SEARCHING

THE STARS

SEARCHING

THE STARS

THE STORY OF

CAROLINE HERSCHEL

MARILYN B. OGILVIE

I would like to dedicate this book to my four granddaughters, Keely Holzer, and Elizabeth, Molly and Caroline Ogilvie.

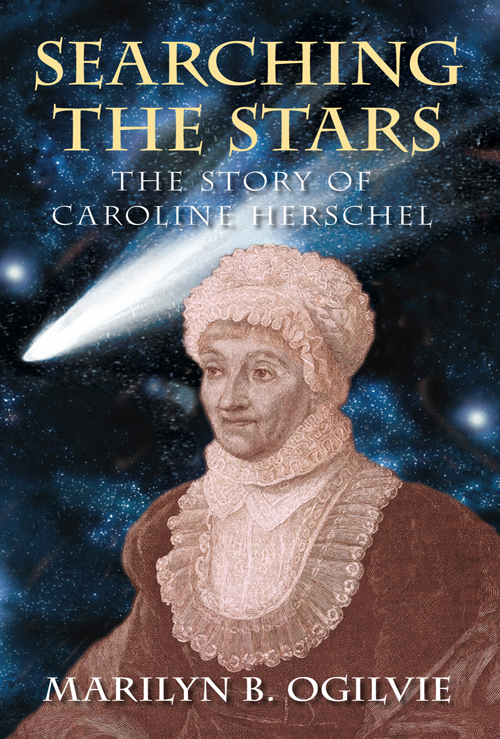

Cover Illustration: Caroline Herschel, courtesy of Mary Evans Picture Library

First published 2008

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

Marilyn B. Ogilvie, 2008, 2011

The right of Marilyn B. Ogilvie, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7546 2

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7545 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful for the support and encouragement of many people and institutions. I especially want to thank Richard Workman, Research Librarian at the Harry Ransom Research Center in Austin, Texas, and his staff for their assistance, and for permission to publish quotations and images from their Collection. I also appreciate the DVDs of the Herschel Archive which The Royal Astronomical Society provided. I am very gratified for the encouragement of colleagues in the History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries, and especially to Dr Kerry Magruder for his help with the images. I appreciate the support of Debra Engel, Associate Dean of Public Services, University of Oklahoma Libraries. Special kudos also go to Starla Doescher, Head of Acquisitions, University of Oklahoma Libraries, who was intrepid in following up on orders. I am also grateful to Patricia Cone for reading the completed manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

A woman in the shape of a monster

a monster in the shape of a woman

the skies are full of them

a woman in the snow

among the Clocks and instruments

or measuring the ground with poles

in her 98 years to discover

8 comets

she whom the moon ruled

Like us

levitating into the night sky

riding the polished lenses

Galaxies of women, there

doing penance for impetuosness

ribs chilled

in those spaces of the mind

An eye,

virile, precise and absolutely certain

from the mad webs of Uraniborg1

encountering the NOVA

every impulse of light exploding

from the core

as life flies out of us

Tycho whispering at last

Let me not seem to have lived in vain

What we see, we see

and seeing is changing

the light that shrivels a mountain

and leaves a man alive

Heartbeat of the pulsar

heart sweating through my body

The radio impulse pouring in from Taurus

I am bombarded yet I stand

I have been standing all my life in the

direct path of a battery of signals

the most accurately transmitted most

untranslatable language in the universe

I am a galactic cloud so deep so

involuted that a light wave could take 15

years to travel through me And has

taken I am an instrument in the shape

of a woman trying to translate pulsations

into images for the relief of the body

and the reconstruction of the mind.

Adrienne Rich

Planetarium. Thinking of Caroline Herschel, 17501848,

astronomer,

Sister of William; and others.

WHO WAS CAROLINE HERSCHEL?

Caroline Herschel has been characterized by some as an extension of her astronomer brother, William Herschel (17381822) and by others as an unappreciated, misunderstood, and creative astronomer in her own right. Either extreme gives an incomplete picture of Herschel. The poet Adrienne Rich proposed the latter scenario. Viewed through her own twentieth-century feminist eyes in her poem, Planetarium, Rich evoked a Caroline Herschel overlooked by history who stood in the snow/among Clocks and instruments/or measuring the ground with poles. Struggling with adverse conditions, she valiantly observed, took measurements, and recorded data. Rich complained that Caroline was denied credit for her discoveries because of her sex, and attempted to rescue her reputation in her poem.2 When evaluating the contributions of Herschel, it is tempting to allow our contemporary ideas to dictate the significance of an eighteenth/nineteenth-century woman. However in rejecting what historian of science David B. Kitts calls the terminal fallacy (viewing the past through present biases) it is equally unacceptable to espouse the opposite view, that Herschel got more recognition than she deserved because she was dependent on William for her astronomical accomplishments. There has been a decided shift in emphasis among feminist historians as they attempt to make Caroline Herschel an iconographic woman in science through downplaying her role as her brothers helper and stressing her independent achievements. Claire Brock in her 2007 biography of Caroline Herschel has attempted to rehabilitate Herschel by stressing her ambitions and her desire to become independent. Although this reinterpretation is valuable in breaking down biases regarding scientific women, it is important not to overstate the case. Herschels contributions to the enterprise of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century astronomy are so significant that overstatement, the retelling [of] womens stories to make them conform with modern ideals,3 is not only unnecessary, but undesirable. Through her collaboration with William, Caroline was crucial in creating his reputation, and together they influenced the course of astronomy. It was Caroline who converted the raw data into publishable, accurate astronomical knowledge. Her cataloguing skills were vital, and her attention to detail unsurpassed talents that William did not possess. Without understanding the construction of the heavens, it would have been impossible for Caroline to sort data, catalogue them, and make them available so that Williams reputation as a major eighteenth-century astronomer was assured. Although Carolines independent discoveries are also important, she seldom had time to pursue them because she was so involved in Williams enterprises.

HOW DO WE KNOW ABOUT CAROLINE HERSCHEL?

Thanks to the Herschels habits of keeping diaries, letters, and journals, there is a considerable amount of information available on Carolines life and work. The Royal Astronomical Society holds many of the Herschel manuscripts; J.R. Bennett listed them in the Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society 85 (1978). It is possible to obtain the information in the manuscripts by purchasing a DVD or microfilms from the Society. The Royal Society possesses a large collection of the correspondence of John Herschel, including some letters to Caroline as well as letters written by her. Other primary sources are located in Austin, Texas at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas. These papers include her autobiographies which she wrote twice, once in the 1820s for her youngest brother Dietrich and again in the 1840s for her nephew and his wife (John and Margaret Herschel). The first autobiography stops at 1788, the year William married, while the second finishes in 1782, the year brother Dietrich ran away to London. Since these autobiographies were written long after the events occurred the first when she was in her seventies and the second when she was in her nineties the two accounts vary slightly. Carolines written work was filled with creative spelling in English, and this biography retains her spelling or that transcribed by the sources. Invaluable to any work on Caroline Herschel is Michael Hoskins edited and transcribed version of these two autobiographies. Additional manuscripts sold at the same auction by Sothebys in London on 4 March 1958 are scattered throughout the world. Many of the Ransom Center manuscripts as well as numerous others were microfilmed before they were dispersed and may be consulted at the British Library.