2015 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015951273

ISBN 978-0-252-03967-6 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-252-08117-0 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-252-09776-8 (e-book)

Note on Orthography

Because Cape Verdean Creole has never been recognized officially, its orthography varies, including the name of the language itself. The two most common spellings are Kriolu and Crioulo . I opt for the former because it is most common in Lisbon. In part, this spelling stems from a particular politics related to the island of Santiago, often in distinction or opposition to the island of So Vicente. Linguists and Kriolu activists have developed and sporadically implemented the orthographic system of the Unified Alphabet for the Writing of Cape Verdean (ALUPEK). However, very few of my interlocutors practiced ALUPEK, even those who support it politically. Therefore, many words, in practice, contain options for c / k , s / z , n / m , among other variations. This is all to say that Kriolu fosters neologisms, and rappers, the main sociocultural group in focus in this book, exploit this structural opportunity.

I use Creole to refer to Creole language, in general, and to the social, cultural, historical, and other related phenomena conventionally indicated by the term. I use Kriolu to refer more particularly to aspects of Cape Verdean language and identity. Moreover, I am trying to assert the importance of Kriolu and Creole as significant and complex concepts through the use of capitalization as would be the case with English or, more pertinent, Portuguese .

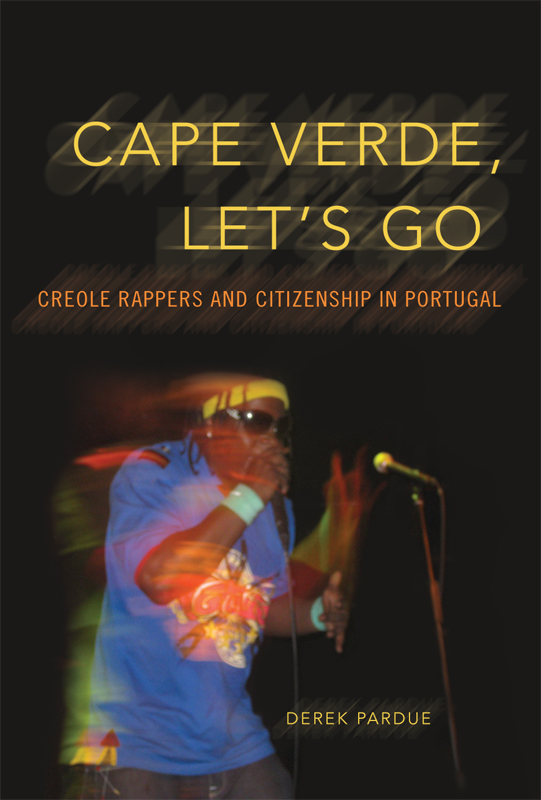

Introduction

When one is standing at the cliffs at the Roca Cape (Cabo da Roca, ), it is easy to imagine that one is at the end of the world. The sixteenth-century Portuguese writer Lus Vaz de Cames famously describes that this is where land ends and the sea begins. The constant gusts sweeping across the ocean dramatize the act of historiography, the recording and archiving of Iberian, European, and African journeys at this southwestern extreme of Europe. One can imagine the excitement of modernity on the threshold of discovery. I witnessed that vast sea, an immensity that elicits reflection on the whole nature of things.

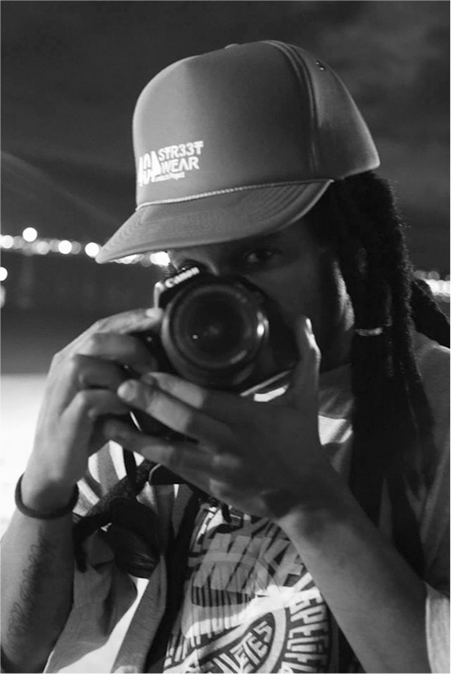

A couple of years later, I recalled those moments of seemingly floating above the ocean, navigating time in individual imagination, as Corsino (Uncle C) ( The clotheslines swayed under a stiff breeze as Uncle C checked his cell phone to search for funds to send to his family in Cape Verde and the Azores. Meanwhile, I looked out under a clear, cobalt-blue sky onto the Bairro de Santa Filomena (BSF) dwellings. Night was falling, and I felt I had come to another sort of precipice, increasingly aware of the complexity of migration webs and networks that make up the idea of being Portuguese and being Cape Verdean. I left for Praia, the capital city of the Cape Verde archipelago the next morning.

FIGURE 1 . Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point of Europe. Photo by author, 2015.

I had begun to realize that Creole, as a sentiment and history, is both as expansive as the ocean and as intimate as colonialism. In scholarly circles, Creole is a by-product of colonialism and a serendipitous identity category of seemingly everyone in the fast-paced globalized world. Watching Uncle C at work on his phone and listening to the Cape Verdean braggarts in the alleyways below, I began to see the story of Kriolu, the Cape Verdean language-identity, as a Creole interruption and, thus, a contingent break from the mimesis of Portugals soft power of inclusion. Cape Verde, Lets Go: Creole Rappers and Citizenship in Portugal is about the history of encounters and the politics of difference. It is about an Eastern Atlantic Creole that deserves consideration among scholars of (post)colonial citizenship.

A Shift in Demographic Tide and the Steadfastness of Paradigm

Portugal was once a giant of European conquest and benefactor of colonial largesse. Thus begins an old Iberian tale that produced decades of nostalgic public policy and state ideology during the waning generation of the late nineteenth-century monarchy, the early republic, and the Antonio Salazar dictatorship of the twentieth century. Whether the key words are discovery and civilization or remittances and diaspora (Feldman-Bianca 1993; Baganha 1999), the idea of Portugal has been until relatively recently a concept of emigration and spreading out. The notion of Lusophone space is far from negligible. According to Jorge Fernandes Alves (1999), with over two hundred million speakers and occupying over four million square miles on four continents, Portugueseness, in some fashion or another, represents 7 percent of the globes land mass.

FIGURE 2 . Uncle C. Reprinted by permission of Corsino furtado.

to most languages, Portuguese varies widely between continents, and, of course, the Creoles of Cape Verde, highlighted in this book, along with those of So Tom e Prncipe (a smaller archipelago off the coast of Gabon), Guinea-Bissau, and Curaao, disrupt even further any sort of notion of homogeneity. It is in contrast to the ideology that Portugueseness (and by extrapolation, Englishness, Frenchness, and so on) is by nature disseminating and cohesive that I wrote this book. The particularities of Portuguese colonialism and the unique relationship between Cape Verde and Portugal reveal a general lesson: citizenship is a dynamic encounter in which hybridity and distinction are complementary, not oppositional.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.