Bishopscourt to Tuynhuys offered an array of snapshots symbolizing past and current oppression. Bishopscourt was part of an estate owned by South Africas first white settler in the seventeenth century. The archbishops homea large whitewashed two-story mansion with acres of gardenswas the oldest privately owned house in the country. The agapanthus and cannas that grew there were said to come from stock planted by Dutch colonists. Beyond the estate, to the south, were the remains of a wild almond hedge, grown by the colonists to keep out of their settlement the likes of Tututhe indigenous people of South Africa. In 1988, Tutus second year as archbishop, he was living in Bishopscourt illegally, having refused to ask for permission to live in what apartheid designated a white area.

The route into the city ran along the eastern flank of Table Mountain, originally covered by fynbos (fine, or delicate, bush), the beautiful vegetationunique to the southwestern tip of Africathat makes up the smallest and richest of the worlds floral biomes. Now the slopes were built up and occupied by the wealthiest Capetonians, whites who had displaced the fynbos with big houses and gardens in which they grew foreign, if also beautiful, plants from their countries of origin. As Tutus car rounded Devils Peak on the northeastern corner of the mountain, he could look out over Table Bay, the harbor that had attracted Dutch sailors as a refreshment station on their way to the east. Beyond the harbor was Robben Island, used since the earliest days of colonialism to jail any who dared resist the incursions of the settlers. Farther down the hill, just before the car dipped into the city center, an enormous scar of overgrown, rubble-strewn land came into view. This was District Six, which had been a shabby and poverty-stricken, but nevertheless a vibrant and thriving multiracial community until the 1960s, when Botha initiated a process that led to its destruction and the deportation of its people to windswept sandy wastes far out of town.

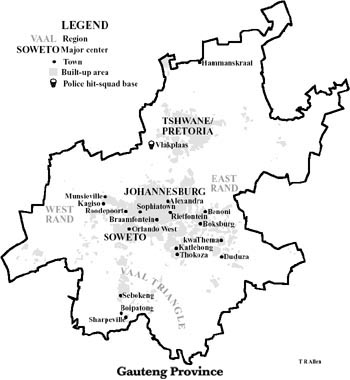

Ahrends pulled up at Bothas office a few minutes before 6 PM. This building too dated back to Dutch rule: the original structure, de Tuynhuys (the Garden House), had been built by the Dutch East India Company as a guesthouse alongside the gardens which supplied passing ships. Tutu had been there before, but never at a time of such high tension between church and state. Three years earlier, in September 1984, the third major uprising against apartheidthe one that was to start its final collapsehad begun in the industrial area around the Vaal River, south of Johannesburg. Just a few weeks previously, on February 24, 1988, Bothas police minister, Adriaan Vlok, had outlawed the activities of seventeen organizations involved in the uprising, including coalitions representing two of the countrys largest political forces. In response, the South African Council of Churches had convened an emergency meeting of church leaders, who resolved to pick up where the banned organizations had left off. The church leaders also decided to fly to Cape Town, seat of South Africas parliament, to convey their decision to the government.

On Monday, February 29, 25 church leaders and about 100 other clergy and lay workers gathered at St. Georges Cathedral, Cape Town, which backed onto the government complex incorporating Parliament and Tuynhuys. At a short service, the general secretary of the Council of Churches, Frank Chikane, read out a petition addressed to Botha and members of Parliament. The Anglican activist Sid Luckett instructed members of the congregation in the precepts of nonviolent direct action. He warned them that although the police, already swarming outside, were unlikely to use tear gas in the city center, they had used dogs, sjamboks (rawhide whips), and water cannons before.

Then, row by row, arms linked, the congregation went out of the cathedral, the church leaders wearing their robes of office, intent on delivering the petition to Parliament. In the front row were Tutu; Chikane; the Catholic archbishop of Cape Town, Stephen Naidoo; the president of the Methodist Church, Khoza Mgojo; and the president of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches, Allan Boesak. A line of blue-uniformed policemen, arms also linked, swung out across the street to block their way. An officer with a bullhorn told the protesters that their action was illegal. He warned them to disperse. They refused and knelt on the sidewalk. The police arrested the leaders, marched them away, and then opened up on the rest of the procession with a water cannon. A few of the clergy clung to parking meters, but others were sent tumbling down the street. That night, BBC Televisions South African correspondent told his viewers: The church has unmistakably taken over the front line of antiapartheid protest.

However, the church leaders protest was not the subject of Tutus appointment at Tuynhuys on March 16. He was there on a pastoral mission, to plead for the lives of the Sharpeville Six, five men and a woman facing execution. They were from an area best known for a massacre that took place there in 1960, and they had been convicted of killing the deputy mayor of Sharpeville on the first day of the Vaal uprising in 1984. Their case had generated an international campaign for clemencynot only had the police investigators assaulted witnesses and suspects, but most of those convicted were accused not of contributing directly to the deputy mayors death but simply of being part of a crowd acting in common purpose with the killers. On Monday, March 14, the sheriff of the Supreme Court in Pretoria had informed the six that they were to be hanged on Friday, March 18. Wardens had measured the circumference of their necks, and their heights and weights, so that the hangman could calculate the size of the nooses and the length of the ropes. Then the prisoners had been led to a place in Pretorias Central Prison that was called the pot because its occupants emotions were said to boil over as they contemplated their death.