INTRODUCTION

Table of Contents

WILLIAM HAZLITT

Table of Contents

I

Table of Contents

Hazlitt characterized the age he lived in as critical, didactic, paradoxical, romantic. gave to his writings the very qualities which he enumerated as characteristic of the age, and his consistent sincerity made his voice distinct above many others of his generation.

Hazlitts earlier years reveal a restless conflict of the sensitive and the intellectual. His father, a friend of Priestleys, was a Unitarian preacher, who, in his vain search for liberty of conscience, had spent three years in America with his family. Under him the boy was accustomed to the reading of sermons and political tracts, and on this dry nourishment he seemed to thrive till he was sent to the Hackney Theological College to begin his preparation for the ministry. His dissatisfaction there was not such as could be put into wordsperhaps a hunger for keener sensations and an appetite for freer inquiry than was open to a theological student even of a dissenting church. After a year at Hackney he withdrew to his fathers home, where he found nothing more definite to do than to solve some knotty point, or dip in some abstruse author, or look at the sky, or wander by the pebbled sea-side. How acutely sensitive he was to all impressions at this time is indicated by the effect upon him of the meeting with Coleridge and Wordsworth of which he has left a record in one of his most eloquent essays, My First Acquaintance with Poets. But his active energies were concentrated on the solution of a metaphysical problem which was destined to possess his brain for many years: in his youthful enthusiasm he was grappling with a theory concerning the natural disinterestedness of the human mind, apparently adhering to the bias which he had received from his early training.

But being come of age and finding it necessary to turn his mind to something more marketable than abstract speculation, he determined, though apparently without any natural inclination toward the art, to become a painter. He apprenticed himself to his brother John Hazlitt, who had gained some reputation in London for his miniatures. During the peace of Amiens in 1802, he travelled to the Louvre to study and copy the masterpieces which Napoleon had brought over from Italy as trophies of war. Here, as he marched delighted through a quarter of a mile of the proudest efforts of the mind of man, a whole creation of genius, a universe of art,

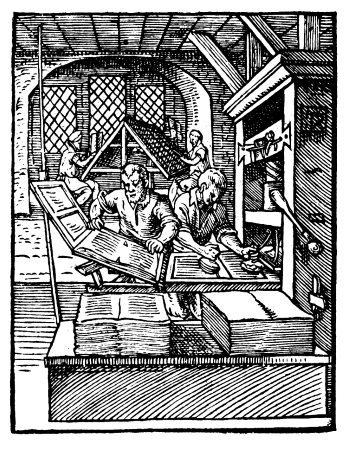

When Hazlitt abandoned painting, he fell back upon his analytic gift as a means of earning a living. Not counting his first published work, the Essay on the Principles of Human Action, which was purely a labor of love and fell still-born from the press, the tasks to which he now devoted his time were chiefly of the kind ordinarily rated as job work. He prepared an abridgement of Abraham Tuckers Light of Nature, compiled the Eloquence of the British Senate, wrote a reply to Malthuss Essay on Population, and even composed an elementary English Grammar. It would be a mistake to suppose that these labors were performed according to a system of mechanical routine. Hazlitt impressed something of his personality on whatever he touched. His violent attack on the inhuman tendencies of Malthuss doctrines is pervaded by a glow of humanitarian indignation. For the Eloquence of the British Senate he wrote a sketch of Burke, which for fervor of appreciation and judicious analysis ranks with his best things of this class. Even the Grammar bears evidence of his enthusiasm for an idea. Whenever he has occasion to express his feelings on a subject of popular interest, his manner begins to grow animated and his language to gain in force and suppleness.

But Hazlitt continued firmly in the faith that it was his destiny to be a metaphysician. In 1812 he undertook to deliver a course of lectures on philosophy at the Russell Institution with the ambitious purpose of founding a system Though he did not succeed in founding a system, he probably interested his audience by a stimulating review of the main tendencies of English thought from Bacon and Hobbes to Priestley and Godwin.