2017 University of South Carolina

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.sc.edu/uscpress

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/

ISBN: 978-1-61117-764-0 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-1-61117-765-7 (ebook)

Front cover photograph: Ulf Anderson

www.ulfanderson.photoshelter.com

SERIES EDITORS PREFACE

The Understanding Contemporary American Literature series was founded by the estimable Matthew J. Bruccoli (19312008), who envisioned these volumes as guides or companions for students as well as good nonacademic readers, a legacy that will continue as new volumes are developed to fill in gaps among the nearly one hundred series volumes published to date and to embrace a host of new writers only now making their marks on our literature.

As Professor Bruccoli explained in his preface to the volumes he edited, because much influential contemporary literature makes special demands, the word understanding in the titles was chosen deliberately. Many willing readers lack an adequate understanding of how contemporary literature works; that is, of what the author is attempting to express and the means by which it is conveyed. Aimed at fostering this understanding of good literature and good writers, the criticism and analysis in the series provide instruction in how to read certain contemporary writersexplicating their material, language, structures, themes, and perspectivesand facilitate a more profitable experience of the works under discussion.

In the twenty-first century Professor Bruccolis prescience gives us an avenue to publish expert critiques of significant contemporary American writing. The series continues to map the literary landscape and to provide both instruction and enjoyment. Future volumes will seek to introduce new voices alongside canonized favorites, to chronicle the changing literature of our times, and to remain, as Professor Bruccoli conceived, contemporary in the best sense of the word.

Linda Wagner-Martin, Series Editor

CHAPTER 1

Understanding Gary Shteyngart

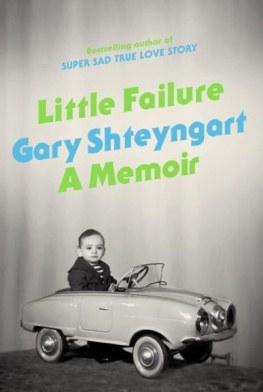

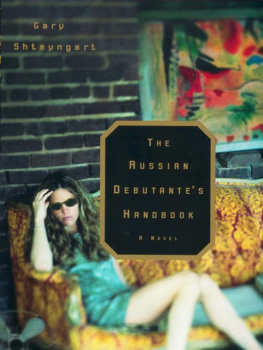

Few contemporary authors have met with the combination of critical and commercial success enjoyed by Gary Shteyngart. He arrived as a literary star in 2002 with The Russian Debutantes Handbooka novel largely responsible for propelling an enduring surge of Russian American writingand confirmed his place on the American literary scene with two more novels, Absurdistan (2006) and Super Sad True Love Story (2010), and a memoir, Little Failure (2014), each of which has garnered prestigious prizes and become a national bestseller. Shteyngarts oeuvre also includes acclaimed travel writing for the New York Times, the New Yorker, and Travel + Leisure; YouTube videos featuring Hollywood stars such as James Franco and Paul Giamatti; and a stunning number of blurbs for others works (endorsements that are themselves the source of a cult following on Tumblr and a documentary by the author and television writer Jonathan Ames). No longer just a literary name, Shteyngart is by now well established as a literary personality, and he engages much of his current readership (and future readers) online, as a celebrity known for his comic persona: a not-quite-assimilated Russian Jewish immigrant, amusingly dishevelled and blundering, part Slavic clown, part schlemiel.

One obvious attraction of Shteyngart as an author is his brilliance as a comic writer. Michiko Kakutani, reviewing Little Failure in the New York Times, has put it well: Of the many enormously gifted authors now writing about the immigrant experienceincluding Jhumpa Lahiri, Edwidge Danticat, Dinaw Mengestu, Chang-rae Lee, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Gish JenGary Shteyngart is undoubtedly the funniest (with Junot Daz a close runner-up).but all his work is distinguished by a delightful exuberance and ingenuity, a playfulness that often moves arrestingly into the grotesque.

Shteyngart is also an exceptionally astute observer and satirist of contemporary life. He has deftly explored the intricacies of identity politics in the twenty-first century, and his manipulation of multiple literary traditions has revised seminal mythologies of racial and ethnic belonging in cannily playful ways. Often characterized as a Russian American author (and, less commonly, a Jewish American one), he has particularly illuminated the exilic conditions of Russian Jewish identities in the United States, as well as across the global diaspora of Russians and Jews. With the publication of Super Sad True Love Story, which presents a near-future American dystopia, Shteyngart has broadened his thematic foci by engaging some of the most profound and rapidly developing social transformations of the modern era. The novelhis most ambitious and significant work thus farprovides insights into the (sur) reality of hyper-technologized, globally-networked life, and vivid depictions of the impact of social networking culture on privacy, civility, literacy, sexual expression, and material consumption. Though he has sometimes been dismissed as simply an immigrant author performing a rather marginal ethnic shtick, Shteyngarts work deserves analysis for its remarkable centrality: its relevance to core questions of identity-formation and belonging, and of tradition and the conditions of belief, common to globalized societies.

Shteyngart, an only child, was born Igor Semyonovich Shteyngart in 1972, in what was then Leningrad in the Soviet Union. His parents were relatively prosperous: his mother taught piano at a kindergarten, and his father pursued a generally uninspiring career engineering large telescopes at the famous LOMO photography factory.

Shteyngarts keen sense of being an outsider, and of having to work hard to understand, and somehow meet, the expectations of his social milieu, began with this difficult assumption of a Russian Jewish American identity.

So strong was cold-war hysteria in Reagans America, Shteyngart has recalled, that it made sense to him to assumeor attempt to assumean ostensibly less threatening ethnicity among his young peers:

one day after one Commie comment too many, I tell my fellow pupils that I wasnt born in Russia at all. Yes, I just remembered it! It had all been a big misunderstanding! I was actually born in Berlin, right next to Flughafen Berlin-Schnefeld, surely youve heard of it.

So here I am trying to convince Jewish children in Hebrew school that I am actually a German.

And cant these little bastards see that I love America more than anyone loves America? I am a ten-year-old Republican. I believe that taxes should only be levied on the poor, and the rest of Americans should be left alone. But how do I bridge that gap between being Russian and being loved?