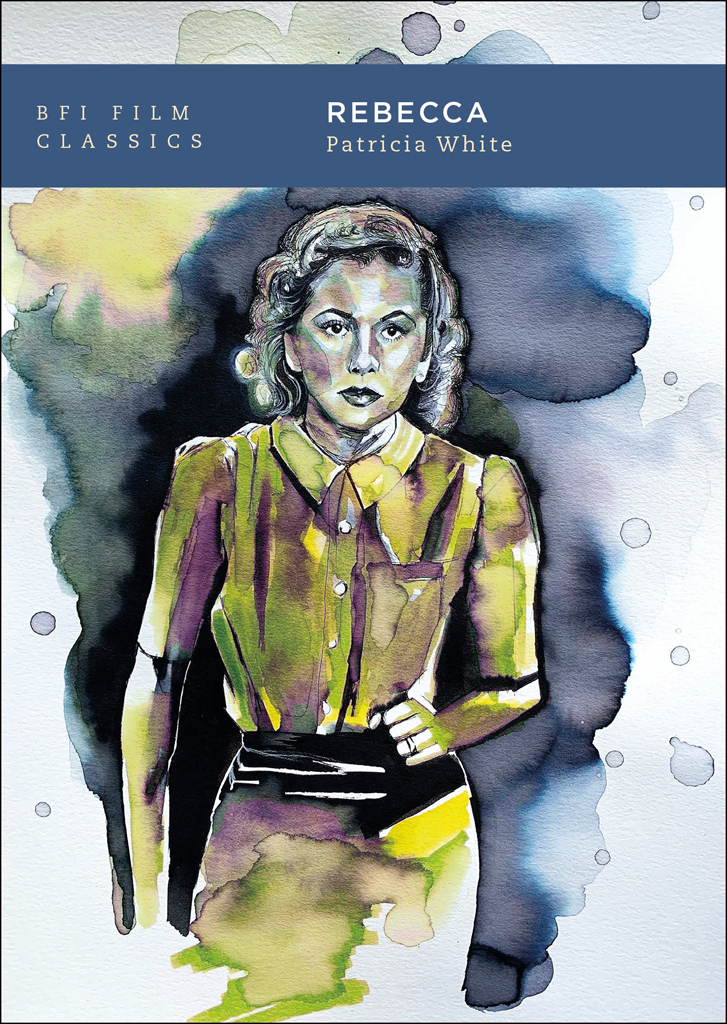

BFI Film Classics

The BFI Film Classics series introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the films classic status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the authors personal response to the film.

For a full list of titles in the series, please visit

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/series/bfi-film-classics/

For my mom, Donna J. White (19342019)

THE BRITISH FILM INSTITUTE

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA

BLOOMSBURY is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2021 by Bloomsbury on behalf of the

British Film Institute

21 Stephen Street, London W1T 1LN

www.bfi.org.uk

The BFI is the lead organisation for film in the UK and the distributor of Lottery funds for film. Our mission is to ensure that film is central to our cultural life, in particular by supporting and nurturing the next generation of filmmakers and audiences. We serve a public role which covers the cultural, creative and economic aspects of film in the UK.

Copyright Patricia White 2021

Patricia White has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as author of this work.

For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. 6 constitute an extension of this copyright page.

Cover artwork: Federica Masini

Series cover design: Louise Dugdale

Series text design: Ketchup/SE14

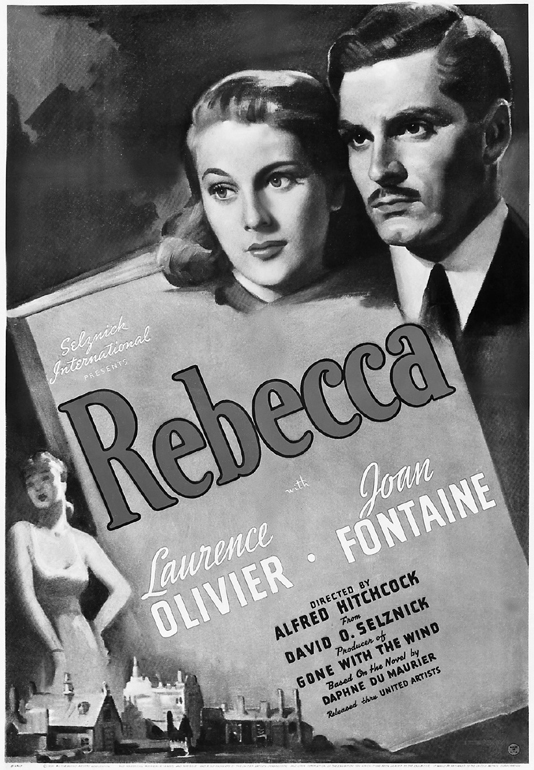

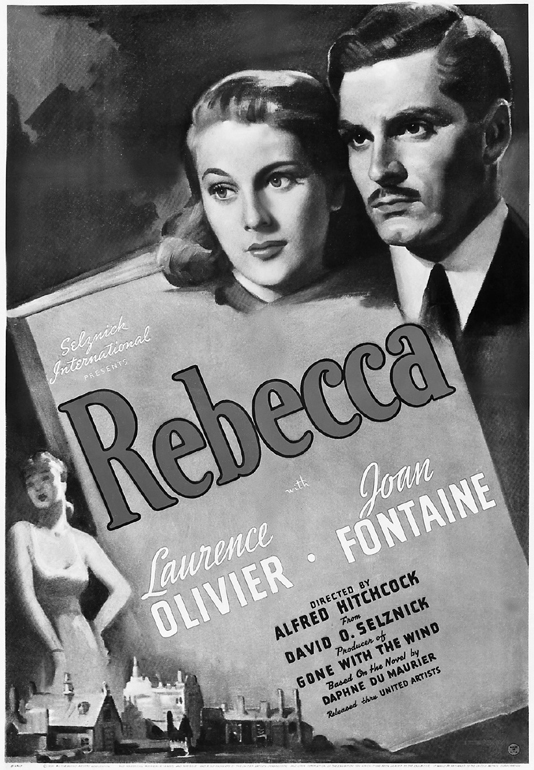

Images from Rebecca (Alfred Hitchcock, 1940), Selznick International Pictures; Wuthering Heights

(William Wyler, 1939), Samuel Goldwyn, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: PB: 978-1-9112-3943-7

ePDF: 978-1-9112-3945-1

ePUB: 978-1-9112-3944-4

Produced for Bloomsbury Publishing Plc by Sophie Contento

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com

and sign up for our newsletters.

Contents

Ive written about Rebecca before, and I am indebted to the many friends, family, colleagues and students who have accompanied and encouraged me on my many returns. Lisa Kennedy was my interlocutor throughout the writing, and I am deeply grateful for her editorial insight, unwavering support and generosity as a writer. Bakirathi Mani and Lara Cohen provided astute and timely writing-group feedback, and Amelie Hasties experience and creative counsel were invaluable at a crucial juncture. Thank you to the students in Women and Popular Culture and to Rachel Kabasakalian McKay for their insights. Lisa Cohens inscription on my Avon paperback of du Mauriers novel made me smile, and Rhona J. Berensteins work on the film led to new ideas and a lasting friendship. My debt to Tania Modleskis writing is evident throughout these pages, and Alex Dotys memory animates my tribute to Mrs Danvers. Christina Lane graciously shared her research and insights; I thank her for her rigorous and inspiring scholarship. My mom introduced me to Rebecca, and I miss watching old movies with her. My deepest gratitude goes to Cynthia Schneider and Max Schneider-White for their patience, encouragement and welcome distractions as I wrote during hard times in close quarters.

Researching the production of a classical Hollywood studio film promised rich opportunities for archival rummaging that were cut short in spring 2020 for pandemic mitigation. I want to thank the supremely organized archivists who accessed everything they could despite the closures: Nancy Kauffman and Lauren Lean at George Eastman House, Mary Huelsbeck at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, and Genevieve Maxwell at the Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. I am especially indebted to Cristina Meisner at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, which houses the vast Selznick Collection, for scouring the record for digitized material. I hope I am able to visit eventually. Special thanks to Mimi Muray Levitt, who in answering a permission request for Nickolas Murays glamour shot of Judith Anderson shared wonderful snapshots and her fathers eloquent tribute to her Aunt Judy.

I am grateful to Swarthmore College for its rare and sustaining intellectual community and for the support provided by the Eugene Lang Research Chair. Thanks to Karen Stetler and Liz Helfgott for the opportunity to contribute to the Criterion edition of Rebecca and to the great Molly Haskell for such a good time discussing the film.

As a film buff, I feel almost as much awe for the books in the BFI Film Classics series as for the films they are named after, and I thank series editor Rebecca Barden for facilitating my long-held dream to contribute. Is it mere coincidence that she shares her name with the films animating female force? Im especially happy to be part of the Bloomsbury relaunch, which is redefining the word classic by tampering with the canon. Sincere thanks to Sophie Contento, who secured stills from the BFI and expertly managed production during an exceedingly challenging time. To the anonymous readers, I express my deep appreciation for their support of this book.

She who writes about Rebecca the novel, the film, the phenomenon must reckon with an oddity enabled by its first-person point of view: the protagonist has no name, and the writer must decide how to refer to the character. The novel is so bound up with the question of (staking out) female/feminine identity that this lack is somehow appropriate. It can even go unnoticed. In the course of the story, the protagonist takes on a role that comes with its own name Mrs de Winter borrowed from a man. Yet she is not the (only) Mrs de Winter; the name is also borrowed from a woman. I has no fixed identity except in the present instance of discourse, as linguist mile Benveniste describes the pronoun and its companion, you. He calls this a very strange thing. A vast readership, largely of women, addressed by du Mauriers writing, became you. We became I. The strange drama of the shifter is encapsulated when the heroine declares: I am Mrs de Winter now.

In A Room of Ones Own, Virginia Woolf wrote amusingly of the experience of reading the work of a contemporary male novelist: But why was I bored? Partly because of the dominance of the letter I and the aridity, which, like the giant beech tree, it casts within its shade. Nothing will grow there. Woolfs I, a female I, is trickier, rhizomatic, it flickers between objective description and subjective inscription. While du Maurier may not write with Woolfs wit or feminist self-consciousness, she achieves a similar flicker effect.