HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT

Boston New York 2011

Copyright 2011 by Andrew Westoll

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Westoll, Andrew.

The chimps of Fauna Sanctuary : a true story of resilience and recovery / Andrew Westoll.

p. cm.

Summary: "A journalist and primatologist tells the remarkable story of thirteen chimpanzees

and the people who care for them at Fauna Sanctuary as they recover from the trauma of years of

use as laboratory subjects and learn how to trust humans and, more importantly, how to be chimps

again"Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-547-32780-8 (hardback)

1. ChimpanzeesConservation. 2. ChimpanzeesBehavior. 3. Animal rescue.

4. Wildlife recovery. 5. Wildlife refuges. I. Title.

QL 737. P 96 W 379 2011

636.9885dc22 2010049783

Book design by Melissa Lotfy

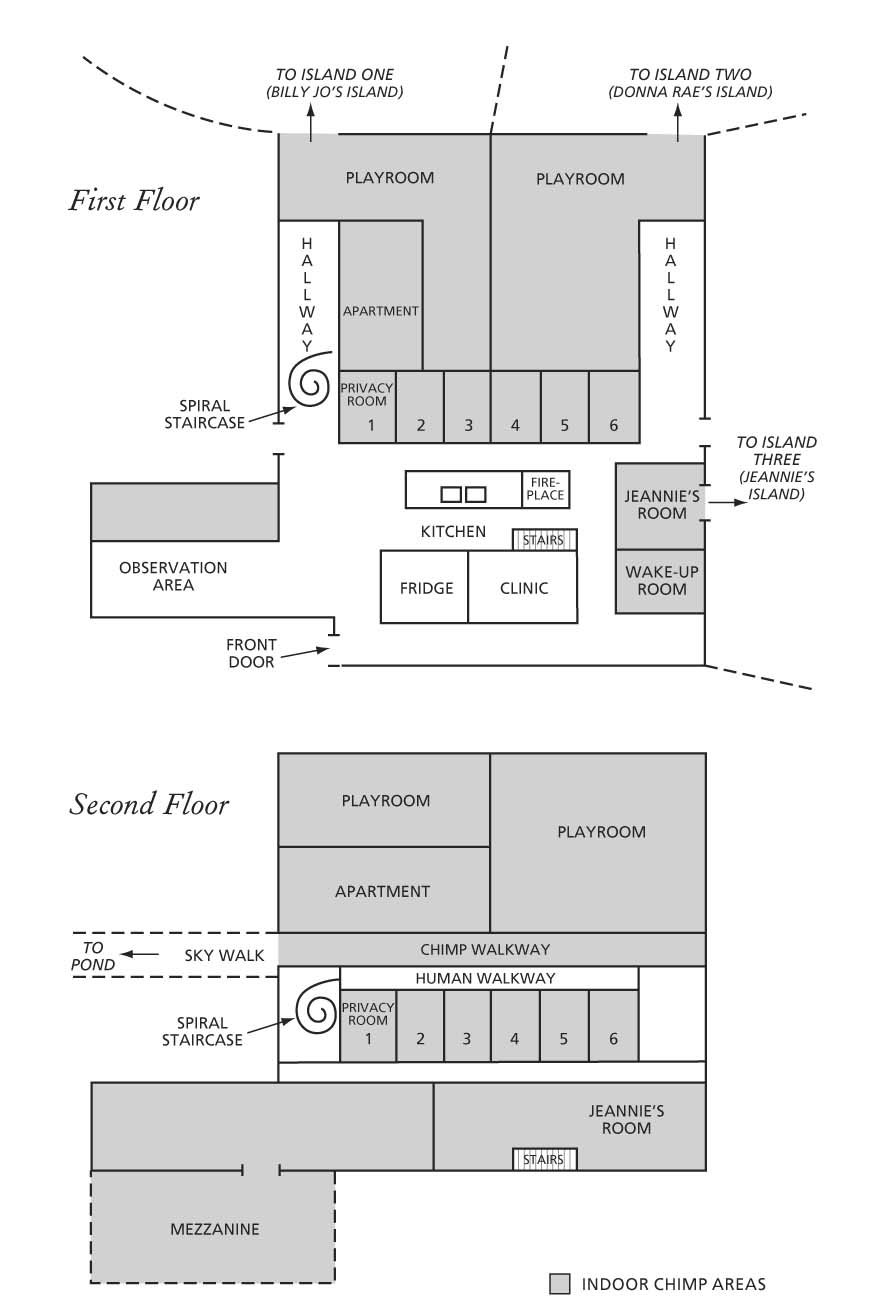

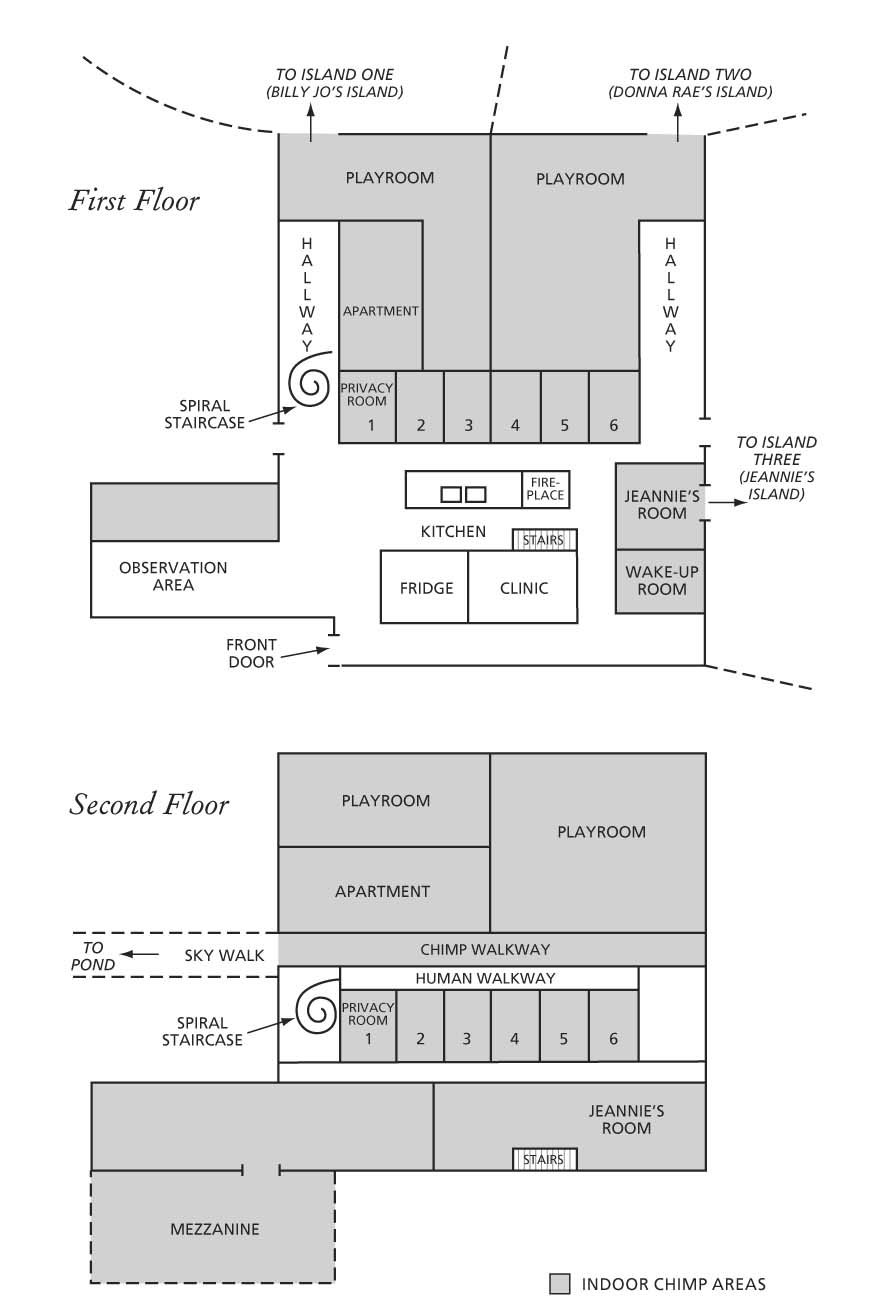

Floor plan by Mapping Specialists, Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Tom,

and all of us great apes

Resilience is more than resistance, it's also learning to live.

BORIS CYRULNIK , Un Merveilleux Malheur

What kind of animals are we?

FRANS DE WAAL , The Age of Empathy

Contents

Chimphouse Floor Plan

1. Full-Moon Week

2. Zihuatanejo, Quebec

3. Our Disquieting Doubles

4. Blueprints of a Dream

5. The Cage Hospital

6. Toby and the Hoodlums

7. Operation Cucarachas

8. Tales from the Campfire

9. The Pressure Washer

10. Inner Sanctuary

11. War Memorials

12. The Haunted

13. The End of an Era

Afterword

How You Can Help the Chimps

Further Reading

Acknowledgments

The Chimphouse

Chapter 1

FULL-MOON WEEK

I am not interested in why man commits evil.

I want to know why he does good.

VCLAV HAVEL

Chimp Art

"S MELL MY PHONE, " says Gloria Grow as I climb into her Jeep at Montreal's Trudeau Airport. She guns the engine and hands me her cell phone. "Go on. Smell it."

These are Gloria's first words to me in person. We've already had two long phone conversations, between my home in Toronto and her farm in Quebec. By the end of those talks she'd invited me to move in with her family and write a book about them. But at no point did Gloria seem like the sort of person who would ask a virtual stranger to smell her phone.

There is nothing peculiar about the cell, a standard-issue flip phone. But upon closer inspection I notice a constellation of little divotsare they bite marks?punched into the bright pink casing. I look at Gloria. She is frowning. A construction detour has sent us in circles.

"Go on," she says again. I raise the phone to my nose.

I smell a swamp. Rotten fruit. Fecal matter. The reek of a tropical jungle.

"I love it," I say.

"Me too. Richard got me pink. I hate pink. But now I can't bear to throw it out. Open it."

I flip the casing open, and the LCD comes to life. But instead of showing an orderly sequence of numbers and icons, the screen is a mess, a muddy squelch of black ink. The phone has been crushed, or chewed, beyond repair.

"These roads!" says Gloria, making her third consecutive left-hand turn. Then she reaches over and presses her thumb into the phone's screen. The inky cloud morphs into kaleidoscopic rainbows.

"Isn't that beautiful?" she says without looking over. "It's like chimp art."

I fiddle with the cell phone, making a few of my own psychedelic impressions on the screen. As we descend an exit ramp to nowhere, Gloria sighs. She reaches over and tears the phone from my hand. Closing her eyes, she presses the phone to her nose and inhales deeply.

"They only gave it back to me yesterday."

Cat Lady

T HIS IS the story of a family of troubled animals who live on a farm in the French Canadian countryside. It is the story of how these animals came to be so troubled and how they are slowly becoming less so, in their own particular ways, through the actions of a small group of people led by Gloria Grow.

When I say these animals are a family, I don't mean they share a mother or father or brothers or sisters (although some of them surely do). They are a family in the sense that any group of beings who have lived together, suffered together, and triumphed together becomes a family. They are related in the way we are all related to one another, and here lies the source of their great misfortune.

I first contacted Gloria in 1998, when I was a college biology student. I wrote to inquire about volunteer opportunities at the Fauna Foundation, the sanctuary for rescued animals that Gloria had recently founded with her partner, a veterinarian named Richard Allan, on their 240-acre hobby farm near Chambly. The foundation had recently been all over the local, national, and international news because it had just become the permanent retirement home for a very special group of chimpanzees.

At the time I was one of thousands of young biology students who, inspired by the usual suspects (Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, the breathless David Attenborough), would have done just about anything to get a job either working with or studying great apesthe orangutans, gorillas, bonobos, and chimpanzees most of us have seen only in a zoo or in the pages of National Geographic. So when I first heard of Fauna, I couldn't believe it. The place sounded like my own personal Shangri-la. Imagine: an opportunity to experience chimpanzee behavior in the flesh, just a short drive from Canada's most sophisticated and seductive city, thereby removing the need to fund a kamikaze trek to the remote Central African rainforest (something I, at a much younger age, had briefly considered until I did a little reading and learned what the "civil" in "civil war" actually meant).

I didn't know why the chimps had been shipped to Fauna from their home in New York State. I knew nothing of what they'd been subjected to there or of the struggles each one faced in adjusting to retirement in Canada. All I knew was I wanted to work with them. Looking back, I find it unsettling how selfish my curiosity really was.

Unfortunately, life got in the way, and the volunteering idea came to nothing. Soon after that I was offered a dream job of a different sort. After graduating, I spent a year in the jungles of Suriname, just north of the Amazon rainforest, studying wild troops of brown capuchin monkeys. Though they're no great apes, capuchins are known as the chimpanzees of the New World for their intelligence and primitive forms of tool use. I was employed by the University of Florida, funded by the National Science Foundation and the Leakey Foundation. My dreams fulfilled, my interests served, the chimpanzees of Fauna became a distant memory.

Fast-forward more than a decade, then, throw in a career shift from scientist to writer, and here I am with Gloria, searching for a way out of Montreal, struggling to correlate the embarrassing mental image I'd had of her with the real-life version sitting next to me.

The stereotype of the woman who dedicates her life to rescuing animals is a surprisingly powerful cultural image. Often referred to as the Crazy Cat Lady, but by no means limited to felines, she shuffles around in moldy slippers, the backs of her hands are raked with claw marks, and at any moment a minimum of four living creatures are buried somewhere in the folds of her robe. This woman is a walking menagerie of frumpy disillusionment, in desperate need of the unconditional love only an animal can provide. And although that image is a cruel exaggeration, I was half-expecting some variation on it when I climbed into the Jeep and finally met Gloria, more than ten years after my first attempt.

Next page