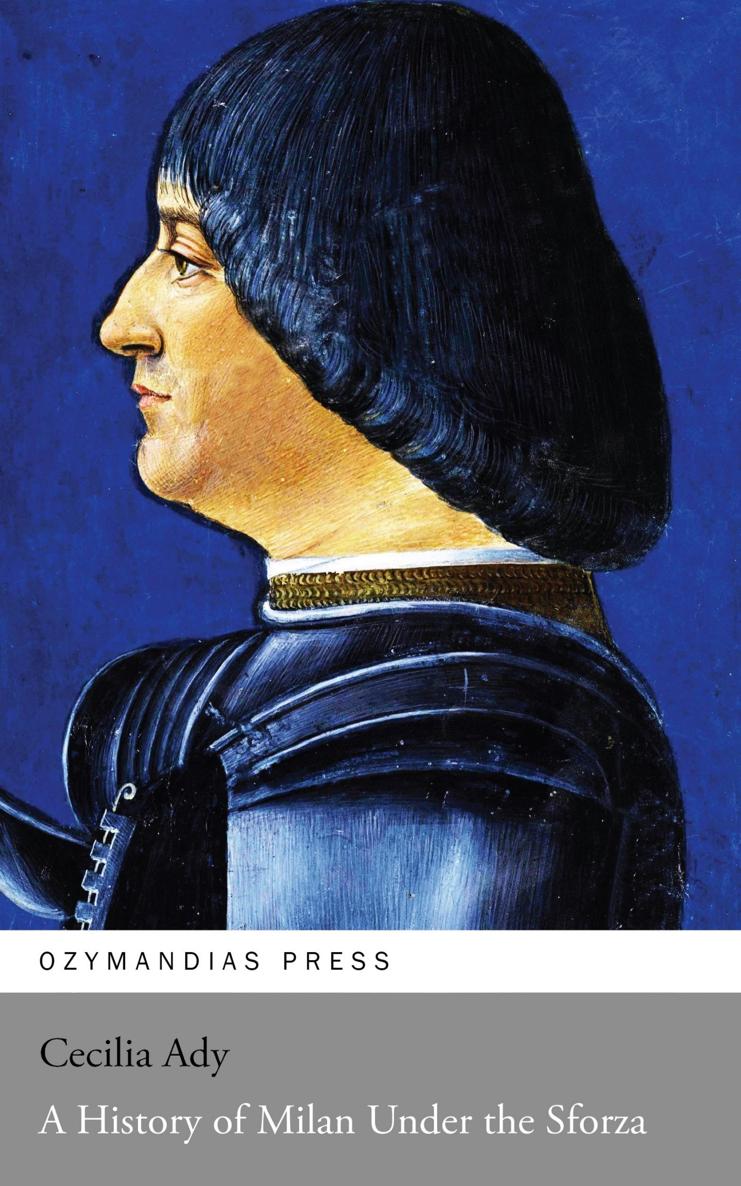

SFORZA AND HIS SON SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE (1369-1433)

IN THE LITTLE ROMAGNOL town of Cotignola, on 28th May, 1369, the founder of the House of Sforza first saw the light. At that time Milan had not yet become a Duchy, although under the joint rule of Bernab and Galeazzo Visconti, it was fast being welded into a State. The Italian soldier of fortune, moreover, was not yet a factor in politics. Only in 1379 did the Company of S. George, consisting purely of Italians, fight and win its first battle against the French mercenaries, who were threatening Rome in the interest of the anti-Pope. Hence the birth of the fifth son of Giovanni Attendolo excited no interest beyond the bounds of Cotignola. None could tell that the boy himself would become the chief of Italian condottieri. Still less could it be imagined that his son would one day mount the throne of Milan. Nevertheless, in the course of the next century both these feats were accomplished, and in Francesco Sforzas recognition as Duke of Milan the Italian soldier of fortune won his crowning triumph. During the years that intervened the peculiar characteristics of the condottiere system were developed, chief of which was the desire of every mercenary captain to make himself an independent prince. Not only did he need a State to support himself and his troops in time of peace, but it was the natural instinct of the hired soldier to aspire to the position of his employer, in order to become, in the words of a Sforza chronicler, hammer and not anvil. Thus the partition of the Duchy of Milan among his generals, on the death of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, and the dominion which Braccio won for himself round Perugia, foreshadowed Francesco Sforzas acquisition of the most powerful State in Italy. From the point of view of the condottiere, it was a triumph. From the point of view of the prince, it formed a striking illustration of Machiavellis assertion as to the danger of trusting to mercenary arms. If your hired captain is skilful, Machiavelli declares, he will always work for his own ends; while, if he is a bad soldier, he will ruin you in the ordinary way.

The rise of the House of Sforza from the camp to the Duchy is a matter of history. Popular tradition adds a still more romantic element to the story by making Muzio Attendolo of peasant birth. One day, runs the legend, when a troop of mercenaries were riding through the flat marshy country between Ravenna and Bologna, they came upon a peasant lad who was cutting wood near his nativ e town of Cotignola. Struck by the boys appearance, they called out to him to join them. He replied by throwing his axe into the branches of an adjacent oak: If it stays, I will go, he cried. The axe stuck in the tree, and Sforza went forth to found a line of Dukes.

As is the fate of all popular stories, the legend of the axe has been declared to have no foundation in history. Yet, unlike the majority of legends, it is known to be practically contemporary. As early as 1411, Pope John XXIII., furious at Sforzas desertion of his service for that of King Ladislas of Naples, caused his enemy to be depicted hanging from his right leg and holding an axe in his hand, while the following lines were attached to the picture:

Io sono Sforza, villano della Cotignola, traditore; Che dodici tradimenti ho fatto alla Chiesa contro lo mio onore. Promissioni, capitoli, patti haio, rotti.

Freely circulated in the camp of Sforzas rival, Braccio, the story is told by three chroniclers of a slightly later date. It was also known to the later members of the House of Sforza. When Francesco Sforza II. was exhibiting the marvels of the Castello of Milan to Paolo Giovio, the Duke remarked with a smile, We owe it all to that famous axe, which our ancestor threw into the branches of a tree, and which, to our good fortune, stayed there. There is, moreover, no inherent improbability in the legend, as many of the most famous condottieri, including Carmagnola and Piccinino, were undoubtedly of peasant origin. On the other hand, two contemporary biographers of the first Sforza, whose account is followed by Corio, give a version of their heros youth, in which neither the axe nor his low birth occur. Alberico da Barbiano, the founder of the Company of S. George, came from the village adjoining Cotignola. According to these writers, the fame of his great neighbour so inspired young Muzio that he ran away from his fathers house when only twelve years old, in the hope of winning similar glory. He fell in with some troops belonging to a Captain of the Church, Boldrino da Panigale, with whom he remained four years. During that time he won the notice of his hero, Alberico da Barbiano, who, impressed by the lads great strength and fiery nature, nicknamed him Sforza, and promised to have him trained as a soldier. When the four years were over, Muzio returned to Cotignola to visit his parents. This time he was not allowed to leave home empty- handed, and his father sent him back to the camp with four fully equipped horses, a gift which must have involved considerable wealth on the part of the donor.

The recent researches of Professor Gaetano Solieri, in the archives of Cotignola, have made a strong case for this second version of the story. His evidence shows that the Attendoli, far from being poor peasants, ranked among the leading families of their native town. As early as 1226 an Attendolo acted as ambassador for the neighbouring town of Bertinoro, when it made its submission to Bologna. Giovanni Attendolo, Muzios father, married Elisa Petrocini, who came of a well-to-do citizen family, and it is probable that her husbands social status was very much the same as her own. When Sir John Hawkwood enlarged and fortified Cotignola in 1376, the only lands suitable for his purpose belonged to Giovanni Attendolo, who consented to yield them in exchange for a yearly tribute. Meanwhile Giovanni was occupied with the building of his own family mansion, which appears to have been one of the few houses in Cotignola that were not made of wood. A document of the year 1412 records a great fire in the town, which destroyed everything save the church, the house of Sforza, the house of Lorenzo Attendolo, and two or three houses near them, which did not burn because they were of stone. Not only were the Attendoli comparatively wealthy, but they were also powerful and war-like. The peace of Cotignola was constantly broken by their feud with the Ghibelline family of Pasolini which came to a crisis in 1388, when Bartolo Attendolo and Martino Pasolini aspired to the hand of the same young lady. Sforza, who was spending the winter at home in condottiere fashion, threw himself into the fight that ensued. Two of his brothers were killed and he himself was badly wounded. Finally matters reached such a pitch that those of the Pasolini who had most deeply offended the Attendoli decided to quit Cotignola, while those who remained changed their name in order to escape the enmity of their rivals. The Attendoli were a numerous race, and Elisa Petrocini had no less than twenty-one children, all of whom seemed born with a natural aptitude for warfare. Fifteen of Muzios brothers and cousins became soldiers of some repute, the most celebrated among them being Micheletto Attendolo, who raised the mercenary standard at the same time as his cousin. He afterwards won distinction as Captain- General of the Venetian forces, in which capacity he fought against Francesco Sforza on more than one occasion. With all this the Attendoli were rough, even barbaric, in their habits. According to Giovios description, Sforzas home in Cotignola was more like a camp than a private house. The walls were hung with shields, lances and coats-of-mail instead of with tapestries. For beds there were great wooden couches without hangings or coverings, upon which a band of soldiers could throw themselves. Instead of sitting down to well-cooked meals, every one ate standing of such rough food as the men- at-arms could prepare.