To Roro, our children and grandchildren

DMT

To Joe, Nyaniso, and Onalenna

MAT

Contents

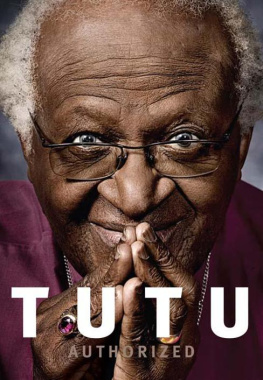

I speak to audiences across the world, and I often get the same questions: Why are you so joyful? How do you keep your faith in people when you see so much injustice, oppression, and cruelty? What makes you so certain that the world is going to get better?

What these questioners really want to know is, What do I see that theyre missing? How do I see the world and my role in it? How do I see God? What is the faith that drives me? What are the spiritual practices that uphold me? What do I see in the heart of humanity and in the sweep of history that confi rms my conviction that goodness will triumph?

This book is my answer.

I have written with the help of my youngest daughter, Mpho. Like me, she is a priest in the Anglican Communion. We are both parents, both married, and we share some core beliefs. But each of us has our own unique life experience that we bring to this book.

Our experience, our reading of Scripture, and the people who have been a part of our liveshowever brieflyhave taught us some important truths that we will share with you in this book. First, we will see that we are all designed for goodness, and when we recognize that truth it makes all the difference in the world. Second, we are perfectly loved with a love that requires nothing of us, so we can stop being good and live into the goodness that is our essence. And third, God holds out an invitation to usan invitation to turn away from the anxious striving that has turned stress into a status symbol. It is an invitation to wholeness that leads to flourishing for all of us.

We also know that God has given us the gift of freedom and that in order for freedom to be real, we must be free to choose right and equally free to choose wrong. With our freedom comes certain hard questions: Where is God when we suffer? Where is God when we fail? Why does God let us sin? And when we do suffer, fail, or sin, how do we find our way home to goodness? How can we rediscover our essence? We will explore these questions together. We will also describe some of the ways we have learned of hearing Gods voice offer us comfort, guidance, answers, and acceptance. When we are able to hear Gods voice and see with Gods eyes, we will be able to see the world as it truly is.

We will explore the truths and address the questions using the stories that have shaped our outlook. Our world-view was forged in the fi res of apartheid South Africa and in the course of marriage and parenting, and so we will share many stories from our homes and our history. You will also become familiar with some of our favorite Bible stories. Whether you read the Bible as sacred text or just as good literature, the stories it contains tell us deep and abiding truths about human nature. We return to them again and again in our teaching and preaching and in our private prayer andstudy.

We invite you to join us on a pilgrimage. Come and see some of the places we have seen. Come and share some of the lessons we have learned. Come and meet some of the people we have known. Walk with us on holy ground. Perhaps you will learn to see yourself through Gods eyes and come to know that your whole life is holy ground.

I mpimpi! (Informer!)

In the bad old days of apartheid the accusation was deadly. Any black person suspected of collaborating with the hated South African security police risked a grisly death. Here the suspected informer was down on the ground, beaten and bloodied. Tempers in the crowd were already frayed. It was yet another in a long procession of the struggle funerals: Duduza Township, east of Johannesburg, in July 1985. It was thought that police had killed the four young men we had come to bury. And now the crowd had their hands on a man they accused of being a police spy. They were preparing the petrol-filled tire that was to be his fiery necklace.

Without pausing to think, I waded into the middle of the angry mob. Do you accept us as your leaders? I asked. They seemed rather reluctant, mumbling. If you accept us as your leaders, you have to listen to us and stop what you are doing. As I desperately tried to reason with the crowd a car arrived, and my colleague Bishop Simeon Nkoane was able to spirit the injured man away. It was only afterward, when I saw it on television, that I considered my own peril. I tell this not as a story of my heroism but as an illustration of the violence we can inflict upon one another.

I am no dispassionate observer of the litany of crime and cruelty that assaults us at every turn. For three long years I served as the chairman of South Africas Truth and Reconciliation Commission, our attempt to cleanse our nations soul from the evil of apartheid. For days on end I listened to horrific stories of abuse. I cannot tell you how many times my heart broke as I listened to the confessions of perpetrators and the testimony of victims. Indeed, at times I became sick to my stomach at the horror of what I heard.

It is not only what I have heard of human depravity that has made my stomach churn, but also what I have seen. As the president of the All Africa Conference of Churches, I made a pastoral visit to Rwanda in 1995, a year after the genocide. I went to Ntarama, where hundreds of Tutsis had fled to the church for safety. The year 1994 was not the first time that interethnic violence had gripped Rwanda. With each previous eruption of fighting any church became a refuge, a sanctuary from the insanity beyond its walls. In 1994 the Hutu Power movement respected no sanctuary. Tutsi people were slaughtered in churches throughout Rwanda. The Ntarama church was no different. It provided no safety for the people, mostly women and children, who had cowered there. The floor was strewn with a record of the horror that had occurred in that place. Clothing and suitcases were scattered among the bones. The small skulls of children lay shattered on the floor. The new government had not removed the corpses, so the church was like a mortuary, with the bodies lying as they had fallen the year before. The stench was overpowering. Outside the church building was a collection of skulls, some still stuck with machetes and daggers. I tried to pray. I could only weep.

All over the world people have inflicted unspeakable violence on other people. On missions to the Sudan, to Gaza, and to Northern Ireland I have borne witness to some of the viciousness that human beings can unleash on each other.

Brutality can be as intimate as it is global. Our cruelties are played out in the intimacy of our own homes and neighborhoods as much as they are experienced on the world stage. I have shared my daughter Mphos anguish as she has described some of her experiences in ministry to me. She has worked with rape survivors in South Africa: a fifteen-year-old girl who spent countless nights sleeping in the school bathroom to escape her fathers molestation and her mothers rage and impotence. Mpho cared for an eight-year-old girl twice violated by a neighbor. Because the neighbor had threatened to kill her family, the frightened child named someone else as the perpetrator the first time she was molested. It was only after the second assault that she dared to tell the truth. My daughter sat with an eighty-year-old woman brutalized by a stranger. She listened as the doctor who attended the victim struggled to contain her own distress: The genital lacerations were so ragged and awful, I hardly knew where to begin to sew her up. In Massachusetts, Mpho worked with women of many races and every economic stratum who had fled from domestic violence to homelessness. She has been with wealthy women too ashamed to turn to their friends for support or shelter, and poor women who had nowhere to go. She has provided pastoral counseling to families struggling with the effects of substance abuse: loss of livelihood, loss of self-respect, frayed family ties, and, often, violence.