Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

The noblest pleasure is the joy of understanding.

LEONARDO DA VINCI

The traditional view of Leonardos early career is that he was recognized as a prodigy in the workshop of Verrocchio, enjoyed a promising start in Florence, and then moved to Milan to become the celebrated court artist of Duke Ludovico Sforza, the ruler of the Duchy of Milan. As this book aims to show, the opposite is true. Almost from the beginning, Leonardo struggled to develop a style that rejected the formulaic Quattrocento brand of his master, Andrea del Verrocchio, but he was stymied in his efforts to finish his first masterpiece in Florence. He then left for Milan on little more than a wing and a prayer, but for many years was studiously ignored by Ludovico. It was only because of his association with the de Predis brothers that he was able to survive. Worse, when he finally did receive a ducal commissionthe famous Sforza equestrian monumentit ended in failure, whereupon he had to satisfy himself with secondary commissions, such as the portraits of Sforzas mistresses.

In fact, the reader may be astonished by the questions that still swirl around the work of young Leonardo. For example, what is the true reason that The Adoration of the Magi, the seminal work of his early Florentine period, is unfinished? And why did Leonardo decide to move to Milan, of all placesa court known more for its wealth than for the quality of its artistic endeavors? And why did Milans ruler, Duke Ludovico Sforza, ignore Leonardo for so many years? Why did all the truly important commissions that emanated from the court of Milan, such as church frescoes, monuments, and Sforza propaganda art, go to Lombard artists who were much less talented? Indeed, should Leonardo be considered a court artist at all? If he was truly Sforzas celebrity painter, the leading light of his court, then why was he not involved in the projects the duke genuinely cared about, such as the decoration of the massive Milan Cathedral, or the Certosa di Pavia monastery complex, or countless other churches, including the Santa Maria delle Grazie itself?

Even the Last Supper fresco, about which scores of books have been written, still harbors many mysteries. For example, what is the relationship between The Last Supper and the fresco of The Crucifixion, which was begun on the opposite wall at exactly the same time as Leonardo began his painting? Is there a hidden program between the two? And why is there such an obvious connection between Leonardos donor portraits on the Crucifixion and the mysterious Sforza Altarpiece, the Pala Sforzesca ?

Why have these questions not been addressed before? The answer is perhaps simpler than we might expect. Most modern authors are so focused on the centuries-old effort to physically restore the Last Supper fresco, Leonardos Milanese masterpiece, that they are almost blindsided by it. And while the latest restoration, completed in 1999, is certainly impressive from a technical point of view, its outcome is rather sobering: only some 20 percent of Leonardos original masterpiece is still extant.

The conclusion is inevitable: we no longer know what this painting looked like . Yet, there is no question that with this painting, Leonardo singlehandedly introduced the era of the High Renaissance. But how can we appreciate the work as Leonardos contemporaries saw it? Is it possible to reconstruct the fresco by other means?

This provocative book was written to answer these questions, and to offer a fascinating window on the mind of a young artist as he slowly developed the groundbreaking techniques that would transform Western art.

Art is never finished, only abandoned.

LEONARDO DA VINCI

They were, by any measure, outrageous terms. Some would have called them downright insulting. For the contract stipulated that, to begin with, the artist was expected to pay for the commission himself not just his brushes, pigments, and all other materials, but also the cost of the assistants who would be mixing the paints, prepping the panel, and applying the gesso, the preparatory coat of gypsum and glue. Worst of all, the artist would not be paid for his labors until the work was completed, delivered, and duly accepted to the patrons satisfaction. Even then, the painter would not be paid in cash, but in kindin the form of a portion of a small estate in the Val dElsa that a benefactor had bequeathed to the monastery some months before. On the plus side, the property had been valued at three hundred florins (roughly forty thousand dollars in modern currency). On the downside, half of it was supposed to serve as the dowry for the patrons daughterwhich, incidentally, the artist was expected to advance as well. And if at any time the painter decided to walk away from the commission, he would, as the friars told him, forfeit that part of it which he has done.

Outrageous terms indeedwhich suggests a few things. For one, it indicates a deep skepticism on the part of the commissioning agency, the Augustinian monks of San Donato a Scopeto, in Florence, that the artist could actually pull off the commission. Second, it suggests that the good friars would probably not have hired the painter at all had their attorney, a certain Ser Piero da Vinci, not lobbied strenuously on the artists behalf. He had good reason to do so, for the painter in question was none other than his sonan illegitimate son, to be sure, but his son, his own flesh and blood, nevertheless.

You can have no dominion greater or less than that over yourself.

LEONARDO DA VINCI

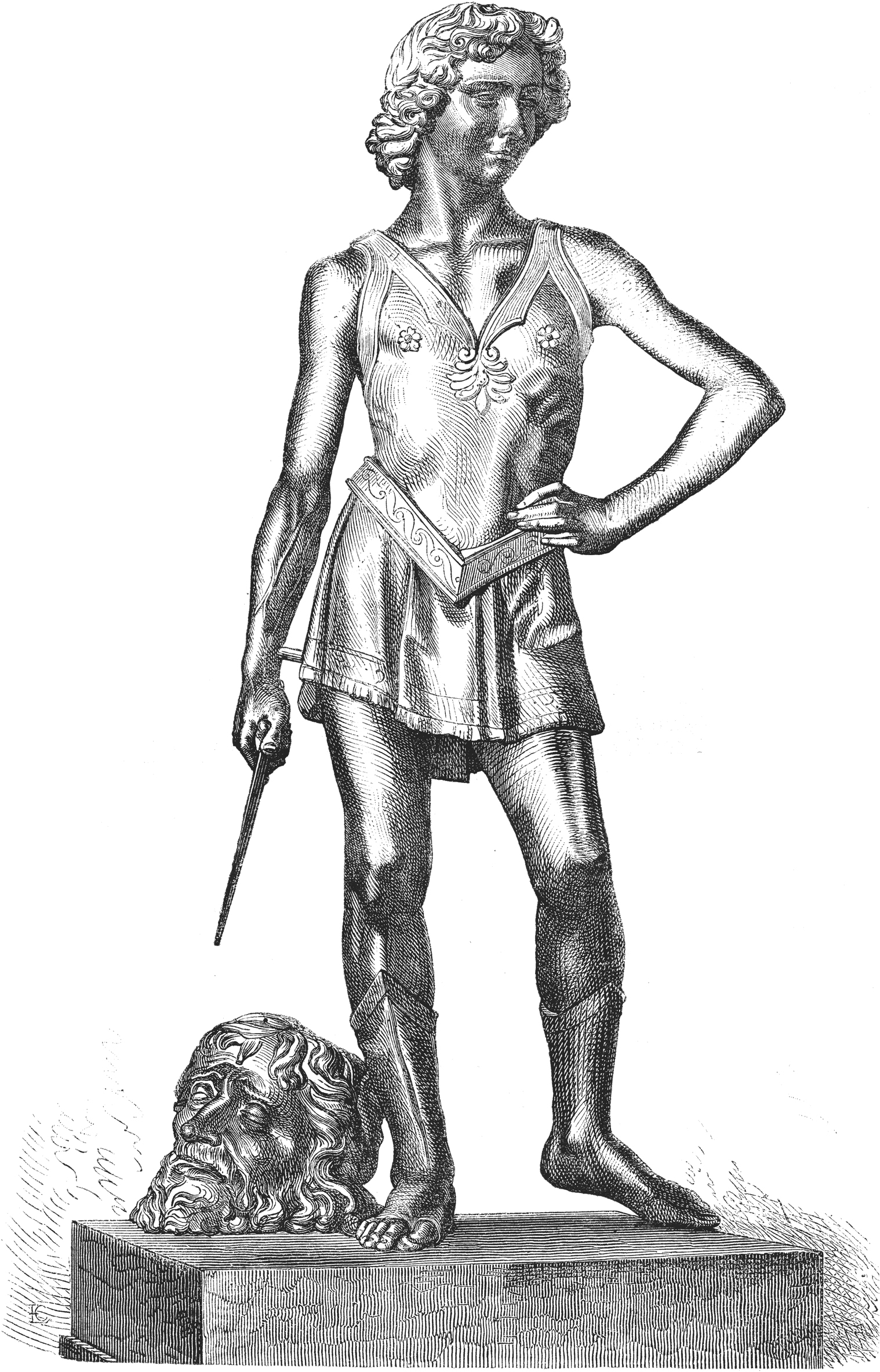

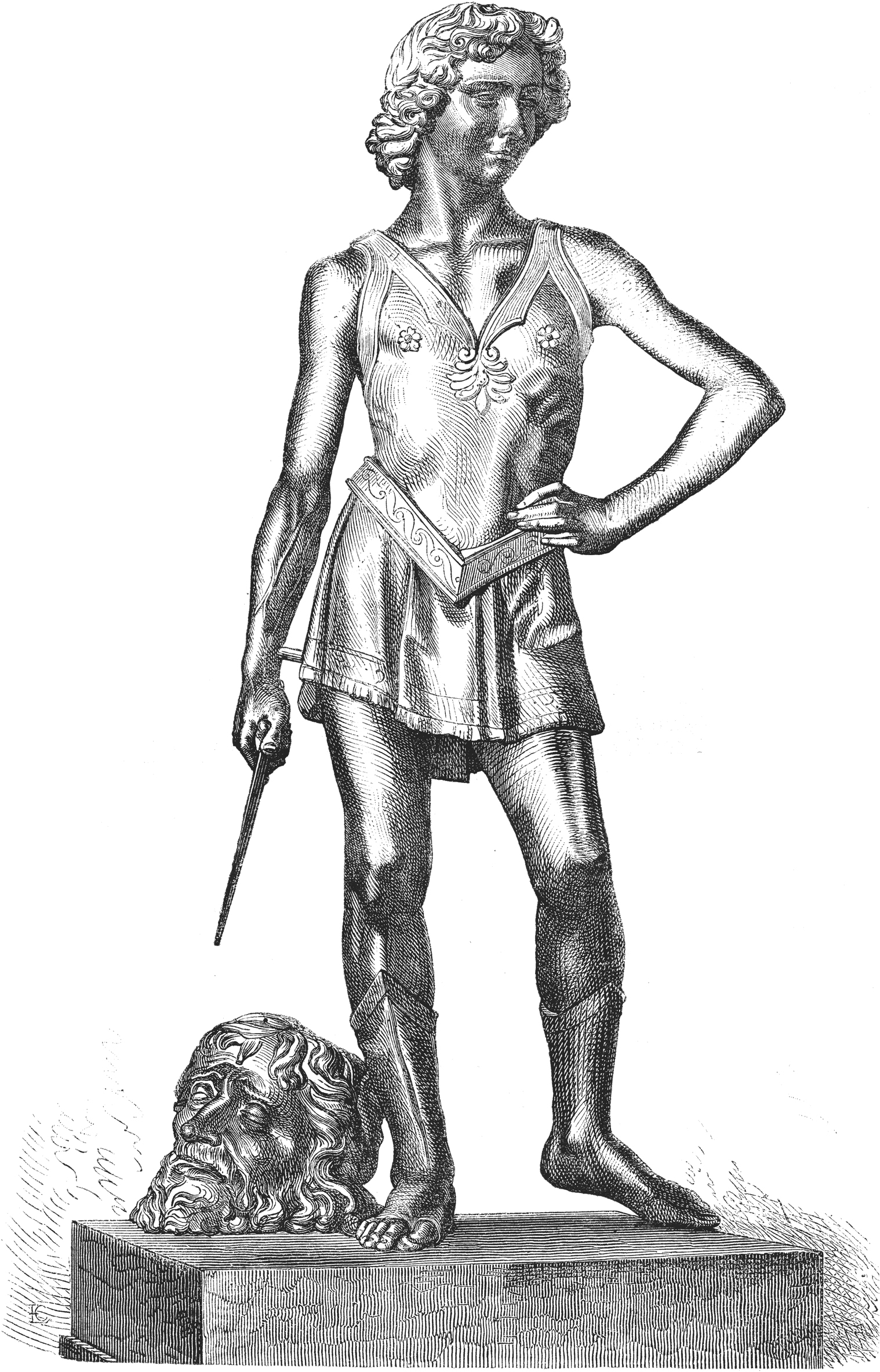

Ser Piero da Vinci recognized the talents of his young son, Leonardo, early on. Thats why, in 1466, he arranged for the boy to be apprenticed at the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio in Florence when the boy was just fourteen years of age. According to the sixteenth-century author Giorgio Vasari, one of da Vincis first biographers, Leonardo was soon recognized as a prodigy, which under normal circumstances would have meant that a bright future lay ahead of him. So, in the six years that he worked in Verrocchios bottega, Leonardo learned to draw, to prep wet plaster and wooden panels, to stretch canvas, and to grind and mix pigments in order to create paint. (Ready-made paint tubes of the type we use today would not appear until the nineteenth century.) Eventually he was entrusted with more important tasks, such as transferring a cartoon (a drawing to scale) to a plaster or wooden surface, blending colors in water-based tempera or oils (still a relatively new invention then), and finally, painting lesser elements, such as a background landscape.

Verrocchios workshop was in high demand, which meant his pupils worked on a wide range of artistic endeavors, not only painting and sculpture (in plaster, wood, or bronze), but also a variety of furnishings, such as wooden chests, chairs, and coats of arms. The studio was also called upon whenever Lorenzo the Magnificent, the Medici ruler of the city, wished to produce any of the sumptuous masques and pageants for which his rule was famous. This invariably involved all sorts of intricate stage sets and machinery, as well as costumes, tapestries, and the construction of temporary structures such as Roman-style triumphal arches. Leonardo was at the studio when Verrocchio attained one of his greatest triumphs: the completion of a huge gilded ball that, in 1471, was hoisted to the top of the lantern of Brunelleschis famous dome over the Florence Cathedral. In the process, Leonardo was thoroughly indoctrinated in Verrocchios unique brand of art: the production of lovely though somewhat soulless and formulaic figures, whether sacred or secular, whose robust disegno betrayed the masters preference for sculpture over painting.