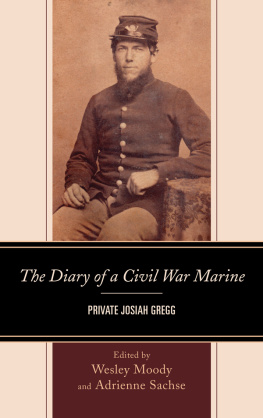

The Diary of a Civil War Marine

The Diary of a Civil War Marine

Private Josiah Gregg

Edited by Wesley Moody and Adrienne Sachse

FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Madison Teaneck

Published by Fairleigh Dickinson University Press

Co-published with The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

10 Thornbury Road, Plymouth PL6 7PP, United Kingdom

Copyright 2013 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.,

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gregg, Josiah, d. 1929.

The diary of a Civil War Marine, Private Josiah Gregg / edited by Wesley Moody and Adrienne Sachse.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-61147-578-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-61147-579-1 (electronic)

1. Gregg, Josiah, d. 1929Diaries. 2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865Naval operations. 3. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865Personal narratives. 4. United States. Marine CorpsHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865. 5. United States. Marine CorpsBiography. 6. Vanderbilt (Side-wheel steamer) I. Moody, Wesley. II. Sachse, Adrienne, 1953- III. Title.

E601.G84 2012

973.7'5dc23

2012026722

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Preface

B etween 1862 and 1865 Josiah Gregg was a US Marine. He served aboard the USS Vanderbilt , where he took part in the search for Conf-ederate raiders in the Caribbean and the Atlantic, and aboard the USS Brooklyn , where he saw action at the Battle of Mobile Bay and Fort Fischer. After the war, Gregg, like most veterans, returned to obscurity. During his service Gregg kept a daily journal. This is a rarity among Civil War sailors and marines.

Like most veterans, Gregg must have found the war to be the most exciting period of his life. As an old man living with his daughter in Minnesota, he must have enthralled his young grandson with tales of exotic locations and the Civil War. His grandson went on to graduate from the US Naval Academy and had two sons who were also academy graduates. It was this grandson, Frederick C. Sachse, who inherited the journal and passed it to his son.

Adrienne Sachse, the wife of Greggs great-great grandson, Stephen Sachse, decided to transcribe the old handwritten journal as a gift to her son and husband, who bucked family tradition by becoming a US Army officer. Adrianne is a professor of economics at Florida State College at Jacksonville. It was there that she shared the journal with me, a Civil War historian, who convinced her that this family treasure should be shared with scholars and students of the Civil War.

Wesley Moody

Editors Note

F or the most part this journal is presented as Gregg wrote it. For the sake of modern readers, I have taken the liberty of making a few changes. I hope these changes will make the journal more readable without affecting the spirit of his words. Misspellings are corrected only when the misspelling is not significant. For example throughout the journal Gregg refers to the berth deck as the birth deck. This simple misspelling could be changed without any real effect. Gregg also had the annoying habit of using ampersands. This is understandable considering he was writing by hand and his available space was limited, but and can be substituted for the sake of the modern reader.

I am very aware that the audience is Greggs audience. I have tried to use footnotes only sparingly when I feel Gregg needs to be clarified or when it will add significantly to his narrative. I am greatly honored but also humbled to have had the opportunity to help bring Greggs words to historians and the public.

Introduction

J osiah Collins Gregg was born on October 24, 1840, in Newburgh, New York. He lived in Bath, New York, at the time of his enlistment. He was a schoolteacher before joining the United States Marine Corps (USMC) on August 23, 1862, in Brooklyn, New York. He listed his occupation as clerk, but since he enlisted in the summertime, he obviously had to find other employment until the school year began again. He was described on his enlistment papers as 5' 6 " tall with blue eyes, brown hair, fair complexion and free from bodily defects. Unfortunately, the twenty-one-year-old Gregg does not tell us why he made the decision to join the marines.

Gregg joined the marines just after President Lincoln signed the Militia Act and the State of New York began organizing the system of militia draft by county. The navy and marine corps enjoyed a serious boost in the number of enlistments at that time. Enlistments in the navy and marines did not count toward a states numbers but a man in one of the services would be safe from the draft. Friends and family members often looked down on men who became sailors instead of joining the army. Many men joined the navy thinking they would be safer and have easier duty than soldiers. The idea of prize money, a sailors share of the worth of a captured blockade runner, was used as a recruiting tool by the US Navy. There is very little literature about the marine corps during the Civil War. Nothing has been written about the marines like James McPhersons For Cause and Comrades, Why Men Fought in the Civil War or Michael Bennetts Union Jacks, Yankee Sailors in the Civil War .

One can assume that many of the things that attracted men to the navy attracted men to the marines with the added bonus of being exempt from much of the backbreaking labor required of sailors. The lure of seeing exotic places, prize money and avoiding the major land battles must have been powerful. Of course, there were some major flaws in this line of thinking. Most Union sailors saw nothing more exotic than the Atlantic and Gulf Coast of the American South. There was very little prize money and that which was paid out was often years after the end of the war. Most importantly, many sailors learned that naval combat could be as dangerous and bloody as land battles.

The idea of joining the marines in order to avoid the dangers of combat is foreign to our modern way of thinking. The US Marines are very proud of their tradition of being the first to fight, but this is a reputation earned after the American Civil War. There were 1,775 men and officers in the USMC in 1860. Their duties were mainly security aboard ship and for naval facilities. More than once during the Civil War, marines are called on to repress a mutinous crew. The old mission of the marines as sharpshooters in the rigging was fading with the advent of new long-range naval artillery. As the navy grudgingly changed from sail to steam, the necessity of the marines was called into question. Critics argued that the navy could create its own security force. There was even serious discussion during the Civil War of transferring the marine corps to the army. It would not be until the 20th century that the corps developed its own unique mission. In the Civil War, however, the marine corps had to justify its existence, and Civil War marines were assigned as one of the gun crews, a mission that won many marines the Congressional Medal of Honor during the war but would not be enough of a justification to exist as a unique service.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.