WILL

DOLLARS

SAVE

THE WORLD?

BY HENRY HAZLITT

D. APPLETON-CENTURY COMPANY, INC.

New YorkLondon

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THE AUTHOR wishes to thank Newsweek and Plain Talk for permission to reprint here some passages from his own writing that originally appeared in their pages. He is also indebted to the National City Bank of New York and Prentice-Hall, Inc. for statistical tables which appear here as appendices. Those who have helped him with their suggestions and comments are unfortunately too numerous to mention.

Copyright 1947, by Henry Hazlitt

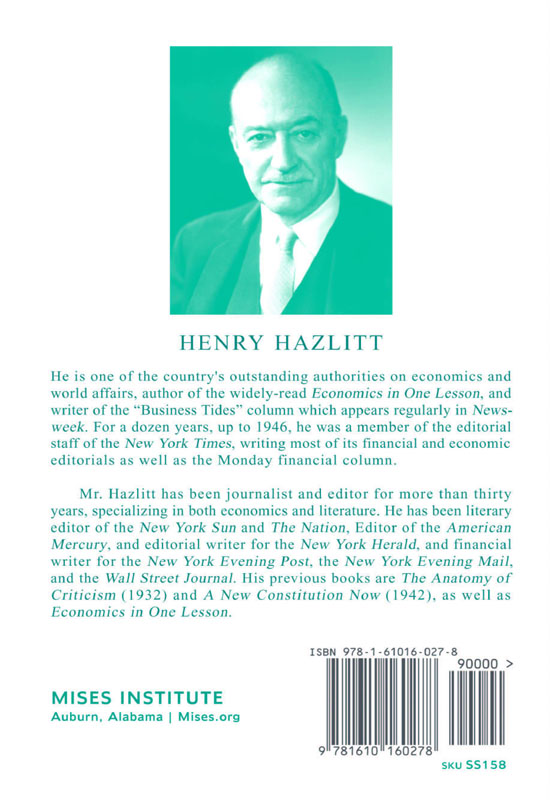

The Author

LIKE the famous British economist Walter Bagehot, whom he admires, Henry Hazlitt has been a writer in diverse fieldsliterary criticism, philosophy, politics, economics and finance. He was literary editor of The New York Sun from 1925 to 1929, literary editor of The Nation from 1930 to 1933, and succeeded H. L. Mencken as editor of The American Mercury in 1933. One result of his ten years of book-reviewing was The Anatomy of Criticism, published in 1933. His deep interest in political questions led to the book, A New Constitution Now, published in 1942.

But except for the interruption of the years devoted to literary criticism, Henry Hazlitts dominant interest, since he first became a reporter on The Wall Street Journal more than thirty years ago, has been in economics and finance. In 1916 he became a member of the financial staff of the New York Evening Post. During our participation in the first World War he was in the air service. On his return to civilian life he wrote the financial letter of the Mechanics & Metals National Bank, then one of the ten largest banks of the country but since absorbed by The Chase National Bank. He was only 26 when he became financial editor of the New York Evening Mail. After the disappearance of the Mail through its purchase by Frank A. Munsey he became a member of the editorial staff of Munseys New York Herald, a position which he held until that newspaper in turn was acquired by and merged with The New York Tribune.

In 1934 Mr. Hazlitt became a member of the editorial staff of The New York Times, and in that capacity he wrote most of its financial and economic editorials. He also later wrote the Monday financial column. He remained on the staff of The Times for twelve years, and in September 1946, he became the writer of the Business Tides column for Newsweek. In 1946 he published Economics In One Lesson, one of the few serious economic works to become a best seller in recent years. The book has been published also in England, and French and Spanish translations will soon appear.

Mr. Hazlitt has addressed many business and university audiences. Early this year he spent a month in Mexico as a visiting lecturer at the Instituto Technologico, and studied economic conditions in that country. This spring he spent two months in Europe, visiting half a dozen countriesSwitzerland, France, Belgium, Holland, Sweden and Great Britainand writing a series of articles on European conditions which appeared in Newsweek.

CONTENTS

WILL DOLLARS SAVE THE WORLD?

THERE is a widespread belief that the United States has a duty to lend or give huge sums to other countries, principally in Europe, if it is to save the world from communism and chaos. This belief is held almost as strongly in the United States, which would make the sacrifices, as it is in the European countries that are expected to benefit from them.

In its most widely held form the conclusion rests on the assumption that the present economic difficulties of Europe are in the main the consequences of the destruction and dislocations of war. It is assumed that there is a definite deficit that America can make up by loans or gifts, that America must supply this if Europe is to recover, that Europes economic recovery is essential for Americas prosperity, and that therefore it is good business for America to make these gifts or loans, even if the loans are never repaid. The sacrifices in the present, it is argued, will be more than compensated by gains in the future.

This set of assumptions found expression in the celebrated speech of General George C. Marshall, the American Secretary of State, at Harvard on June 5th:

The truth of the matter is that Europes requirements, for the next three or four years, of foreign food and other essential productsprincipally from Americaare so much greater than her present ability to pay that she must have substantial additional help, or face economic, social and political deterioration of a very grave character.

The implication of this statement is that Europes shortages are being imposed upon her by conditions beyond her control, and that the present import surplus of Europe is solely the result of these shortages and not of other factors. This is also the contention that runs throughout the report of sixteen European nations on the Marshall plan.

It would be ungenerous and short-sighted to minimize the appalling physical destruction and the enormous economic and political problems that the last World War brought upon Europe. We can never forget that in the war against Nazism England stood for a whole year alone. Thousands of her houses and factories were destroyed by blitz. Her peacetime equipment ran down. Her export trade was reduced to less than a third. Most of her foreign investments had to be sold.

Yet when all this has been admitted, we must go on to ask ourselves in all candor whether it is the destruction and dislocations of the war or the governmental policies followed since that war which are primarily responsible for the present European crisis. And whatever we decide regarding the causes of the present crisis, we must also keep in mind that the central question we have now to answer is not what caused it, but what measures and policies are most likely to cure it. Our real problem is not the past, but the future.

Let us begin, therefore, by taking a closer look at the existing situation in Europe.

CHAPTER II

PROBLEM No. 1: GERMANY

IN ANY economic survey of Europe, however brief, it is most profitable to begin with Germany. Germany has become the economic cancer spot of Europe. It has been producing a pitiable fraction of its pre-war industrial output. Steel production in the British and American zones, which reached 17,800,000 tons in 1938, has been cut down in 1947 to a bare 2,800,000. To support their own economies, the Allies have tried to encourage at least the production of coal. But the bi-zone in Western Germany, even according to the optimistic estimates of the sixteen European nations reporting on the Marshall plan, will produce only 133,000,000 tons of coal and lignite in 1947 compared with 206,000,000 in 1938. As the Ruhr, second only to Britain, was the greatest pre-war source of Europes coal supply, the result of this output shrinkage has been to slow down the whole economy of Europe.

The industrial paralysis deliberately imposed on Germany by Allied policy has forced Great Britain and the United States to pay the Germans reverse reparations. America has had to pour in foodstuffs to check starvation and disease.

All the countries surrounding GermanySwitzerland, France, Belgium, Holland, Denmark, Swedenwhose economies were closely tied in with hers, have suffered through the German collapse. And not merely because of a coal shortage. Holland, to cite but a single illustration, has suffered both as exporter and importer. Its ports of Rotterdam and Amsterdam, which served not only Holland itself, but the great hinterland of which Germany was the most important part, are largely idle because they no longer serve that hinterland. Dutch vegetable growers find their principal market cut off. On the side of supply, half the machines in Holland are of German make. But spare parts for them cannot under present conditions be obtained from Germany. The result is that when a single part is broken or worn out a whole machine becomes idle. The absence of a machine may in turn slow down a whole factory.