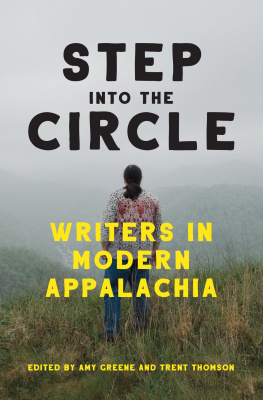

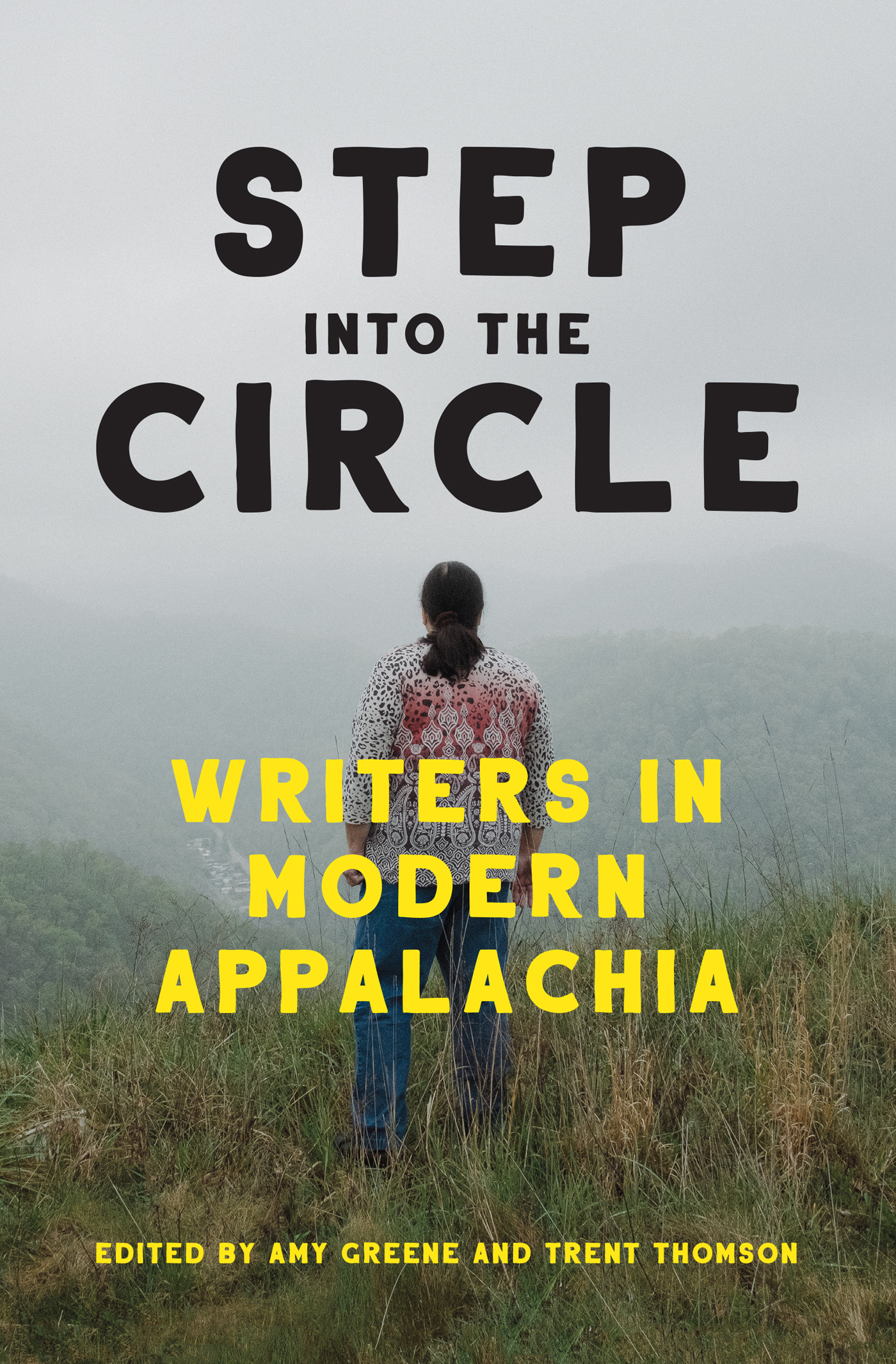

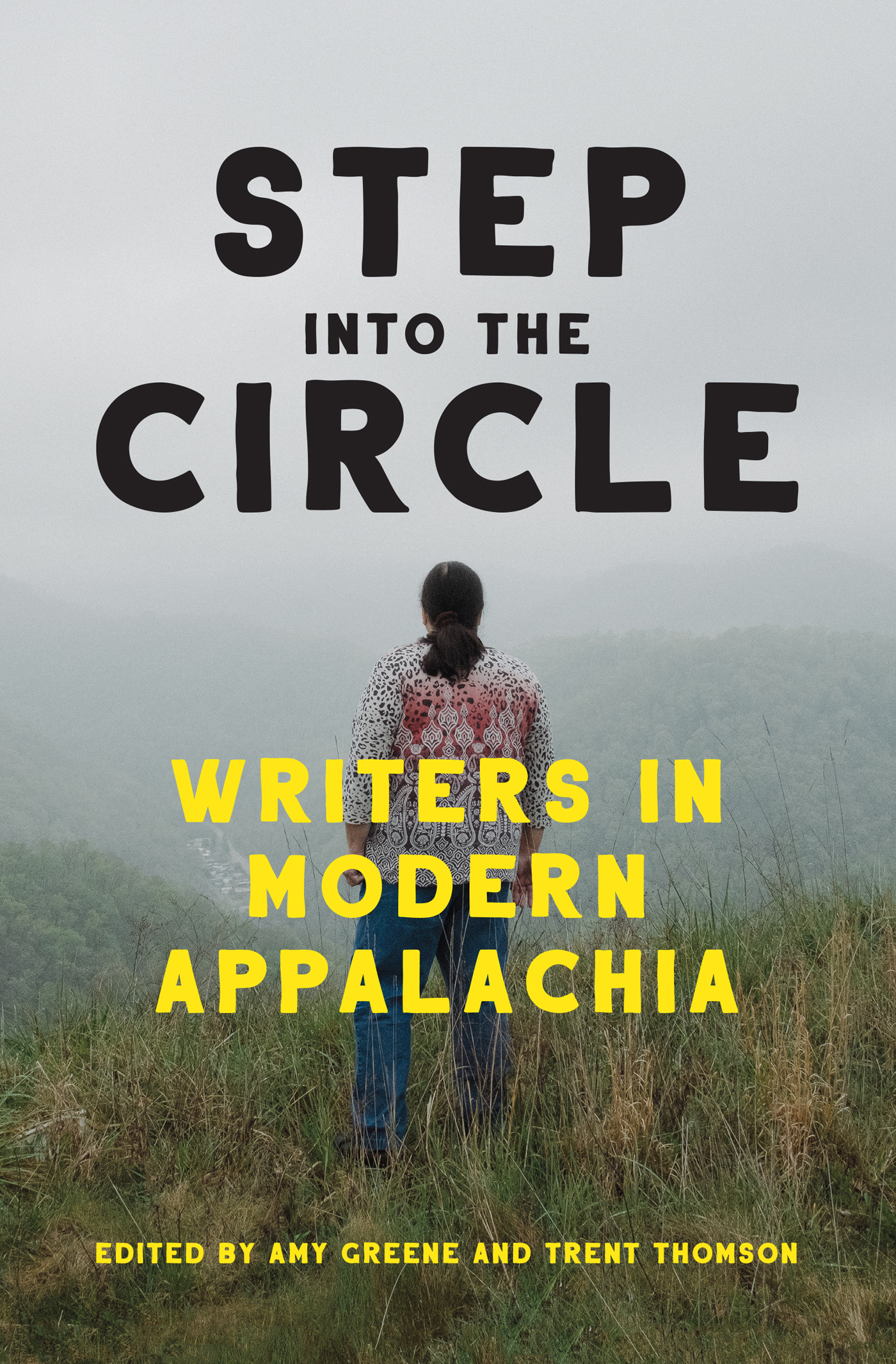

STEP INTO THE CIRCLE

STEP INTO THE CIRCLE

EDITED BY TRENT THOMSON & AMY GREENE

BLAIR

Copyright 2019 by Trent Thomson and Amy Greene

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Cover design by Laura Williams

Interior design by April Leidig

Blair is an imprint of Carolina Wren Press.

The mission of Blair/Carolina Wren Press is to seek out, nurture, and promote literary work by new and underrepresented writers.

We gratefully acknowledge the ongoing support of general operations by the Durham Arts Councils Annual Arts Fund and the N.C. Arts Council, a division of the Department of Natural & Cultural Resources.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019949131

Photos on and facing by Mallory Cash

Photo on by Shawn Poynter

A VISION

If we will have the wisdom to survive,

to stand like slow-growing trees

on a ruined place, renewing, enriching it

The abundance of this place,

the songs of its people and its birds,

will be health and wisdom and indwelling

light. This is no paradisal dream.

Its hardship is its possibility.

Wendell Berry

PHOTO BY WILL WARASILA

CONTENTS

AMY GREENE | PHOTOGRAPHS BY SHAWN POYNTER

SILAS HOUSE | PHOTOGRAPHS BY GUY MENDES & TANYA AMYX BERRY

KAREN MCELMURRAY | PHOTOGRAPHS BY SAM STAPLETON

WILEY CASH | PHOTOGRAPHS BY MALLORY CASH

AMY D. CLARK | PHOTOGRAPHS BY TIM C. COX & SHAWN POYNTER

AMY GREENE | PHOTOGRAPHS BY C. WILLIAMS & TASHA THOMAS

PATRICIA HUDSON | PHOTOGRAPHS BY SAM STAPLETON

DENTON LOVING | PHOTOGRAPHS BY ROBERT MORTON

ANNETTE SAUNOOKE CLAPSADDLE | PHOTOGRAPHS BY WILL WARASILA

JASON KYLE HOWARD | PHOTOGRAPHS BY MALLORY CASH

PHOTO BY WILL WARASILA

PHOTO BY SHAWN POYNTER

INTRODUCTION

AMY GREENE

W hen Trent and I came to the place we would name Bloodroot Mountain, twenty-one forested acres with a timber-frame barn, it had gone for years uninhabited. In the woods where we climbed up through the trees, sun reached the ground in nickels and dimes. The shagbark trunks were twisted in vines. There were no voices. There were only wet weather streams over rocks. There were only leaves turned over and over, sifted and sorted by the hands of the wind.

It was a place we had been before and never before. We have always known the landscape of East Tennessee, narrow valleys made of ridges and creeks, ringed in mountains formed five hundred million years ago, once flooded by an ancient sea, the shellfish that swam those waters now fossilized in a layer of limestone sediment. We wondered as we walked the property about ancestral memory, if a persons connection to home might be inborn.

When we moved into the barn that became our studio, I sat writing with the door open, watching doves peck in the grass growing between the paving stones and among the locust saplings that had invaded the garden. They would come to the threshold and peer inside, molting feathers. For so long, it had been their domain.

Wild things had made their nests in the woodstove. Hickory nuts stored over field mouse winters rolled out from under the pie safe into dark corners. Shed snake skins wrapped the iron bed legs. Up in the loft the floorboards were splattered white with the droppings of nesting swallows.

PHOTOS BY SHAWN POYNTER

I suppose not many would have looked at Bloodroot Mountain and envisioned a place to live and work, maybe because its harder somehow to see the beauty of the landscapes we know as we do ourselves, the geographies that have toughened our feet. Home is sometimes too familiar. Its like when you hold your hand so close to your face that it blurs out of focus. The first time we encountered our land, Trent and I sensed more than saw what was possible. We glimpsed light in the depths of the ponds murk. We heard the lullaby creak of the barn boards. We considered that ginseng might grow on the steep, north-facing slopes. We began to dream that art could be formed out of the green silence.

PHOTOS BY SHAWN POYNTER

We asked ourselves, what can be done here? Could this be a school of thought, an incubator for ideas? Could it be a beacon for progress in the wilderness? Could it be a quiet haven where artists find loud voices? The answer is always yes, if we make it so.

Yes, Bloodroot Mountain can be such a place. Yes, Appalachia can be such a place. It takes only seeing whats before us. It was the writer Lee Smith who first showed me. In my early twenties, I read her novel Oral History and thought, I can write about my people and my place. We and these mountains are worth something. It has largely been writers like Smith who have told the rest of the nation, Theres something going on here that counts. They have said, Look at our natural resources. Lets protect them. Look at our young. Lets lift them on our shoulders. The ten writers featured here, by their words and deeds, have built a foundation not only for other writers, but for a whole culture to rise up on.

I think of all writers as seers, but perhaps Appalachian writers in particular, growing up in the hollows and coves, observers of the pasture hills and valleys, of our families across the supper table and our neighbors on their way to work.

It may be harder to see whats most familiar to us, but maybe the opposite is also true. You see more when youre invisible, when youve been overlooked. Maybe its easier to dream up visions from the margins.

Next page