Contents

Landmarks

Page Navigation

2020 Linda Schweizer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

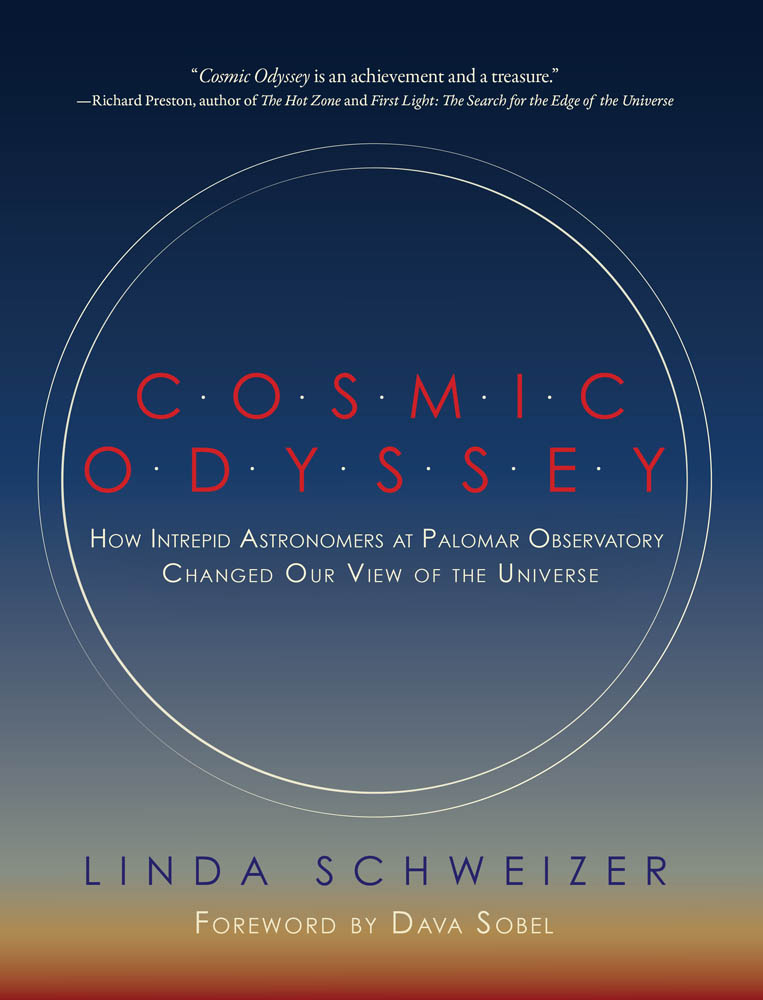

Cover design, design, and composition by Briana Schweizer

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Schweizer, Linda Younker, author.

Title: Cosmic Odyssey : How intrepid astronomers at Palomar Observatory changed our view of the universe / Linda Schweizer.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019057055 | ISBN 9780262359658

Subjects: LCSH: Palomar Observatory--History. | Astrophysics--Research--California--History--20th century.

Classification: LCC QB461 .S3152 2020 | DDC 522/.1979498--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019057055

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

d_r0

To curious souls everywhere

T he most foolish question I ever asked an astronomer concerned a mammoth construction project that had already eaten up years of the mans time. Wont you be relieved, I ventured, when you can ditch the hard hat and get back to the real business of observing?

The scientist made no effort to hide his annoyance at my naivete. Building this instrument, he informed me coldly, was the single most important work of his life. He doubted whether anything he might discover with its aid would surpass the value of having guided the great light bucket from idea to realization.

I imagine George Ellery Hale might have told me much the same thing, had I been around to interrupt his activities. Ever hungry for more light, Hale managed to build the worlds largest telescope four times in the course of his career. He placed his first record-breaker, the 40-inch refractor of the Yerkes Observatory, near his native city of Chicago. That telescope (still the giant of its kind) was idled by the miserable local weather as many as two hundred nights per year. Hale turned west and lit out for California. He capped Mount Wilson with huge domes to house a 60-inch and later a 100-inch reflector. For his final triumph, he envisioned and initiated the fabrication of the 200-inch Hale telescope here on Palomar Mountain, but he did not live to see it see first light.

The magnificent instrument drew astronomers to Palomar. It even drew a few scientists from fields outside astronomyfor the promise and possibility of turning the Big Eye, as the Hale telescope came to be known, to some previously unexpected purpose. For although the 200-inch was attuned only to the wavelengths of visible light, it soon became an essential ally in the burgeoning fields of radio and infrared astronomy, and went on to help identify and characterize the sources of celestial outbursts of gamma rays and X-rays.

Findings made at Palomar repeatedly expanded the size of the known universe and altered prevailing views of its nature. Long before the Hubble Space Telescope endeared itself to earthlings as the peoples telescope, the Big Eye on Palomar Mountain funneled the cosmos into the popular imagination. What had once been seen as a realm of slowly evolving majesty, with isolated galaxies stealing ever farther away from us and from each other, was here revealed to be replete with violence: despite the vastness of space, galaxies could joust like enemy armies and plunder one anothers stars.

Observing in the early days of the 200-inch in the 1940s and 1950s meant climbing into its prime-focus cage and guiding the telescope through the dark as though it were a balky animal. Yes, the air was frigid, the quarters cramped, the stress considerable, but many who braved those nights recall them as joyrides into the universe. As one veteran observer interviewed for this book recounted, I was one hundred some-odd feet above the ground, and there was nobody else in the world. It was just me and the sky.

To say that a telescope functions as an extension of the astronomers senses is to overlook the deeper attachment that can form between them, as together they peel back the layers of interference between curiosity and knowledge.

Some years ago I attended a weeklong symposium of the International Astronomical Union, held in Padua. The organizers had arranged for one of Galileos original handmade telescopes to be put on display in a Plexiglas case in a central meeting area. The sight of it electrified the participants, who represented observatories and space agencies from all over the world. At any moment in the proceedings a cluster of them could be found standing transfixed around Galileos telescope. Compared to the equipment they were accustomed to handling, this cardboard and leather tube appeared as ancient and rudimentary as a flint axe, but they regarded ityou could almost say they venerated itas the fountainhead. Many of them carried childhood memories of getting hooked on astronomy with a starter scope more or less the same overall size and shape.

Today, most operations at Palomar proceed via robot control, and no one stands in the domes when observations are under way. The several instruments have been augmented through the decades with new detectors to extend their range, and adapted with optics to sharpen their view through Earths atmosphere. As the newfound ability to collect gravitational waves from stellar collisions widens the scope of astronomical research beyond the confines of the electromagnetic spectrum, this observatory remains vital, even beloved.

Linda Schweizers informed account of the science conducted here is an astronomers answer to The Thousand and One Nights. It speaks of geeky midnight assignations, of dogged devotion to data gathering, of theories tested and patience tried though rarely exhausted. Her separate stories flit from light to dark matter, from quasars to extrasolar planets, starburst supernovae, and other exotica. The tales are peopled by a large cast of characters who collaborate and compete, working with or for or around one another in the unique environment of Palomar. One smitten observeran astronomer-turned-astronautadmits to pilfering a small piece of the place, which he carried with him into orbit for his first mission aboard the space shuttle.

DAVA SOBEL

The benefits of astronomy accrue to the human mind, as telescopes gather neither gold nor jewels except as people experience them in thought.

ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS SURVEY COMMITTEE, chaired by John N. Bahcall, 1990

M any people dream of the stars. This book follows the astronomers who turn their dreams into hypotheses and discoveries on a cosmic scale. The Big Eyeas Palomar Observatorys largest telescope is affectionately knownplayed a significant role in those discoveries through much of the 20th century.

The casting of the Big Eyes 200-inch-diameter Pyrex mirror, the construction of its massive dome and horseshoe mount, and its first images of the universe generated as much public excitement as would the Apollo moon missions and the Hubble Space Telescope decades later. Dedicated as the George Ellery Hale Telescope in 1948 after the leading American astrophysicist and astronomical entrepreneur, it was constructed with funds provided by The Rockefeller Foundation. It was the worlds largest reflector for nearly 40 years and continues working at the forefront today. Just as Mount Wilson astronomer Edwin Hubble opened up the boundaries of the universe in the 1920s, so astronomers at Palomar wrote and rewrote the textbooks of astronomy in the mid to late 20th century. Through the Big Eye, the world encountered quasars and supermassive black holes, understood the chemistry that turns stardust into life, and pressed the limits of the known universe relentlessly outward.