Also by Dava Sobel

Longitude

Galileos Daughter

Letters to Father

The Planets

A More Perfect Heaven

And the Sun Stood Still (a play)

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

Copyright 2016 by John Harrison and Daughter, Ltd.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices,promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture.

Thank you for buying an authorized

edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing,

scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are

supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

: Angelo Secchi, Le soleil, 18751877.

: Courtesy of Carbon County Museum, Rawlins, Wyoming

: UAV 630.271 (E4116), Harvard University Archives

: Courtesy of Harvard College Observatory

: Courtesy of Hastings Historical Society, New York

: Lindsay Smith, used with permission

: Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

: UAV 630.271 (391), olvwork432043, Harvard University Archives

: Courtesy of Harvard College Observatory

: Courtesy of Harvard College Observatory

: HUGFP 125.36 F, Box 1, Harvard University Archives

: Courtesy of Katherine Haramundanis

: Courtesy of Charles Reynes

: Chart 1, Volume 105, Harvard College Observatory Annals

: Courtesy of Katherine Haramundanis

: Richard E. Schmidt, used with permission

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sobel, Dava.

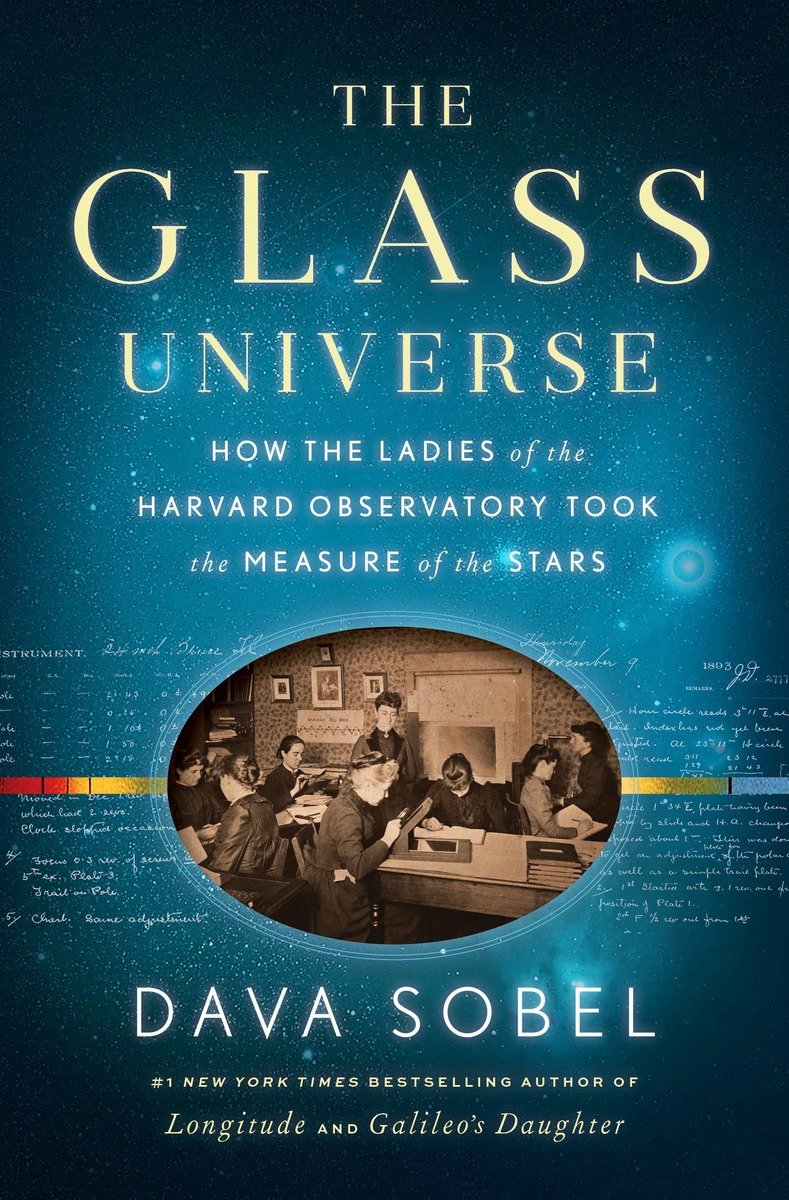

Title: The glass universe : how the ladies of the Harvard Observatory took the measure of the stars / Dava Sobel.

Description: New York : Viking, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016029496 (print) | LCCN 2016030208 (e-book) | ISBN 9780670016952 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780698148697 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Women in astronomyMassachusettsHistory. | Women mathematiciansMassachusettsHistory. | AstronomyHistory19th

century. | AstronomyHistory20th century. | Harvard College Observatory.

Classification: LCC QB34.5 .S63 2016 (print) | LCC QB34.5 (ebook) | DDC

522/.19744409252dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016029496

Printed in the United States of America

Version_1

To the ladies who sustain me:

Diane Ackerman, Jane Allen,

KC Cole, Mary Giaquinto, Sara James, Joanne Julian,

Zo Klein, Celia Michaels, Lois Morris,

Chiara Peacock, Sarah Pillow,

Rita Reiswig, Lydia Salant, Amanda Sobel,

Margaret Thompson, and Wendy Zomparelli,

with love and thanks

CONTENTS

PREFACE

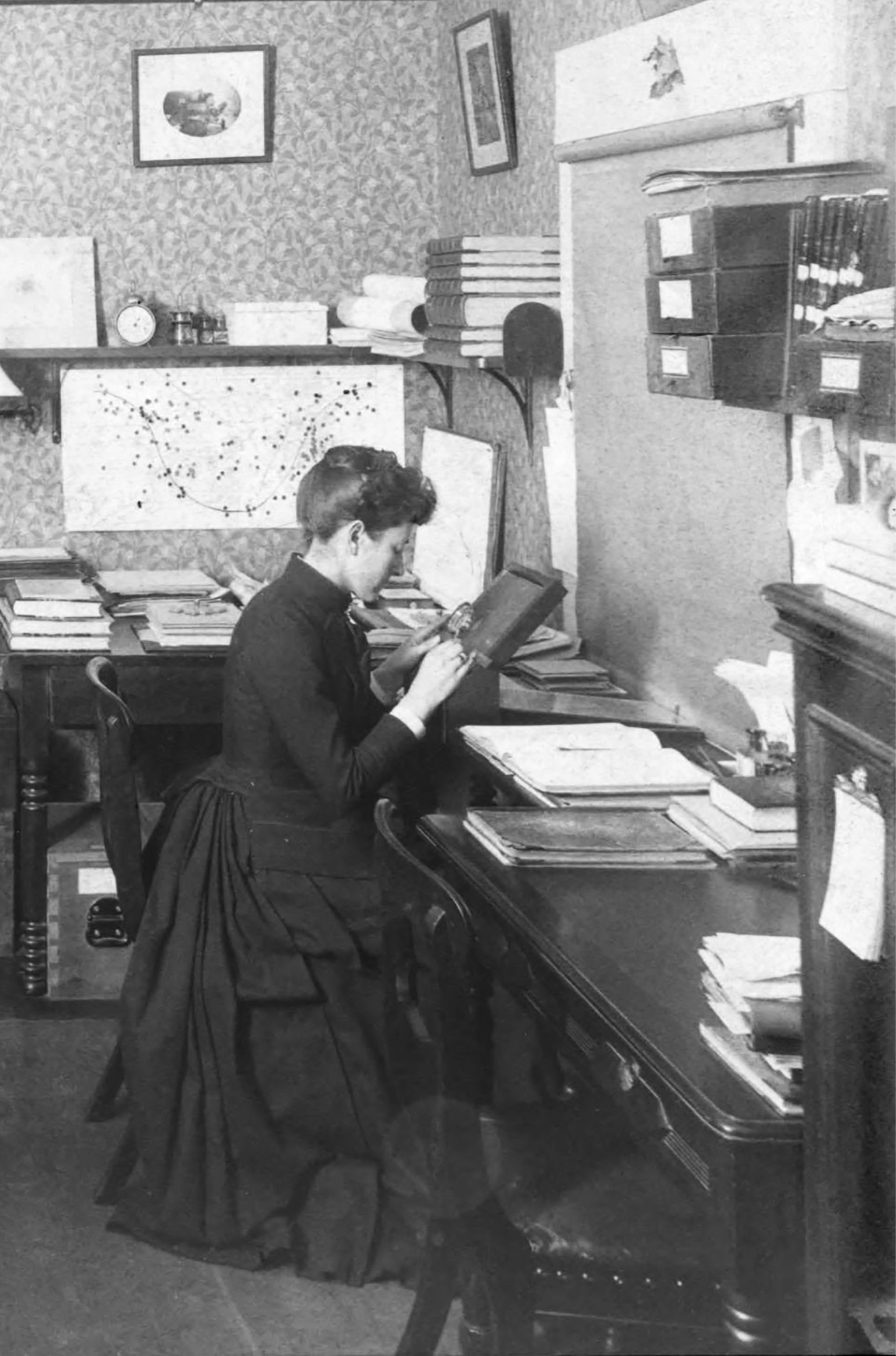

A LITTLE PIE CE OF HEAVEN. That was one way to look at the sheet of glass propped up in front of her. It measured about the same dimensions as a picture frame, eight inches by ten, and no thicker than a windowpane. It was coated on one side with a fine layer of photographic emulsion, which now held several thousand stars fixed in place, like tiny insects trapped in amber. One of the men had stood outside all night, guiding the telescope to capture this image, along with another dozen in the pile of glass plates that awaited her when she reached the observatory at 9 a.m. Warm and dry indoors in her long woolen dress, she threaded her way among the stars. She ascertained their positions on the dome of the sky, gauged their relative brightness, studied their light for changes over time, extracted clues to their chemical content, and occasionally made a discovery that got touted in the press. Seated all around her, another twenty women did the same.

The unique employment opportunity that the Harvard Observatory afforded ladies, beginning in the late nineteenth century, was unusual for a scientific institution, and perhaps even more so in the male bastion of Harvard University. However, the directors farsighted hiring practices, coupled with his commitment to systematically photographing the night sky over a period of decades, created a field for womens work in a glass universe. The funding for these projects came primarily from two heiresses with abiding interests in astronomy, Anna Palmer Draper and Catherine Wolfe Bruce.

The large female staff, sometimes derisively referred to as a harem, consisted of women young and old. They were good at math, or devoted stargazers, or both. Some were alumnae of the newly founded womens colleges, though others brought only a high school education and their own native ability. Even before they won the right to vote, several of them made contributions of such significance that their names gained honored places in the history of astronomy: Williamina Fleming, Antonia Maury, Henrietta Swan Leavitt, Annie Jump Cannon, and Cecilia Payne. This book is their story.

PART ONE

The Colors of Starlight

I swept around for comets about an hour, and then I amused myself with noticing the varieties of color. I wonder that I have so long been insensible to this charm in the skies, the tints of the different stars are so delicate in their variety.... What a pity that some of our manufacturers shouldnt be able to steal the secret of dyestuffs from the stars.

Maria Mitchell (18181889)

Professor of Astronomy, Vassar College

The white mares of the moon rush along the sky

Beating their golden hoofs upon the glass heavens

Amy Lowell (18741925)

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry

CHAPTER ONE

Mrs. Drapers Intent

T HE DRAPER MANSION, uptown on Madison Avenue at Fortieth Street, exuded the new glow of electric light on the festive night of November 15, 1882. The National Academy of Sciences was meeting that week in New York City, and Dr. and Mrs. Henry Draper had invited some forty of its members to dinner. While the usual gaslight illuminated the homes exterior, novel Edison incandescent lamps burned withinsome afloat in bowls of waterfor the amusement of the guests at table.

Thomas Edison himself sat among them. He had met the Drapers years ago, on a camping trip in the Wyoming Territory to witness the total solar eclipse of July 29, 1878. During that memorable interlude of midday darkness, as Mr. Edison and Dr. Draper executed their planned observations, Mrs. Draper had dutifully called out the seconds of totality (165 in all) for the benefit of the entire expedition party, from inside a tent, where she remained secluded, blind to the spectacle, lest the sight of it unnerve her and cause her to lose count.

The red-haired Mrs. Draper, an heiress and a renowned hostess, surveyed her electrified salon with satisfaction. Not even Chester Arthur in the White House lighted his dinner parties with electricity. Nor could the president attract a more impressive assembly of sciences luminaries. Here she welcomed the well-known zoologists Alexander Agassiz, down from Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Spencer Baird, up from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. She introduced her family friend Whitelaw Reid of the