DEDICATED TO

Kerry, Emma and Aeryn

CONTENTS

Clock Tower, V&A Waterfront

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Putting this book together was a great adventure and an amazing learning experience, and would not have happened without a group of very talented people. It gives me great pleasure to acknowledge those who made it possible.

Phil Massie, you are a great friend and photographer. Without your attention to detail and perfectionist way of working, this book would not have happened. Thank you for always making time in your hectic schedule and for sharing my vision.

Anne Clarkson, thank you for all your research and writing. I will miss our meetings at the Archives and your emails about the interesting things you discovered. This book belongs to you as much as anybody else.

My thanks to the staff at the Western Cape Archives and Records Service Erika Le Roux, Achmat Smith, Ebrahim Kenny and Lunette Lourens for making the research at the Archives such a pleasure. You were always willing to help and to go the extra mile without question. Without your help, this book would have taken a few more years to complete.

A special thank you to Jaco van der Merwe: since day one, more than ten years ago, you have been behind me and supported my ideas. Without your enthusiasm, this book would never have been. You are a great asset to the Archives and I think you are the only person who might love these old photographic collections more than I do.

To the team at The Aerial Perspective Anthony Allen, Keith Quixley, Lucia Bellairs your beautiful aerial photographs added the finishing touches that I needed. Its always a pleasure working with such talented professionals.

At Random House Struik, my thanks go to Pippa Parker and Janice Evans, for seeing and believing. You and your production team managing editor Roelien Theron, editor Alfred LeMaitre and editorial assistant Alana Bolligelo were fantastic to work with.

Thanks to Mike Ormrod, not just for keeping me employed all these years, but also for always helping with, and supporting, my sometimes obsessive fascination with old glass plates and photographs.

And, last but not least, thanks to Seppi Hochfellner, for added inspiration.

Vincent Rokitta van Graan

FOREWORD

My interest in photography began at an early age. My father was an amateur photographer, and, although he gave up his darkroom when I was very young, the enlargers, developing trays and chemicals made a big impression on me.

After completing a three-year BTech Diploma in photography at the Pretoria Technikon, I moved to Cape Town in 2001. I had the impression that there would be lots of overseas and local photographers looking for assistants, and that this would be a great way to gain work experience. After working as an assistant and freelance photographer for a while, I became more involved in the editing and printing side of the photographic process, and started working for a professional photography laboratory in the city. I specialise in large-format photographic printing that combines the traditional darkroom with the technology of modern digital photography. I am able to produce some of the highest-quality photographic prints in South Africa, and I work with a range of artists and photographers from all over the world. Together we print everything from full exhibitions and installations to one-off, limited-edition archival-quality photographs. Even though I do not get much time for my own photography any more, there is nothing else I would rather be doing, and I dread the day when my darkroom and chemicals finally become obsolete.

Since the first time I saw a glass-plate negative, I have been fascinated by the process. The photographers of the past had to have great patience to produce a photograph. Anybody who has ever used an 8 x 10-inch or 4 x 5-inch bellows camera will tell you not only how difficult they are to use, but also that the quality they produce is better than that of most modern digital cameras. I have been trying to buy and build up a collection of glass plates of my own. I go to antique markets and shops and am constantly on the lookout for where I might find more. However, most of the plates I find are badly damaged and faded from poor storage and exposure to light.

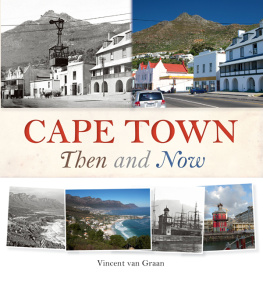

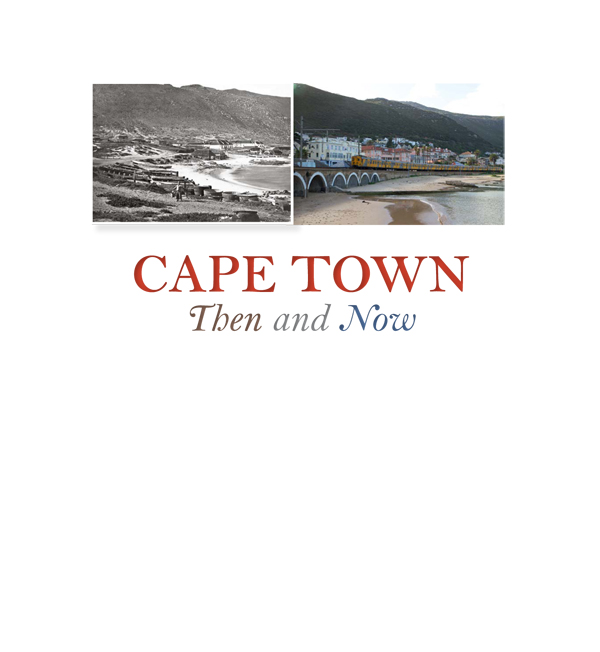

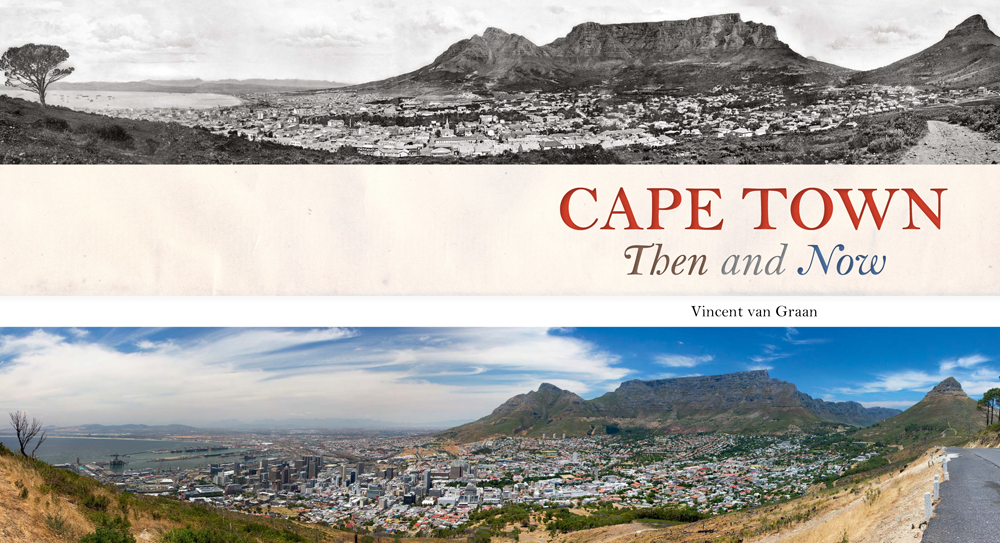

Some years ago, while doing research at the Western Cape Archives and Records Service, I came across the most beautifully photographed and best-preserved photographic collections I had ever seen. The quality of these photographs, especially the work of Arthur Elliott, Edward Steer and Thomas Ravenscroft, is on par with the best photographic images produced today. I decided then that I wanted to produce a book showcasing some of these photographs of Cape Town, combined with images of what these landscapes look like today.

Cape Town is one of the most beautiful cities in the world, and the backdrop of Table Mountain and the Peninsula make it ideal for such a comparison. In many cases, using the mountain as a reference, it is possible to find almost the exact spot where these old masters of photography set up their large cameras.

Precious few of the photographs and plates in the Archives are dated, but in most cases it was possible to determine more or less when they were taken from where they are in the collections or by comparing them with those that do have dates. Most of the photographs in the book were taken between circa 1880 and circa 1930, although there are a few, like the ones of the Roeland Street jail (now the Western Cape Archives and Records Service), from the 1970s.

After retouching and working with these photographs for years, I enjoy them more than ever, and I hope that every reader will appreciate how fortunate we are to have such a beautiful collection of photographs.

VINCENT ROKITTA VAN GRAAN

PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTIONS IN THE WESTERN CAPE ARCHIVES

The Western Cape Archives and Records Service, formerly known as the Cape Archives, preserves a number of important historical collections of photographs dating back to the late nineteenth century. This book includes numerous works from the collections of the photographers described below.

ARTHUR ELLIOTT was born in America in 1870 and grew up in great poverty. He made his way to South Africa in the 1890s, initially trying to make a living in Johannesburg. He fled to Cape Town at the time of the Second Anglo-Boer War (18991902), and it was then that a remarkable stroke of luck led to him embarking on a photographic career.

A friend gave him a quarter-plate camera, and he began photographing Boer prisoners at the prisoner-of-war camp in Green Point. His photographs were popular, and he made a good living selling prints. Encouraged, he opened a studio in Long Street, where he remained for most of his working life.

Elliott was particularly interested in the history of the Cape and its architecture, and his many photographs of picturesque scenes record much that was soon to disappear.

A number of exhibitions of his work were staged, the first during the Union celebrations of 1910. His second exhibition in 1913 was entitled The Story of South Africa told in 800 pictures, and the subject of the third exhibition in 1926 was Old Cape Colony. His last exhibition, in 1930, was the most ambitious and contained over a thousand photographs.

Next page