Editor: Liz Aneloski

Technical Editor: Diana Roberts

Copy Editor: Judith Moretz

Cover Designers: Kathy Lee and John Cram

Design Director: Diane Pedersen

Book Designer: Ewa Gavrielov

Illustrator: Kandy Petersen

Photographer: Jon Blumb, unless otherwise noted

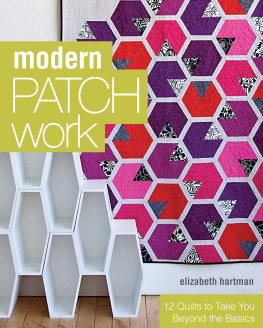

INTRODUCTION

Last year I was in Charleston, South Carolina, thinking about writing this book when someone apologized to me for the attitude I might encounter as a Yankee in the old Southern city. Please understand, she laughed, the Woah is not over down here. I could only tell her that the Woah was not over in my hometown either. In Lawrence, Kansas, we had just decided, after much community discussion and dissension, to name our new school Free State High School. Students would be ever reminded of our origins back in the years of Bleeding Kansas, when free-state Jayhawkers battled slave-state Bushwhackers over the question of slavery.

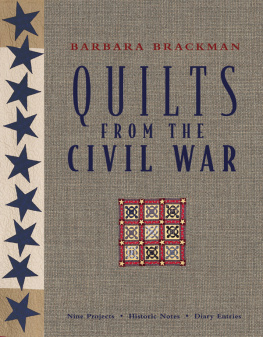

This book on Americas Civil War and its quilts, then, is by a Northerner, proud to live in a town with a Free State High School. I realize where my prejudices lie, yet I have tried to listen carefully to the voices of the Southern women and give them and their quilts equal weight in telling the story of the War.

I have also tried to bring these women alive with words from their diaries, letters, and memoirs, with photographs of them and their children, and especially with their quilts. In their written words I have left grammar and spelling errors as they appeared in print, but with spoken words transcribed by someone else into dialect I have paraphrased the dialect into regular English. The dialect serves to distance us too much from the speaker.

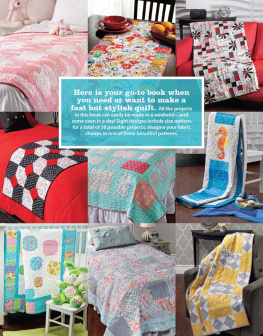

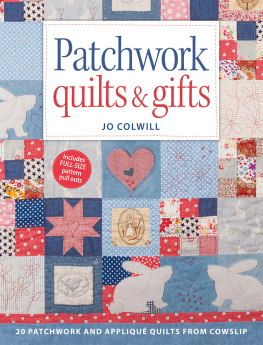

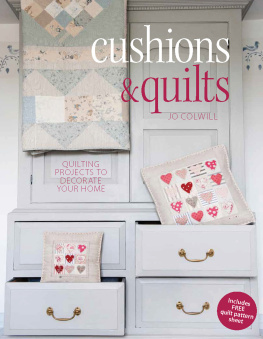

The book encourages the reader to make a connection to the women of the Civil War era by copying their quilts. Some quilters make a faithful copy of the original, matching each block to reproduction fabrics. These faithful copies are wonderful exercises in quilt history, teaching the copyist much about fabric and design attitudes of the era. Many quilters make an adaptation, beginning with the basic idea, but adding and changing borders, updating color schemes, and introducing a modern aesthetic. And some use a quilt or an incident as a point of inspiration, creating an interpretationa quilt that might have existed.

Use the many letters and diaries of Civil War era women that are being published and republished today for inspiration. In their words youll find lives that were funny, sweet and sad, and sometimes, like that described in Mary Lincolns letters, absolutely horrific. Youll find those women staring soberly at us in the carte-de-visite and tintype photographs to be just like us and yet not the least like us. Youll make new friends with women who lived long ago. Nothing can give you better insight into the era.

And while we are on the subject of new friends and old, I want to thank those who made the quilts pictured in the book. I owe much to Terry Clothier Thompson, whose fanciful interpretations inspire so many others. Terry wrote much of the pattern directions here. And thanks to Cherie Ralston, who checked our patterns and made a wonderful Union quilt. I also want to thank quiltmakers Gail Bakkom, Bobbi Finley, Linda Frost, Nancy Hornback, Mary Madden, Patti Mersmann, Ruth Powers, Sherri Rush, Wava Stoker-Musgrave, Shirley Wedd, Shirlene Wedd, and Jeananne Wright.

Calico Flag by Linda Frost.

A copy of a flag made by Palmyra Mitchell, Union Mills, Missouri, 1863. For her story, see .

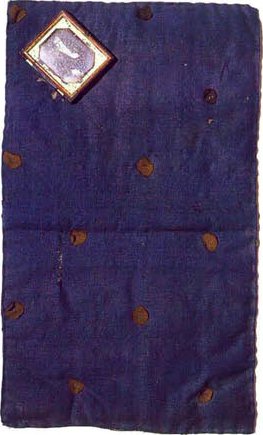

Collection of period pieced items with a reproduction housewife or sewing kit.

CHAPTER 1

Petticoat Plotters Quilts for Freedoms Fair

To the chivalrous sons of the South:

Most chivalrous gentlemenpardon us; pray

And pity our present condition.

The lady fanatics have carried the day,

And openly preach Abolition!

The petticoat plotters, with might and with main,

Are tearing the bonds of the Union atwain.

Ladies Anti-Slavery Society of [Concord] New Hampshire,

Liberator, January 3, 1835

Unknown woman with needlework.

More ink and paper has been devoted to the American Civil War than to any other topic in the English language. Yet the shelves and shelves of books rarely discuss the War from the perspective of half of those who lived through itthe women. And too often when women are discussed they are portrayed as sitting mute, impotently waiting at home. In truth, women played many active roles in the Civil War, roles that are hardly remembered. Among their most vigorous activities was chafing the nations conscience in the thirty years leading up to the conflict.

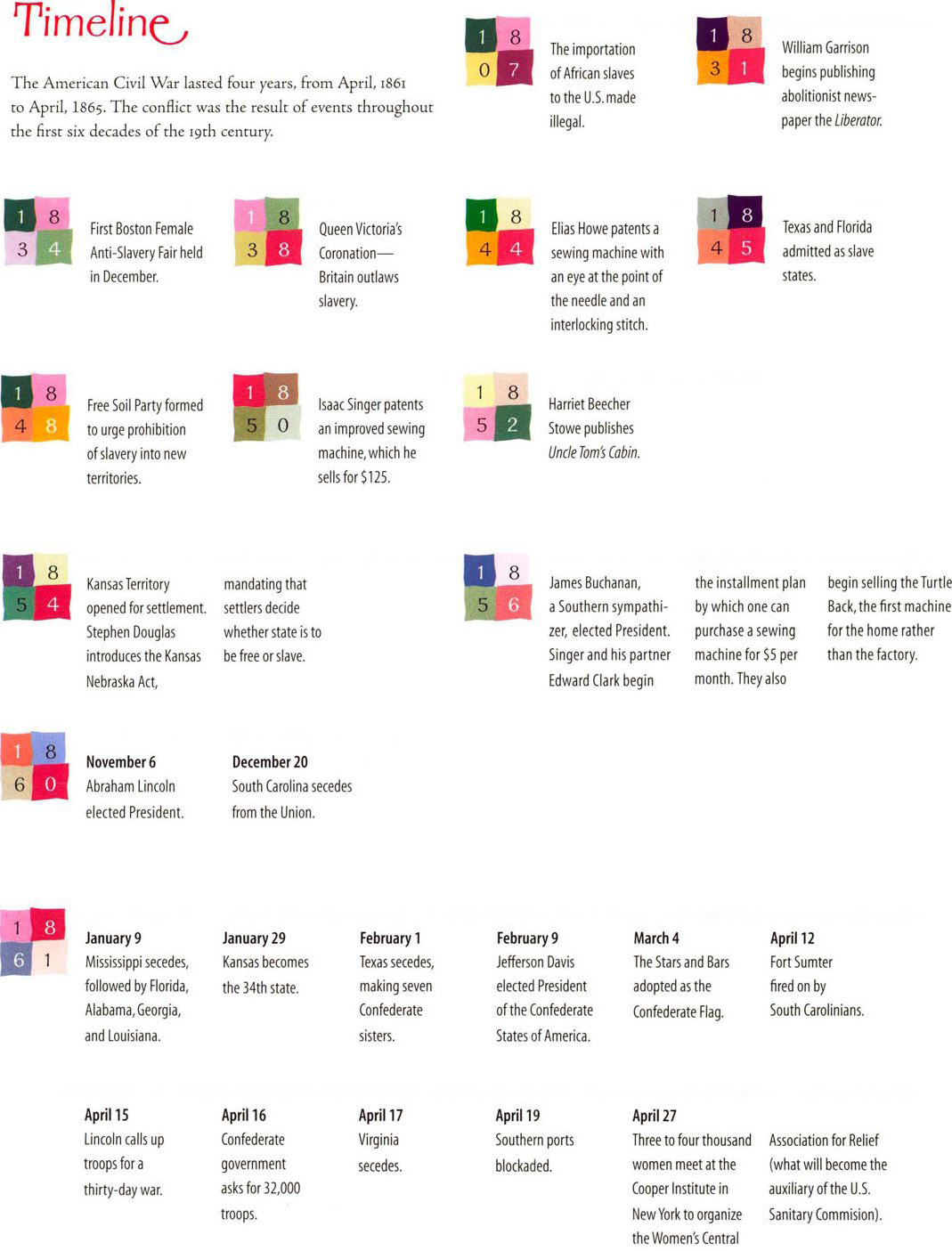

Abolition, the elimination of slavery, began as a radical idea held by a few religious and political Americans. Through the first half of the nineteenth century abolition grew into a national concept that resulted in Emancipation, and later the Thirteenth amendment to the Constitution, which freed the slaves, in 1865. Many white Americans initially resisted the idea of absolute freedom for all African-Americans, but they also realized the hypocrisy of a system of slavery thriving in a nation rooted in liberty.

Abolitionists forced this disparity into the center of a national debate about American identity. Using tactics familiar today they relied on the written word to raise consciousness about the evils of slavery. Abolitionists presented their arguments in newspapers, petitions, fiction, political pamphlets and tracts, broadsides (handbills), and even in needlework. When pincushions are periodicals and needlebooks are tracts, discussion can hardly be stifled or slavery perpetuated.

At the heart of their message was a conviction that slaves were people with human needs and human rights, a radical idea because, in the words of Angelina Grimk Weld, One who is a slaveholder at heart never recognizes a human being in a slave.

Abolition:

The idea of eliminating slavery.

Emancipation:

The Presidential decree that liberated slaves in Confederate territory in 1863.

Thirteenth Amendment:

The amendment to the U.S. Constitution, passed in 1865, stating that slavery shall not exist within the United States.

Fragment of a tied comforter made in Boston about 1855, with a photograph of Dr. Sylvester B. Prentiss. Collection of the Kansas State Historical Society. Photo courtesy of the Kansas Quilt Project.

Next page