LEONARDO DA VINCI

Books in the RENAIS SANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

Books in the RENAIS SANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

Series Editor: Franois Quiviger

Already published

Blaise Pascal: Miracles and Reason Mary Ann Caws

Caravaggio and the Creation of Modernity Troy Thomas

Hieronymus Bosch: Visions and Nightmares Nils Bttner

Isaac Newton and Natural Philosophy Niccol Guicciardini

John Evelyn: A Life of Domesticity John Dixon Hunt

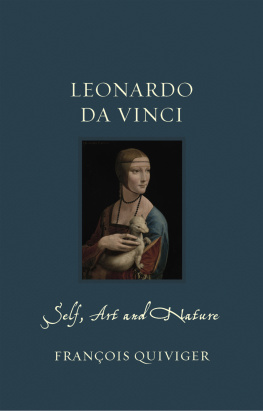

Leonardo da Vinci: Self, Art and Nature Franois Quiviger

Michelangelo and the Viewer in His Time Bernadine Barnes

Petrarch: Everywhere a Wanderer Christopher S. Celenza

Pieter Bruegel and the Idea of Human Nature Elizabeth Alice Honig

Rembrandts Holland Larry Silver

Titians Touch: Art, Magic and Philosophy Maria L. Loh

LEONARDO

DA VINCI

Self, Art and Nature

FRANOIS QUIVIGER

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2019

Copyright Franois Quiviger 2019

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 978 1 78914 107 8

COVER: Leonardo da Vinci, Lady with an Ermine, 148990, oil on panel. Muzeum Narodowe/the Princes Czartoryski Museum, Krakw photo laboratory Stock National Museum, Krakw.

CONTENTS

1 Leonardo da Vinci, An Old Man and a |outh in Facing Profile, c. 14951500, red chalk on paper.

Introduction

hough Leonardo da Vinci might be the greatest Western painter of all time, and the maker of the most expensive painting ever sold, painting occupied only a small fraction of his time. In a life spanning 67 years he produced only about twenty paintings; had he not painted, he would have been remembered as no more than an interesting and original historical character. Although popular culture has credited Leonardo with many inventions and characterized him as a universal genius, in art as in other fields he merely followed, improved and developed pre-existing traditions. His knowledge was far from universal, either. He received only a basic vernacular education, read Latin with difficulty and never attended university. Yet his life and work demonstrate that universality can be achieved outside the confines of institutional knowledge, through the possibilities granted by the visual arts.

hough Leonardo da Vinci might be the greatest Western painter of all time, and the maker of the most expensive painting ever sold, painting occupied only a small fraction of his time. In a life spanning 67 years he produced only about twenty paintings; had he not painted, he would have been remembered as no more than an interesting and original historical character. Although popular culture has credited Leonardo with many inventions and characterized him as a universal genius, in art as in other fields he merely followed, improved and developed pre-existing traditions. His knowledge was far from universal, either. He received only a basic vernacular education, read Latin with difficulty and never attended university. Yet his life and work demonstrate that universality can be achieved outside the confines of institutional knowledge, through the possibilities granted by the visual arts.

Leonardo was born in April 1452 the illegitimate son of a young notary and a peasants daughter. He spent the first years of his life in the countryside and would have remained merely a clever farm boy had his father not decided to take him to Florence and place him as an apprentice in the workshop of the most famous artists of the time. Thus it could be said that he had two masters, Nature and Art; and it was thanks to these that he produced images that changed the course of art history and gave new shape to the Western imagination.

This short biography examines the processes through which Leonardo used his understanding of art, nature and society to shape his pictorial work as well as his own persona, which, seen from the distance granted by history, is as remarkable as his artistic legacy.

A typology proposed by John Jeffries Martin advances three types of self within the Renaissance context: the communal or civic self, the prudential or performative self and the porous self. The first relates to social groups, family and lineage. Leonardos civic self encompasses the whole of Renaissance society. His family and lineage connect him to peasants and farm workers through his mother, to the Florentine bourgeoisie through his father, and the artist and artisan class through his master Andrea del Verrocchio. By the time he reaches his thirties he mingles with and becomes part of European high society as part of the entourages of kings and rulers. In other words, Leonardos civic self is a fresco of Renaissance society, from the peasant to the king.

The prudential self handles relations between the inside and the outside worlds. Within this category we might highlight Leonardos ability to adapt to varied situations: to morph into a musician, architect, painter, sculptor, costume designer, military and hydraulic engineer, cartographer and philosopher, as well as the perfect courtier ready to entertain, dance, seduce, convince and amuse or serve his lord with exemplary efficiency. Unlike other artisan- or artist-writers, such as the Frenchman Bernard Palissy or the Florentine Benvenuto Cellini, he was not particularly boastful. But, like them, he privileged experience over theory. The correspondence Leonardo left merely suggests that he adopted what he deemed the most suitable stance with which to address a given interlocutor an ability enabled by his deep and panoramic knowledge of human beings.

The porous self primarily expresses the difficulty modernday scholars experience when trying to delimit the self as an independent thinking entity. The Renaissance porous self emerges from accounts of spirits, possessions and planetary influences as well as the broad assumption, characteristic of early modern science and philosophy, that humans and the world are composed of the same elements, on the balance of which health depends. The porous self is thus best understood through Leonardos immersive relationship with nature. For him the rational and sensitive faculties of the soul delimit the thinking self but are also part of nature. The self, and indeed humans, are in continuity with the world rather than distinct from it. This porous sense of being connects to Leonardos sense of nature as a living organism comparable to the human body, as well as to his painting method, the sfumato, which gently connects things by blurring their outlines.

A great deal of what we know about Leonardo comes from the Life written by Giorgio Vasari (1550, 1568). The author reports that one day the young Leonardo collected snakes, reptiles and frogs to use in painting a shield with a Medusas head. He was so absorbed by his work that he remained indifferent to the stench of his decaying models.the mid-eighteenth century. Yet the story rings true in regard to Leonardos obsessive thirst for observing nature through graphic and pictorial means. It sounds plausible too in terms of his studies in anatomy, which would have demanded olfactive indifference to the rising stench of bodily decay. And it also convinces in terms of the research-obsessed personality we know the artist to have been an understanding that comes out of the writings he left behind, a fifth of which are extant.

Books in the RENAIS SANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

Books in the RENAIS SANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

hough Leonardo da Vinci might be the greatest Western painter of all time, and the maker of the most expensive painting ever sold, painting occupied only a small fraction of his time. In a life spanning 67 years he produced only about twenty paintings; had he not painted, he would have been remembered as no more than an interesting and original historical character. Although popular culture has credited Leonardo with many inventions and characterized him as a universal genius, in art as in other fields he merely followed, improved and developed pre-existing traditions. His knowledge was far from universal, either. He received only a basic vernacular education, read Latin with difficulty and never attended university. Yet his life and work demonstrate that universality can be achieved outside the confines of institutional knowledge, through the possibilities granted by the visual arts.

hough Leonardo da Vinci might be the greatest Western painter of all time, and the maker of the most expensive painting ever sold, painting occupied only a small fraction of his time. In a life spanning 67 years he produced only about twenty paintings; had he not painted, he would have been remembered as no more than an interesting and original historical character. Although popular culture has credited Leonardo with many inventions and characterized him as a universal genius, in art as in other fields he merely followed, improved and developed pre-existing traditions. His knowledge was far from universal, either. He received only a basic vernacular education, read Latin with difficulty and never attended university. Yet his life and work demonstrate that universality can be achieved outside the confines of institutional knowledge, through the possibilities granted by the visual arts.