READING GREAT-GRANDFATHER'S

1868 DIARY FOR HIS STORY

by

Charlie Dickinson

COPYRIGHT PAGE

Copyright 2023by Charlie Dickinson under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license. Some rights reserved. This book may be reproduced in print and digital formats when the author is acknowledged, the text of the book is unchanged, and copies are not used commercially. The language of the applicable license deed is available in full at http://www.creativecommons.org.

Published in the United States by Ch. Dickinson, Portland, Oregon

Publisher's Cataloguing-in-Publication

Dickinson, Charlie

Reading Great-grandfather's 1868 Diary for His Story--1st ed.--Portland

Or.:Ch. Dickinson, 2023.

eISBN: 978-1-7366893-4-9

1. Dickinson, Charles Edward--1850--1934--Diaries

2. St. Louis MO--1868--Personal Narratives

3. St. Louis MO. 4. Biography.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

FIRST EDITION

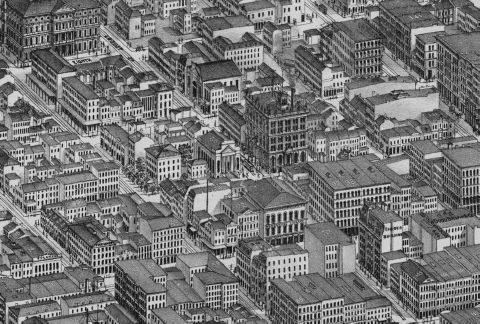

Charles Edward's St. Louis neighborhood

circa 1868.

INTRODUCTION

A history of events 150 years ago might, or might not, engage readers. For despite a historians best efforts to bring the past alive, its not hard to find distance from whats written. Readers might wonder where the historians reputation stands in the field of inquiry. They might quibble about the writing: its appeal or shortcomings. And they might decide a history of the Choctaw Nation fighting for the Confederate cause in the Civil War didnt account for that much on the national stage, and their time might be better spent reading other histories.

Although I am not a historian, Ive had the opportunity to look at events from 150 years ago through a special telescope. Some years ago, a diary written by my great-grandfather Charles Edward was handed down to me. A book of daily entries, it starts January 1, 1868. The diarist is seventeen and lives in St. Louis, Missouri, where he attends a preparatory school for young men, the Academy at Washington University in St. Louis. Being away from his hometown of Dubuque, Iowa, he stays with his Uncle William and Aunt Evelina Dickinson. He walks thirteen blocks to school, or about one mile each way.

I would read the daily entries with the spur of interdependence: If Charles Edward hadnt lived, I wouldnt exist. But the general reader doesnt have that descendant connection, so I knew my eventual task was to tell a coming-of-age story, if sketchy, comprising daily grains of thought. If with a close reading of the text and supporting research, I could summon an understanding of my great-grandfathers seventeenth year and where hed go, then I might have something more than family tree highlights, something of one durable life in the American story.

When I picked up this slim book of neatly pencilled entries and began reading, I was struck by the discipline and regularity of Charles Edwards life. He always rose mornings between five and six. He took pride in assiduously minding his priorities: chores for Uncle and Aunt, school and study, church meetings, and socializing with other people. More than seventy persons are mentioned in the diary. In brief, the reader senses this is an outgoing young man living an exemplary life with strong bourgeois values. We gather he is well on his way to more education and a career as a professional, much like his older brother William Pliny, a dentist practicing in Joliet, Illinois.

But things go differently, go badly for Charles Edward. He leaves St. Louis in the summer of 1868 with a personal dream waylaid and knowing a death in the family, foreshadowed in the diary, has happened. Rather abruptly, he quits the diary after five months of entries, in May 1868.

It would be easy in a timeless world to sit down with Charles Edward and ask him a few important questions. But mortality had its say, and were left with no more than his words on the pages that follow. He probably did not expect his diary to be read so far into the future. Diary words are usually not intended for others to read. And I think this diary is no exception. There is little self-serving to impress others. Instead, what I think the diary entries represent is an accounting to his better self.

As a young man coming of age, Charles Edward prides himself on discipline and good habits. He forgoes taking a streetcar and walks fifty blocks because he is practicing economy, as if hes acting on one of Benjamin Franklins self-improvement maxims. And because this must be an accounting to himself, I think we read the words for the appealing honesty.

Before getting to the diary entries, Id like to mention I dont want to burden the reader with Dickinson genealogy. Moreover, any Dickinsonia I might elaborate would have an intrinsic bias. For if I say I am a direct descendant of Nathaniel Dickinson (1601-1670), an English Puritan who reached British America in 1636, who co-founded Hadley, Massachusetts, and whose descendants include a literary luminary, Emily Dickinson, I am casting a patriarchal narrative about my connection to this diary of Charles Edward.

I think it equally defensible to counter, on my mothers side, I am a direct descendant of Martin Casillas (1556-1618), a Spanish architect who was commissioned to design the Cathedral of Guadalajara and who was in the New World before Nathaniel.

So I am not suggesting patriarchal lineage matters more than matriarchal lineage. Naming conventions make patriarchy easier to follow across time. With that in mind, my discussion of Dickinson genealogy is mostly to explain some persons mentioned in the diary. Some were interesting to follow up with historical documents. As one example, Charles Edward mentions twice his uncle and aunts daughter, Lily. She is a six-year-old in 1868, and Lily (Evelina) would go onto to graduate from Smith College with a degree in Classical Studies. Later, in her early thirties, Evelina Dickinson would be a Latin instructor and graduate student at Stanford University in Palo Alto when it first opened its doors in 1891.

The presentation of Charles Edwards diary begins with Chapter 1, which is a transcription of his pencilled entries for January 1 through January 15, 1868. Next, in Chapter 2, I summarize, including themes shown by the entries, background information for context, and discussion of some of the more puzzling entries. Presentation of the balance of the diary through May follows this format. The final Chapters 22-23 survey the balance of Charles Edwards life once he left St. Louis for Dubuque. As a help in reading diary entries, Ive included a Cast of Characters in the Appendix. Names mentioned more than once are listed in descending order of mentions. A few details for each suggest the relationship and possible influence on Charles Edward while he wrote the diary.

The St. Louis of 1868, where Charles Edward lives, is busy and thriving as the fourth-largest city in the Union. Amid the disciplined, bourgeois, church-going life of the diarist, memories of the most divisive social upheaval in American historythe Civil War or the War of the Southern Rebellionlinger on a few diary pages. Memories that surely set the stage for Charles Edward noting on May 16, 1868, President Andrew Johnson has avoided removal from office.

Automobiles are unknown in 1868. Charles Edward walks everywhere, and he has a keen sense of weather and its effects, whether ice in the Mississippi River, or violent windstorms unroofing buildings.

Next page