PUBLISHED TITLES IN THE GREAT DISCOVERIES SERIES

David Foster Wallace

Everything and More: A Compact History of

Sherwin B. Nuland

The Doctors Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever,

and the Strange Story of Ignc Semmelweis

Michio Kaku

Einsteins Cosmos: How Albert Einsteins Vision Transformed Our

Understanding of Space and Time

Barbara Goldsmith

Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie

Rebecca Goldstein

Incompleteness: The Proof and Paradox of Kurt Gdel

Madison Smartt Bell

Lavoisier in the Year One:

The Birth of a New Science in an Age of Revolution

George Johnson

Miss Leavitts Stars: The Untold Story of the Woman

Who Discovered How to Measure the Universe

FORTHCOMING TITLES

David Leavitt on Alan Turing and the Computer

Richard Reeves on Rutherford and the Atom

Daniel Mendelsohn on Archimedes and the Science of the Ancient Greeks

William T.Vollmann on Copernicus and the Copernican Revolution

David Quammen on Darwin and Evolution

General Editors: Edwin Barber and Jesse Cohen

BY GEORGE JOHNSON

Architects of Fear: Conspiracy Theories and

Paranoia in American Politics

Machinery of the Mind: Inside the New Science of Artificial Intelligence

In the Palaces of Memory: How We Build the Worlds Inside Our Heads

Fire in the Mind: Science, Faith, and the Search for Order

Strange Beauty: Murray Gell-Mann and

the Revolution in Twentieth-Century Physics

A Shortcut Through Time: The Path to the Quantum Computer

Miss Leavitts Stars: The Untold Story of the Woman

Who Discovered How to Measure the Universe

GEORGE JOHNSON

Miss Leavitts

Stars

The Untold Story of

the Woman Who Discovered

How to Measure the Universe

ATLAS BOOKS

W.W.NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright 2005 by George Johnson

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions,W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Manufacturing by R. R. Donnelley, Harrisonburg Division

Book design by Chris Welch

Production manager: Julia Druskin

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Johnson, George, date.

Miss Leavitts stars : the untold story of the woman who discovered how

to measure the universe / George Johnson. 1st ed.

p. cm. (Great discoveries)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-393-05128-5

ISBN 978-0-39334-837-8 (e-book)

1. AstrometryHistory. 2. Leavitt, Henrietta Swan, 18681921. 3. Astronomical photometry. 4. AstronomyUnited StatesHistory20th century.

I. Title. II. Series.

QB807.J64 2005

522'.09'04dc22

2005002823

Atlas Books, 10 E. 53rd St., 35th Fl., New York NY 10022

W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W.W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

For my mother, Dorris M. Johnson

, and if she squinted at them, the confetti of inklings began to resemble a skyful of stars. She had time to let her mind wander. The Magis search for Bethlehem; the music of Miltons crystal spheres... they could all be reduced to these numbers. There was actually no need to squint and pretend that the digits were the stars. They were, by themselves, wildly alive, fact and symbol of the vast, cool distances in which one located the light of different worlds.

THOMAS MALLON, Two Moons

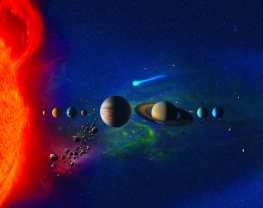

, they travelled together from the earth to Uranus, and the mysterious outskirts of the solar system; from the solar system to a star in the Swan, the nearest fixed star in the northern sky; from the star in the Swan to remoter stars; thence to the remotest visible; till the ghastly chasm which they had bridged by a fragile line of sight was realized....

THOMAS HARDY, Two on a Tower

Contents

H enrietta Swan Leavitt deserves a proper biography. She will probably never get one, so faint is the trail she left behind. No personal diaries, no boxes of letters, no scientific memoirsshe wasnt one to brag. She rates no more than a few paragraphs in the biographical reference books, the Whos Who of this or that, a footnote or a boxed sidebar in the Astronomy 101 texts.

I had intended to use her as nothing more than a device, a way to get into the story of how, in the 1920s, people learned that there is more to the universe than just the Milky Way. The discovery she made in her menial position at the Harvard Observatory was the turning point. I figured I would make that turn in the first chapter and then move on.

But Henrietta Leavitt refused to exit on cue from the story. I couldnt get this woman out of my mind. Why, given the remarkable, completely unexpected nature of her observation, didnt she push beyond it, working shoulder to shoulder with the great Harlow Shapley and Edwin Hubble, as they grabbed onto Henriettas law and ran with it light-years across the sky?

And so, just when I thought the book was almost done, I found myself going back to the beginning, searching her genealogy, scouring the records as they had apparently not been scoured before. Scrap by scrap, the apparition in the canned biographical sketches was replaced by a human beingnot solid enough, perhaps, to star in her own biography but someone with a story to tell.

T he was hidden at the bottom of a deep chasm with sides so steep and slick that no one had ever climbed them. All that could be seen overhead was a narrow band of sky.

Looking down the canyon, one could spot a hill in the distance. How distant no one knew, for it was separated from the village by an impassable expanse. Beyond the hill, and even more inaccessible, was a faraway mountain, the edge of the knowable world.

The villagers had noticed that when they walked the width of their canyon, from one wall to the other, the top of the hill appeared to shift ever so slightly against the backdrop of the mountain, moving from one side of the peak to the other. No one believed the hill really moved, but they enjoyed the illusion.

One day a particularly observant citizen noticed an interesting subtlety. When he wandered up the canyon a ways, and then traversed its width from wall to wall, the hilltop still appeared to move, but much more slowly. And if he walked even farther and repeated the experiment, the movement was smaller still. Venture far enough, he discovered, and there was no perceptible shift at all.

He made an entry in his notebook: The amount the hill moves depends on its distance from the observer. He had discovered the phenomenon called parallax.

Returning to the village, where the hill was closest and the effect was most pronounced, he measured the separation between the canyon walls and began to sketch out a picture:

The width of the canyon and the line of sight from each canyon wall to the center of the hilltop formed an imaginary triangle. Using a surveying instrument, he could measure the two angles at the triangles base. Then, using what he had learned in school about the rules of trigonometry, he calculated the height of the trianglethe distance from the center of the baseline to the apex, from the village straight across the impassable badlands to the hilltop. By this measure, it was ten canyon widths away. It was still impossible to walk there, but it was comforting to know the distance. The world seemed a little tamer.

Next page