Copyright 1991 by Dennis Overbye

Afterword 1999 by Dennis Overbye

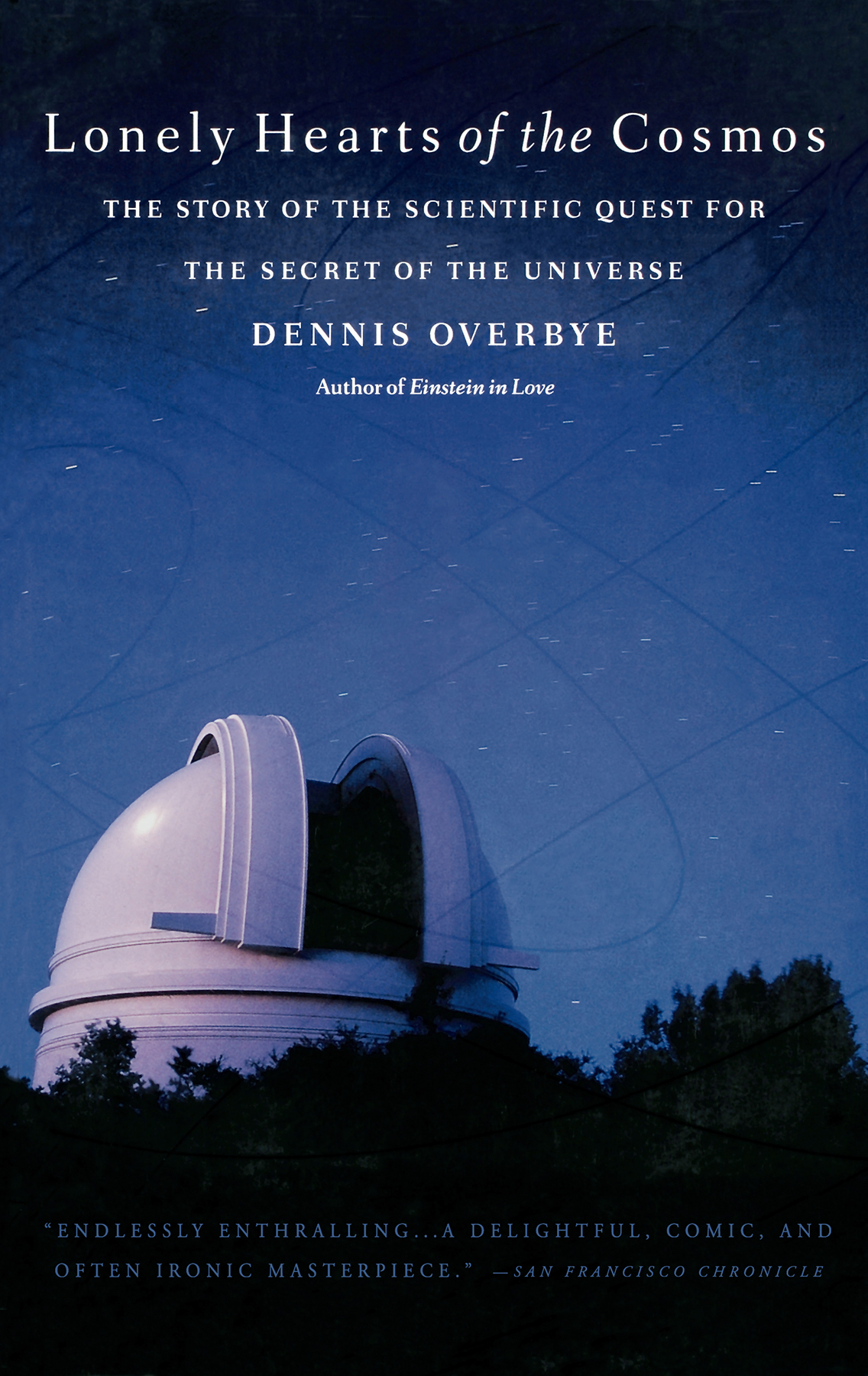

Cover design by Amy Goldfarb

Cover photograph by David Hogg, Palomar Obs/Caltech

Cover copyright 1999 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: December 2021

Previously published in paperback by Back Bay Books / Little, Brown and Company, 1999

Originally published in hardcover by HarperCollins Publishers, 1991

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-43479-9

E3-20211113-JV-NF-ORI

An excellent book. A rollicking, warts-and-all home movie of a family of astronomers, particle physicists, astrophysicists, and assorted hangers-on. Viewed in action, these intellectual high-wire performers are unforgettable. Overbye tries to uncover what makes these priests and mythmakers of our technological age run. And he succeeds brilliantly.

John Wilkes, San Francisco Chronicle

Overbye seems determined to break the formulaic pattern of science writing. The characters who walk the immense stage of Lonely Hearts are wonderful.

Richard M. Preston, Los Angeles Times

Compelling sometimes suspenseful, often poignant human dramas. Overbye spins this complicated yarn with eloquence and wit.

John Carey, Business Week

First-rate science journalism written with intellectual sophistication and dazzle.

Jeanne K. Hanson, Minneapolis Star Tribune

Mr. Overbye succeeds admirably in illuminating these matters [cosmological], as well as the eccentrics who fret and wrangle over them.

Jim Holt, Wall Street Journal

Overbye has discovered a fiendishly clever way of tricking readers into understanding cosmology. By describing the quirky personalities and brilliant minds of these scientists, he reveals cosmology to be a human and passionate enterprise. This lures the reader into wanting to know something of the science as well, which Overbye explains with care and clarity.

Time

Einstein in Love

For my mother and father

In 1954 Fortune magazine ran an article on the state of American science. Accompanying it was a photo essay featuring ten promising young scientists. One of them was an astronomer, who had been photographed leaning against the base of a famous 200-inch telescope on Palomar Mountain. He looked lean and Jimmy Stewartish, wearing a bomber jacket and grinning with dimpled cheeks, a spit of curl hanging over his high forehead. His eyes sparkled. He seemed both cocky and serious, like an ace bound for a battle with the Red Baron. All that was missing was the cigarette dangling from the lower lip. His name was Allan Sandage.

Sandage had a right to look cocky, and eager. At the time of the article, he was only twenty-eight, just a year past his Ph.D., and one of a handful of humans who had access to the 200-inch telescope, the most famous instrument of its time. Among that privileged few, he owned the darkest nights, the purest skies, the heaviest burden. As the magazine delicately put it, He is helping to define the age and structure of the universe.

It is a poignant image, this jaunty young man with dimples and his new telescope, and a poignant moment, one that crystallized the hope that science, with these new tools and bright eager men, could unravel the mystery of the cosmos. Allan Sandage had become the first person in history whose job description was to determine the fate of the universe.

Five years later and half a world away in India, a wandering religious scholar named Huston Smith had a strange encounter with the Dalai Lama, the spiritual and governmental head of Tibet who had fled into India after the Chinese invasion of his country. According to the traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, the Dalai, whose real name was Tenzin Gyatso, was the fourteenth reincarnation of the Buddhist god of compassion; in practice he was a curious fellow.

As Smith recounted it years later, an audience with God was usually a brief, formally scripted affair: few words were spoken; you said your lines, paid your respects, bowed, and left. Where are you from? asked the Dalai as part of the game. Smith, a slender, prematurely bald man, explained that he taught philosophy and religion at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Dalai Lama, an educated man, promptly abandoned ceremony, somewhat to Smiths surprise. Stick around for a few minutes, he said. I want to talk to you.

The Dalai went on to ask if Smith could tell him what was going on in the raging debate about the origin of the universe. Recently astronomers had coalesced into camps espousing two opposing versions of cosmic history. The first theorycalled the big bangheld that the universe had begun in a fiery cataclysm 10 billion years ago or so, and might end in an equally spectacular crash billions of years in the futurea notion splendidly redolent of the cycles of destruction and re-creation of the world that the Tibetan Buddhists called kalpas. The other theoryknown as the steady statemaintained that the universe was infinite and was forever the same. The Dalai listened attentively as Smith told him that, according to the latest words from Palomar, the balance was perhaps shifting toward the big bang. The Dalai Lama nodded and smiled ironically. Of course, he said, we have a position on that.

Its traditional for a book about cosmology to start by recounting the colorful creation myth of some ancient or primitive society, perhaps partly to show how far weve allegedly come. More important, it reminds us that the questions of who we are, where we come from, why we die, and why there is something rather than nothing at all are in our bones. I grew up in the sputnik generation of the fifties, maybe the first generation raised with a creation myth that was supposedly scientifically certifiable. The Palomar astronomers were then just beginning what would surely be the definitive exploration of the cosmos. My friends and I grew up readinglike the Dalai Lama, but perhaps with less personally at stakeabout the debate between the big bang and the steady state, about curved space-time, the mystery of the expanding universe, and energy and matter transforming themselves into each other.

We were raised on science fiction movies and the presumption that mankind would conquer space and discover amazing mystical things about the origin of the universe