For my quiet, clever family and for Austin & Paul, and the quiet, clever families they left behind.

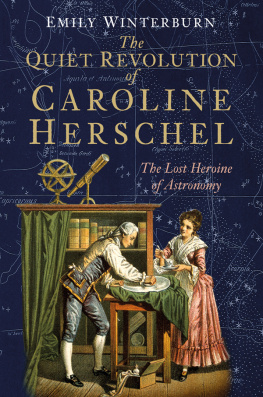

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

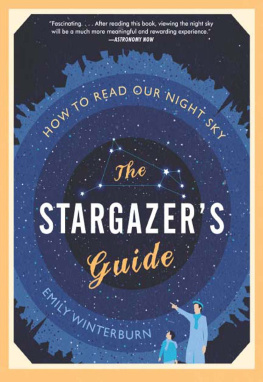

Emily Winterburn, 2017

The right of Emily Winterburn to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8651 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

PREFACE

T his book has been a long time in the making but is, I think, the better for it. I was first introduced to the Herschels back in around 1999 when the curator of astronomy at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, Maria Blyzinsky, showed me around the stores, talking me through the collections I was soon to take over. Piled up, I remember, in the middle of the floor in the basement to Flamsteed House (in the cellars of the former hunting lodge on which the observatory was subsequently built) were a number of acid-free conservation grade cardboard boxes. Inside those boxes treasure!

The boxes contained the contents of two cabinets that had once belonged to the Herschel family. Three generations had used them as a set of handy drawers, depositing parts of half-finished experiments, lenses, mirrors, coloured glass, a pin cushion, a pair of small scissors. The boxes contained all manner of bits and bobs, invitingly hinting at this familys peculiar mix of domestic and scientific life; providing questions, if not yet answers, about how science and family life might have once coexisted side by side down the generations.

The Herschel family, I knew, were famous. They had achieved many great things, but what those were, or which of the plethora of Herschels had achieved what, I was not quite sure. And so I set about finding out and from that learning process eventually grew a PhD and, later still, this book.

Where research for my PhD ended and the research for this book began is a grey area, but all of it has been fascinating. I have been to some amazing places. I have talked to people all over the world at conferences, but also in conversation, the moment anyone has shown the slightest bit of interest in the Herschels. I have investigated numerous archives, often to be found in beautiful libraries. I even met the Herschels modern-day descendants, who very kindly put me up for a week and allowed me to nose around their private family archive uncovering all kinds of material that previous generations of historians, archivists and collectors had left behind.

From this mass of material from all the letters, diaries, artefacts and other ephemera stories emerged that seemed to not quite tally with the existing accounts I had by this stage already read. Perhaps my background in physics made me see things differently. All that time spent studying physics and always being one of the only girls; feeling that my voice was quieter, less confident, less certain than my male peers perhaps that gave me a different perspective. Certainly the picture of Caroline Herschel these sources painted was very different to what I had read in biographies and articles on this pioneering woman of science.

Caroline Herschel wrote a lot about her life. She kept diaries, accounts and an observing book. She also wrote extensively about her life, especially her early life, in two autobiographies written for relatives in old age, and supplemented these with anecdotes in her letters. Much of the time this was in response to direct questions: people wanted to know how she had become an astronomer when so few women were visible in that field; they wanted to know about her and her background and she wanted to tell them a good story.

In her letters, and especially in her autobiographies, Caroline was very careful to present herself in a particular way. When she put her mind to it, the image she presented of her life and her path to success was that of an innocent, wide-eyed, but put-upon heroine. She was a passive but grateful recipient of good fortune. These accounts were, after all, written in the years when the Grimm brothers were collecting and recording their fairy tales. Heroines in those stories were kind and gentle, willing participants complicit in their own subjugation. Caroline, as ever, was quick to pick up on the prevailing mood and to weave those images into her own accounts of her life. At one point in those stories, she even referred to herself as the Cinderella or Ashenbrthe of the Family (being the only girl).

To an extent, those fairy stories and the portrayal Caroline adopted from them reflected the real-life experiences of women, and especially low-status women, in eighteenth-century Europe. Women were expected to fit in with men, to have access to education only if they had a male relative who chose to allow it. They were expected to stay at home, cook, clean and raise children while their brothers, fathers and husbands went out into the world. They were expected to accept their fate quietly, their only hope of escape to be found in meeting a prince or, at the very least, a wealthy man, and to marry him.

Caroline grew up in the part of the world from which the Brothers Grimm collected most of their stories. Those stories came out of a folk tradition with which Caroline would have been familiar and so her adoption of some of the caricatures in her accounts of herself and her life is understandable. What has always seemed stranger to me is that historians have also often adopted these fairy-tale caricatures when talking about Carolines life. She is very often, even now, described as astronomys Cinderella. Her mother, meanwhile, is cast with annoying regularity as the wicked stepmother, while William gets to be her saviour prince.

Perhaps Carolines mother is often presented in such damning terms because her story otherwise lacks any real tangible enemy. Although Caroline was very much a woman of her time, faced with all the barriers to education and scientific institutions and public debate which that entailed, she was never victim to any direct attacks, as some women were. Her story contains no Big Bad Wolf. Overall, most of her fellow astronomers and the many other scientific individuals she came across were welcoming and encouraging. In a sense, her enemy was more abstract. While no one individual insisted that she stay quiet or be kept down, just simply by virtue of being a woman, fellow practitioners of science and the wider world were less ready to believe in her abilities and accept her claims. That she found ways around this obstacle is very much to her credit, and an essential although often overlooked part of her story.

Accounts of Caroline to date tend to have taken her fairy-tale depiction of herself and her family at face value. They have overlooked her struggles for recognition in the absence of any overt force putting her down. Most puzzling of all, though, is the uncritical acceptance of her ten missing years. The years 1788 to 1797 are entirely absent in Carolines accounts of herself. They are gone deliberately destroyed and yet they were, in many ways, her most significant years in terms of work. The missing period dates from the year her brother William married to the year she moved out of her brothers home and they are

Next page