PUBLISHED TITLES IN THE GREAT DISCOVERIES SERIES

David Foster Wallace

Everything and More: A Compact History of

Sherwin B. Nuland

The Doctors Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever, and the Strange Story of Ignc Semmelweis

Michio Kaku

Einsteins Cosmos: How Albert Einsteins Vision

Transformed Our Understanding of Space and Time

Barbara Goldsmith

Obsessive Genius: Marie Curie: A Life in Science

Rebecca Goldstein

Incompleteness: The Proof and Paradox of Kurt Gdel

Madison Smartt Bell

Lavoisier in the Year One: The Birth of a New Science in an Age of Revolution

George Johnson

Miss Leavitts Stars: The Untold Story of the Forgotten

Woman Who Discovered How to Measure the Universe

David Leavitt

The Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer

William T. Vollmann

Uncentering the Earth: Copernicus and The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres

David Quammen

The Reluctant Mr. Darwin: An Intimate Portrait of Charles Darwin and the Making of His Theory of Evolution

Richard Reeves

A Force of Nature: The Frontier Genius of Ernest Rutherford

FORTHCOMING TITLES

Daniel Hofstadter on Galileo

Lawrence Krauss on the Science of Richard Feynman

General Editors: Edwin Barber and Jesse Cohen

BY MICHAEL D. LEMONICK

The Light at the Edge of the Universe

Other Worlds: The Search for Life in the Universe

Echo of the Big Bang

MICHAEL D. LEMONICK

The Georgian Star

How William and Caroline Herschel Revolutionized Our Understanding of the Cosmos

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright 2009 by Michael D. Lemonick

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lemonick, Michael D., 1953

The Georgian star: how William and Caroline Herschel revolutionized

our understanding of the cosmos / Michael D. Lemonick.

p. cm.(Great discoveries)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-393-07208-2

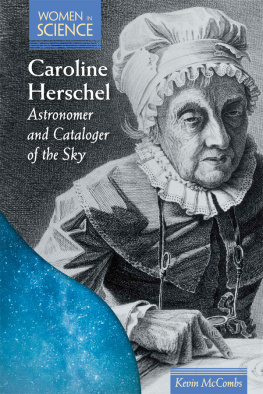

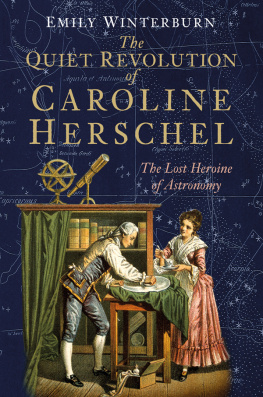

1. Herschel, William, Sir, 17381822. 2. Herschel, Caroline Lucretia,

17501848. 3. AstronomyHistory19th century. I. Title.

QB35.L36 2009

520.92'2dc22

[B]

2008029820

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

For Rita and Myer Bernstein,

who have been like parents to me

The Georgian Star

Contents

F ew people today encounter the true night sky. The relentless glow of city, suburban, and even rural lighting, scattered and reflected by pollutants drifting through the stratosphere, tends to wash out all but a few dozen of the brightest stars, a couple of planets, and the moon. If you travel to somewhere remote, however, like the mountaintops in Arizona or northern Chile, where professional astronomers do their work, the effect can be shocking. The sky seems to overflow with stars. Theyre like tiny, perfect jewels set in a velvet-black backdrop, bisected by the luminous ribbon of the Milky Way. The constellations most of us know only from textbooks and planetarium shows are easy to pick out. You may not be convinced that the Big Dipper resembles a bear, as the Greeks and Romans believed, or that the stars of Orion mark out the shape of a hunter. But you can easily believe theyre pictures of something. The stars are so bright and so numerous that they feel almost as physically present as the mountains and trees. For all of human history, until Edison invented the electric light, this is how every person on Earth experienced themeven in preindustrial cities the size of Paris and New York.

Its no wonder that our ancestors were in literal awe of the skies, and that virtually every civilization saw them as a manifestation of divinity, a place where gods must live. Its also no wonder that Galileo got into such trouble with the Catholic Church for challenging the official view of the heavens. Seen through a telescope, he said, the moon was no supernaturally perfect sphere but rather a small, barren world complete with a mundane topography of craters and craggy peaks. Over time, Galileo, Kepler, Newton, and others managed to supplant the divine picture of the cosmos with a physical one. But instead of diminishing the awe that humans feel when they encounter the heavens, these natural philosophers simply redirected it. Equally marvelous to the legend of Orion the Hunter are the facts that stars are actually gigantic balls of gas, thousands of times bigger than Earth and undergoing controlled thermonuclear explosions that last for billions of years; that the cosmos is populated not just with stars but with black holes, quasars, neutron stars, and that its filled with a mysterious dark matter and even more mysterious dark energy; that the entire universe sprang into being 14 billion years ago in a single, colossal event that we call the Big Bang.

None of these discoveries would have been possible, or even conceivable, without the development of telescopes much more powerful than anything Galileo had. But just as important, astronomers had to come up with new ways of using their instrumentsof teasing out the heavens subtle secrets in a systematic way. This required not just simple observations but also leaps of intuition to interpret what they saw. They had to concoct theories of how the universe was organized and how it operated and then go back to the telescope to see if they were right. Most of all, they needed as much data as they could get their hands on. It was extraordinary, breakthrough science, for example, when the Swiss astronomer Michel Mayor found the first planet orbiting a star other the sun, in 1995. But that single example was nearly useless at answering the question most people cared about: how many solar systems exist in our galaxy, and how many of them are likely to include a planet like Earth? Today, with more than two hundred so-called extrasolar planets known, the answer to that mystery is a lot closer. But more theorizing and painstaking fieldwork are still necessary.

More than anything, modern astronomy depends on the ability to organize enormously complicated jumbles of data collected from the sky. In the middle of the eighteenth century, with the Enlightenment in full flower, nobody had quite figured out how to do so. All of that would change within a few years, thanks to an astronomer who did not arise from the ranks of gentlemen who dominated science at the time but who came seemingly out of nowhere. He had little in the way of formal education. What he did have was a nearly boundless supply of curiosity and drive fostered by a talented family, particularly by his sister and professional partner, Caroline. And if his sense of wonder ever flagged, he only had to look up into those truly dark skies.

O ne evening in the spring of 1781, Mr. William Herschel, of Bath, England, presented a report to the gentlemen of the citys Literary and Philosophical Society. Mr. Herschel had joined the society as a charter member about a year and a half earlier. From the start hed churned out scientific papers at a prolific rate, on eclectic topics ranging from the purely speculative and philosophical to the concrete and practical. His first report, for example, concerned the growth of corallines, a form of algae that accumulates on coral reefs and rocks along the seashore. Among those that followed were papers titled On the Existence of Space, The Question, Whether a Knowledge of the Classic Authors in Their Own Languages, Is Essentially Necessary to One Who Would Write English with Elegance and Perspicuity, Considered, and Experiments on Prince Ruperts Glass Drops.