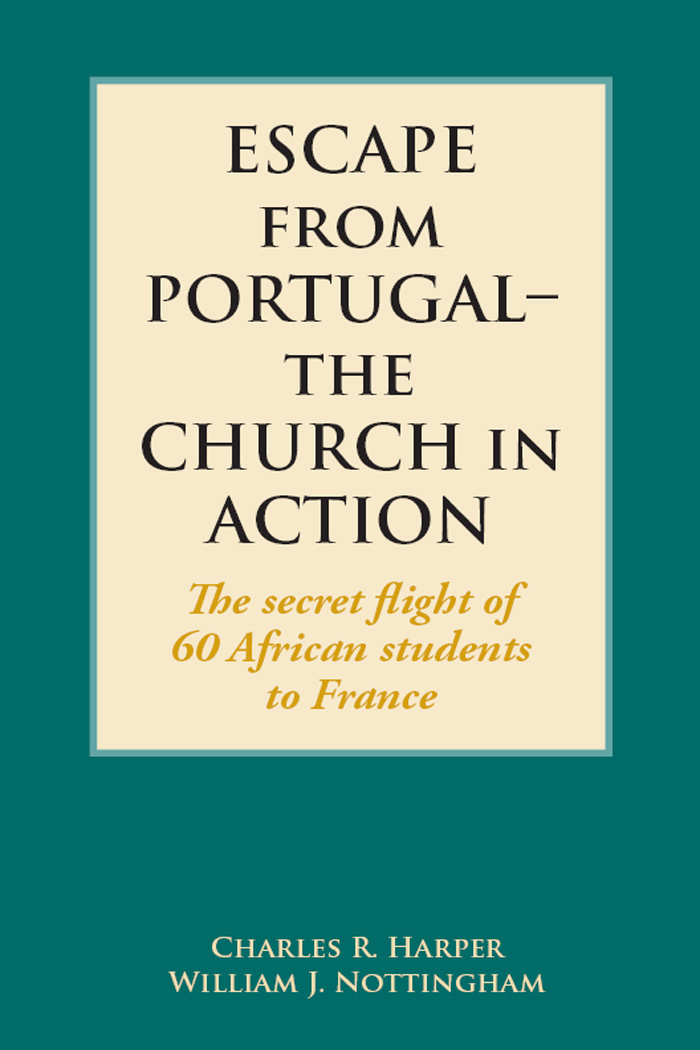

Escape from Portugalthe

Church in Action:

The secret flight of 60 African

students to France

By Charles R. Harper and

William J. Nottingham

ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI

Copyright 2015 by Charles R. Harper and William J. Nottingham

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owners. For permission to reuse content, please contact the authors at .

Photographs taken during the escape operation described in this narrative are attributed to Kimball Jones.

EPUB ISBN: 9781603500579

EPDF ISBN: 9781603500586

Published by Lucas Park

books www.lucasparkbooks.com

Contents

Introduction

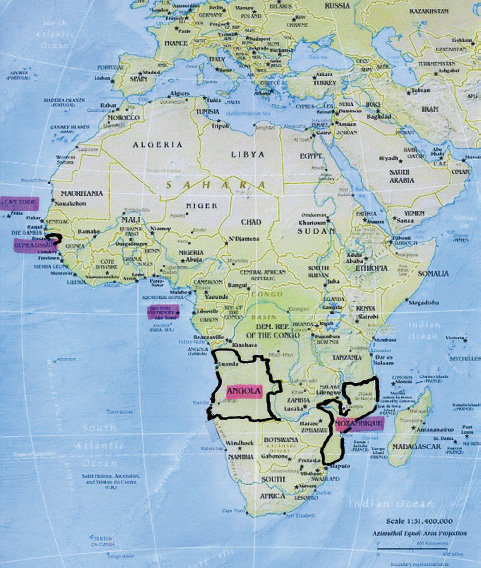

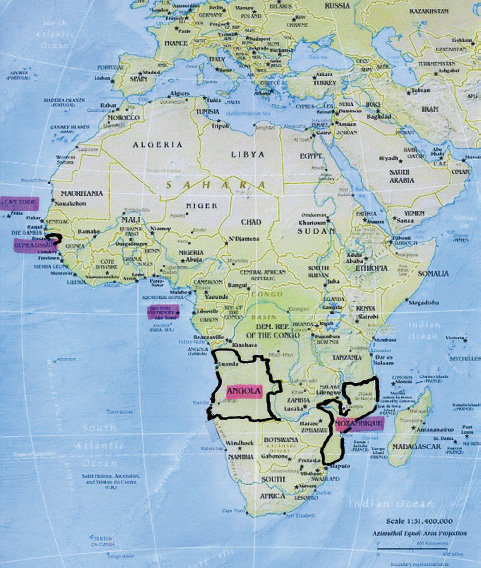

This is the story of the dramatic clandestine escape from Portugal, in June of 1961, of sixty Portuguese-speaking Africans, across Spain and into France, with the assistance of CIMADE, the French ecumenical service agency. These men and women, graduate students from Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, and So Tom and Prncipe, studying in Lisbon, Coimbra and Porto, became the future leaders of their countries after wars of de-colonization and eventual independence.

To tell this story, weBill Nottingham and Chuck Harper have chosen to quote liberally from a series of interviews we conducted with Jacques Beaumont over the years. As the general secretary of CIMADE (1956-1968), it was he who led and energized this secret operation in mid-1961, at the request of the World Council of Churches. We were both fraternal workers assigned by our US churches to work with CIMADE at the timeBill from the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) and Chuck by the United Presbyterian Church USA. We were thus intimately involved with CIMADEs aims, humanitarian action and specific programs among the immigrant population in France. In developing the following narrative, we also benefitted from the detailed recollections recorded by the three American theological students who had been recruited during their summer in France to drive the automobiles with the Portuguese-speaking (lusophone) Africans across Spain and into France: Kim Jones, Dave Pomeroy and Dick Wiborg.

Jacques Beaumont, begins the narrative:

When I met Joaquim Alberto Chissano, the president of Mozambique, at the United Nations in 1988, he said to me: This operation advanced the process of decolonization of the Portuguese-speaking colonies by ten years. It allowed for a whole generation to find the ways and means to prepare themselves academically and to organize themselves in the exterior, to seek financial support which is always so important to achieve decolonization, and to diversify this support. The operation, recounts Beaumont, lasted a long timemuch longer than the months we had spent together getting ready for it and carrying it out. In logical order, they comprised the preparation of the operation before it actually began. Then the operation itself was carefully divided into three stages: the Portuguese, the Spanish and the French. Afterwards, however, its sequels lasted for many years.

When he first approved of plans for CIMADE to attempt the Angolan Operation, Willem A. Visser t Hooft, General Secretary of the World Council of Churches, said This is the Church in action!

1

A call for help from Lisbon, African students, the World Council of Churches and CIMADE

By May of 1961, the growing number of graduate students from the provinces, as the Portuguese government called its colonies, was thoroughly galvanized by the Portuguese vengeful repression of armed rebellion occurring in Angola since January. Their meeting places, in such social centres like the Clube dos Martimos or the Casa dos Estudantes do Imprio (House of the Students of the Empire) in Lisbon, came into sharp surveillance by the Portuguese political police. They were also increasingly apprehensive over harassment by the police to which they were subjected. Many had their passports revoked. Secretly, decisions were taken by the most politicized to leave the countryillegally if necessaryand to head for France and elsewhere. The incipient independence movements had neither sufficient financial means nor an organizational infrastructure in Europe to enable these students to escape Portugal.

Thus, one of the organizers of the group, Pedro Antonio Filipe, made an urgent appeal to the World Council of Churches, based in Geneva. Pedro was related to the World Student Christian Federationthe WSCFand was part of the 15% of the students who had received primary and secondary education in Angola at schools run by Baptist, Methodist, and Congregational missionaries from the U.K., Canada and the USA.

A mission executive for Africa of the Methodist Church in the USA, the Rev. Melvin Blake, stopping in Lisbon to visit some of these Methodist students in early May, 1961, was entrusted with the Angolans urgent request, made on behalf of students from all five of the Portuguese colonies. The students said, If you dont get us out of Portugal, youre not Christian! Some other studentsSilvio de Almeida, a medical student among themwho had left Portugal a year earlier to continue their studies in the rest of Europe, confirmed the request to the General Secretary of the WCC, the Dutch theologian Willem Visser t Hooft, informing him of the daily pressures being brought by the Portuguese authorities on the students and asking for the solidarity of the churches to help them to get out rapidly.

The World Council of Churches in Geneva

The WCC, founded in 1948 at a General Assembly in Amsterdam, had been an ecumenical movement prior to and during WW II. Its pioneer founders were facing and resisting the fascist ideology of Hitlers Germany. The active engagement of Christian men and women across Europe, including ecumenical leaders in Geneva, were tireless in protecting citizens and refugees and in acting to defeat the Third Reich. Cooperative Germans were mainly participants of the so- called Confessing Church, after the Barmen Synod of 1934. This commitment prepared ecumenical leaders such as Willem Visser t Hooft, the Dutch first General Secretary of the WCC, to be particularly sensitive, years later, to the request of the Portuguese-speaking students in Portugal to help them escape to freedom. For example, his moral authority and leadership, exercised along with that of Madeleine Barot and other French lay and pastors, all influenced by Swiss theologian Karl Barth, produced the publication, in 1944, of the powerful Thses de Pomeyrol. The Thses amply reflect the ecumenical clarity at that time concerning the responsibility of Christians to protect the most vulnerable under the German occupation in several European countries and to resist the policies of the Nazis.

Responding to the students appeal, the WCC turned to Paris-based CIMADE, an ecumenical service agency of the French Protestant Federation, asking that it take on the responsibility of organizing an escape by these men and women from Portugal to France. At the time, Madeleine Barot, one of the founders of CIMADE and still a member of its