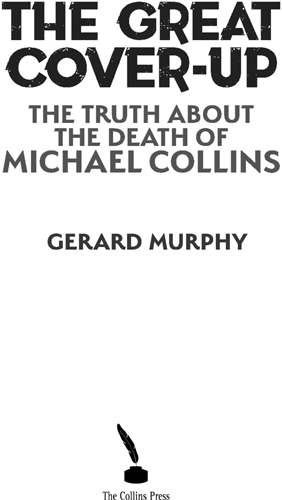

GERARD MURPHY, from Cork, is the author of the ground-breaking The Year of Disappearances: Political Killings in Cork 192122 (2010), as well as two critically acclaimed novels. He holds a PhD from University College Cork and lectures at the Institute of Technology, Carlow.

Map of County Cork (Mike Murphy, Department of Geography, University College Cork)

Map of the ambush site at Bealnablath, County Cork. Known IRA positions indicated by X. (Mike Murphy, Department of Geography, University College Cork)

There is no use in going to work like a horse or an ass or a beast of burden. Put your heart and soul into everything you do. That is the only way to succeed.

Michael Collins

(Sunday Independent, 27 August 1922)

A man of immense ability and untiring energy, and thoughtfulness for others. At the end of the day, when most people would look for a rest, I have known him to go around looking for relatives of people who had suffered a loss, to try and give them some comfort. And this was from a man who never had a free moment for himself. He was a patriot, a most courageous man, and a great, great gentleman.

Emmet Dalton

(P.J. Twohig, The Dark Secret of Bealnablath, Cork, 1991)

It has come to a very bad pass when Irishmen congratulate themselves on the shooting of a man like Michael Collins.

amon de Valera, upon hearing of Collinss death

(E. Neeson, The Life and Death of Michael Collins, Cork, 1968)

Such a claim is a claim to military despotism and subversive of all civil liberty. It is an immoral usurpation and confiscation of the peoples rights.

(George Count Plunkett referring to the proposed trying of

Michael Collins for treason, in Manifesto to the Irish People,

De Valera Papers, UCD P150/1630)

L ast year I was fortunate enough to attend a public talk given by the well-known physicist Professor Brian Cox. He made a comment which, though it was about science, is relevant in a historical context. Scientists, he said, rarely if ever set out to answer Big Questions. Rather they set out to answer small questions. And if these offer clues to the Big Questions, then that is how the process of inquiry works. Science has many examples of this, but history has them too or should have. I did not set out to write a book on Michael Collins, much less on his death. I had little interest in Collinss death, believing like most historians that the matter was long settled. However, even if it was settled, it must still rank among the big events in Irish history. For Collinss death surely changed Irish history in ways that, by definition, can never be established. So if there was a question about it, then by definition again it was a Big Question.

I stumbled into Bealnablath, much as Collins did, by accident. I was studying the papers of Florence ODonoghue, former Adjutant of the 1st Cork Brigade of the IRA and later of the 1st Southern Division, and the IRAs chief intelligence officer in Cork during the War of Independence and later one of the first historians of the Irish revolution. One of the striking things about ODonoghues papers is how often they contain material that is at odds with reality, when the motivation for their writing was clearly propagandist. ODonoghue often felt the need sometimes to an alarming degree to defend his own particular version of events and to mould the historical record in ways that suited his own ends. In this, he was largely successful. The historical establishment, for the most part, have accepted his accounts to the extent that it is almost a historiographical mortal sin to try and contradict them. Only recently have serious questions been asked of this.

This is not the place to deal with these broader issues. Suffice it to say that one of the subjects that seemed to exercise ODonoghues pen to an unexpected degree, though he never wrote about it in book form, was the death of Michael Collins. As a supposed Neutral during the Civil War, one would expect he would have no direct part in, or first-hand knowledge of, the topic. Yet time and time again when articles appeared in newspapers or when biographies of Collins were published, ODonoghue was sending off missives to newspapers or having articles published, usually in the Sunday Press, promoting his view on the subject: that Collins was killed and could only have been killed as a result of an accidental shot fired during a haphazard, hastily convened ambush.

And so, from trying to answer one of the small questions why was ODonoghue so interested in Bealnablath? I stumbled on one of the Big Questions: why did Michael Collins die the way he did, in that particular set of circumstances at that particular time? This will almost certainly not be the last word on the death of Collins. Nor does it answer some of the most basic questions, such as who was the man who shot Michael Collins. But I believe it does ask many of the right questions. Collinss death is not a done deal. Far from it. A lot of unresolved issues remain. But the book establishes, in my view, that the accepted model on the death of Collins, though perfectly plausible, is very likely to be wrong. My conclusion is that Collins was assassinated rather than was the victim of a virtual accident. That the whole thing is shrouded in mystery and that almost everybody concerned tried to lie about it for perfectly understandable reasons in many cases is incontrovertible.

So how does one thread through the minefield of lies and half-truths that surround Bealnablath? By giving primacy to documentation produced during the week of the ambush itself and shortly afterwards. What emerges from this is a picture quite at odds with the accepted version of events. This is what happens to Big Questions when you start digging to find answers to smaller questions: you find yourself in quite unexpected places.

I n a review on the publication of Tim Pat Coogans biography of Michael Collins, historian and broadcaster John Bowman stated that Michael Collins is sexy: probably in both senses of the word, but certainly in the sense in which it has lately gained currency. Bowman seemed to imply that there had been far too many books written about Collins, many of them poor, most of them falling somewhere between hagiography and conspiracy theory. Collinss fascination to so many writers is a liability, Bowman wrote. Too often it is the legend of Collins which attracts: the swashbuckling man of violence, the man who turned the heads of Londons society hostesses; above all, the lost leader, cut down in his prime.

But if Collins is sexy, that is no reason to write another book about him. Perhaps there should be a moratorium on further books on Collins, at least unless significant new information is released from state and private archives which is probably unlikely at this stage. So what do you do if you come across what you believe is new evidence on Collinss death or at least evidence that has been overlooked for almost a hundred years? Do you ignore it, on the basis that enough has been said already? After all, do you want to be like the conspiracy theorist who goes to heaven only to be told that JFK was simply shot by Lee Harvey Oswald, a lone gunman? Or do you say your piece, on the basis that if you dont, somebody else probably will? At the risk of adding to the conspiracy theories surrounding the death of Collins, I decided, when I came across what I believed to be such evidence, to take the latter course.