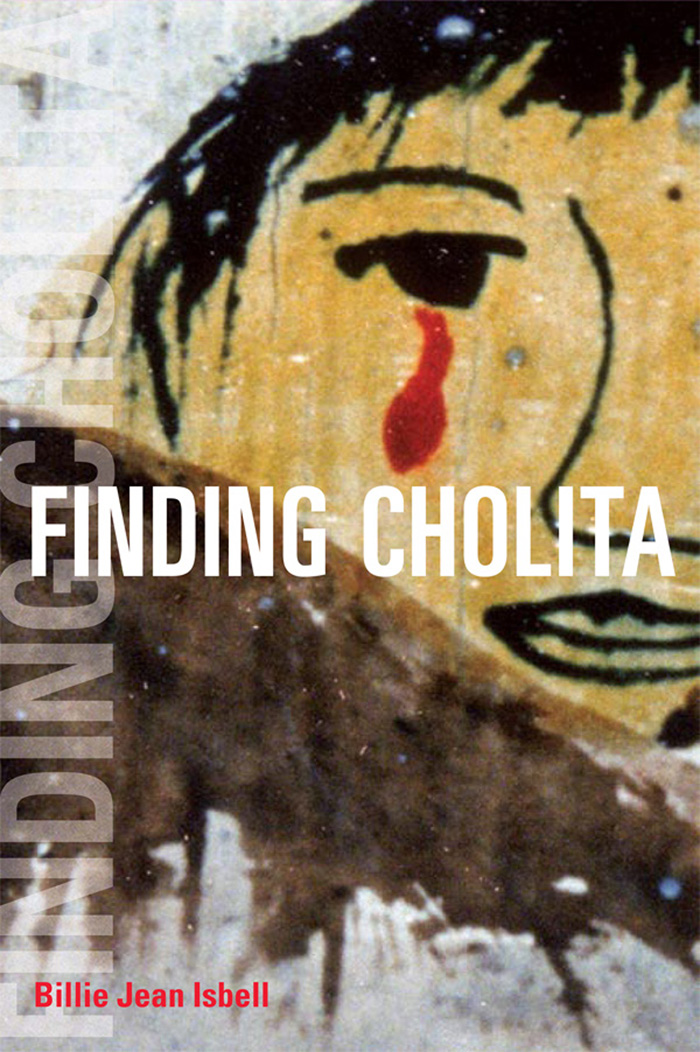

2009 by Billie Jean Isbell

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Isbell, Billie Jean.

Finding Cholita / Billie Jean Isbell.

p. cm. (Interpretations of culture in the new millennium)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-252-03412-1 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-07606-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. AnthropologistsFiction.

2. Human rightsFiction.

3. Latin AmericaFiction.

4. Sendero Luminoso (Guerrilla groupFiction.

I. Title.

PS3609.S26F56 2009

813'.6dc22 2008036542

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE: WHY TURN TO FICTION?

Over the forty years that I have been conducting research in Peru, there have been events that have haunted me that I have not been able to forget nor write about in the venues offered in anthropology. In order to gain closure and provide a form of therapy for myself, I have turned to fiction. During the twenty years that I focused on violence, I absorbed the horrific stories told to me and found myself developing disabling infirmities. For example, as I was struggling with whether to publish the testimonies of victims, I was rendered speechless by reoccurring lesions on my tongue that required surgery.

My research has been centered in the southern region of the department of Ayacucho, Peru, that was terrorized by the Shining Path from 1975 to 1992, when the leader of that movement, Abimael Guzmn, was captured. This account of those years is a combination of ethnographic description and ethnographically grounded fiction. Nevertheless, the details and dates of the war are accurate.

I began my research in Peru in 1967 as an undergraduate writing an honors thesis on the civil-religious hierarchy in the village of Chuschi, Peru. During my first fieldwork, I settled into the village with my husband, my two-year-old daughter, and my mother. The often comical difficulties of that first encounter are described in the introduction of To Defend Ourselves, the ethnography of the community of Chuschi first published in 1978. Returning to Chuschi through the decades that followed has allowed me to document the many transformations and changes that have taken place, not only in a remote Andean community that was thrust into the spotlight of history, but transformations in myself as well.

The insurgency, Shining Path, chose to announce their war against the Peruvian state in May of 1980 by burning the ballots in Chuschi for the first national democratic election in seventeen years. That election was also the first that allowed illiterates to vote. That action placed the region in the epicenter of a twenty-year war that cost seventy thousand lives, most of whom were Quechua-speaking peasants. At the time, no one (including me) took the burning of the ballots seriously. No shots were fired, the ballots were replaced, and the election occurred the next day. But later I learned that the burning of the ballots was carried out by teachers and students of the secondary school as a long-term strategy of Shining Path that began in 1975.

When I returned to Chuschi in 1975 I intended to establish a bilingual Spanish/Quechua program in the primary schools with funding from the Ford Foundation and sponsorship of the Ministry of Education. At the time I was puzzled by the opposition from some of the schoolteachers, because in previous years they had been in favor of bilingual education. Later I realized that control of the schools by Shining Path was the vehicle for ideological indoctrination and recruitment for the war to Establish the New Democracy in Peru. But, rather than a new democracy, Shining Path evolved into a rigid, hierarchical death cult that worshiped Abimael Guzmn, the philosopher turned revolutionary leader who had taught at the University of Huamanga in the city of Ayacucho. He and his followers won the ideological battle that raged in the 1970s between various political factions. Guzmn went underground and Shining Path leadership traveled to China during those years for indoctrination and training in guerrilla warfare before they began the war in earnest in 1980. The heaviest casualties occurred in the southern department of Ayacucho between 1983 and 1985. By the time the war spread to Lima and other parts of the country, it is estimated that Shining Path had close to ten thousand combatants.

As a footnote to this novel, Id like to mention that Guzmn has been in jail since his capture in 1992, and ironically, he shares a special prison with his arch-enemy, Vladimir Montesinos, the feared right-hand man and head of intelligence who sanctioned numerous massacres under President Alberto Fujimori. Both Montesinos and Fujimori fled Peru within a few months of each other, the president to Japan in November of 2000 and Montesinos to Venezuela a short time later when his own videotapes showing him bribing officials made national news. He was captured in Venezuela in June of 2001 while waiting for plastic surgery to disguise his appearance. After Guzmns capture, the insurgency faded and only a few hangers-on continued in the coca-growing rain forest region protecting the drug traffic. Guzmn, age seventy-two, is still in prison and has received government permission to marry his second in command, Elena Iparraguirre, age fifty-nine, known as Comrade Miriam, who is also incarcerated.

Alice Woodsley, the narrator of this novel, is a fictionalized anthropologist whose voice grew out of my experiences and those of my women colleagues. The story begins as Alice initiates her career as a young, nave fieldworker who gradually finds herself entrapped in a growing tornado of violence. The descriptions of the violence are based on interviews with survivors that I conducted during the 1980s and 1990s, when I found myself with a corpus of material that presented a terrible dilemma. What could I publish? How could I fulfill the responsibility of protecting the survivors I had interviewed? What responsibility did I have to anthropology? To wider political issues? This novel addresses and gives voice to those issues. I rewrote the manuscript several times, struggling with voice, finally settling on telling this story in the first person, even though it is perhaps the most difficult voice in which to write. I concluded it was the most appropriate voice for a narrative about what happens to an anthropologist who does fieldwork in a dangerous place. Two other motives guided this book. I wanted to depict how anthropologists can move across ethnic and class boundaries within a society and I also wanted to describe how a researcher can get caught in power struggles she did not foresee.

Some readers might ask, But if most of the accounts are true then why present them as fiction? One of the most obvious reasons is to protect people I have interviewed from possible harm. But others might ask, Hasnt enough time passed? Arent people safe now? By official accounts the war in Peru ended in 1992 with Guzmns capture, but disappearances continued after that date. The families of the disappeared do not feel that the environment in the department of Ayacucho is safe. Many believe they are still under surveillance due to their continuing political actions for personal and legal closure. The mechanisms for such surveillance are still in place. Nor do the victims of gang rape by military personnel feel safe, and they continue to relive their traumas. Nevertheless, the 2008 trial of ex-president Alberto Fujimori for corruption and ordering death squads along with trials and convictions of four death squad members give hope to families of victims. In addition, the National Association of Families Abducted, Arrested, and Disappeared has opened a Museum of Memory in the city of Ayacucho so that the past is not repeated.

![Communist Party of PeruCommunist Party of Peru - Shining - The Collected Works of the Communist Party of Peru. 1968-1999 [Warning: Hate Speech and Negationism]](/uploads/posts/book/267146/thumbs/communist-party-of-perucommunist-party-of-peru.jpg)

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.