James FitzGibbon

Defender of Upper Canada

by Ruth McKenzie

Copyright Ruth Isabel McKenzie, 1983

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press Limited.

Editor: Blaine R. Beemer

Design and Production: Ron and Ron Design Photography

Typesetting: Q Composition Incorporated

Printing and Binding: Laflamme & Charrier Inc., Quebec, Canada

The publication of this book was made possible by support from several sources. The author and publisher wish to acknowledge the generous assistance and ongoing support of the Canada Council and the Ontario Arts Council.

J. Kirk Howard, Publisher

Dundurn Press Limited

P.O. Box 245, Station F

Toronto, Canada, M4Y 2L5

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

McKenzie, Ruth.

James FitzGibbon: defender of Upper Canada

(Dundurn lives)

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-919670-70-9 (bound). ISBN 0-919670-71-7 (pbk.)

1. FitzGibbon, James, 1780-1863. 2. Soldiers Canada Biography. 3. Canada Officials and employees Biography. I. Title. II. Series.

FC443.F57M44 1983 971.030924 C84-098202-X

F1032.M44 1983

James FitzGibbon

Defender of Upper Canada

by Ruth McKenzie

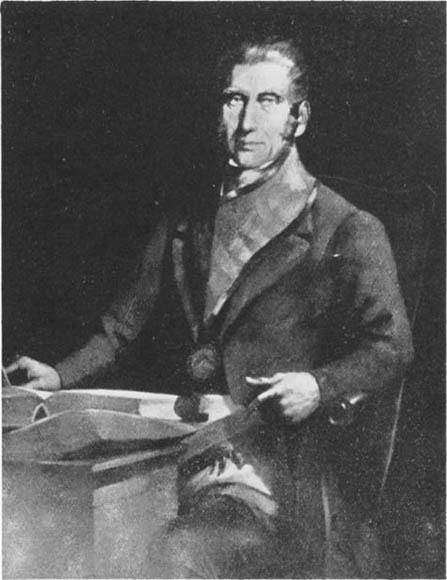

FitzGibbon in Masonic garb

Contents

Acknowledgements

Material for this biography originated mainly in manuscript documents in the Public Archives of Canada, the Archives of Ontario, the Metropolitan Toronto Library and the Public Record Office of London, England. I am grateful to these institutions for allowing me to examine their files and for the courtesy of their personnel. I wish to thank also the Vestry Office of the Cathedral Church of St. James, Toronto, for permitting me to check early baptismal and burial records, and the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society of Buffalo, New York, for providing information on Dr. Cyrenius Chapin.

In tracing James FitzGibbons Irish background, I received generous and valuable assistance from the Right Honourable Desmond Fitz-Gerald, Knight of Glin; John FitzGibbon and his daughter Mary, of Glin, Ireland; Robert Cussen, Newcastle West, Ireland; Edward Keane, formerly of the National Library of Ireland, Dublin; and from officers of the Genealogical Office, the Public Record Office and the Registry of Deeds, Dublin. My very warm thanks go to Major-General Sir Edmund Hakewell-Smith, Governor of the Military Knights of Windsor, and to Colonel and Mrs. A. E. Clark, through whose courtesy I was privileged to visit a military knights house in Windsor Castle; also to Mrs. Elliot FitzGibbon of Ashtead, Surrey, England for her friendly assistance and hospitality.

Of the many Canadians who assisted me in various ways, I can mention only a few. I am particularly indebted to the following: the family of the late C. Gwyllym Dunn of Ste Ptronille, Quebec, great-great-grandchildren of James FitzGibbon, who generously gave me access to all the FitzGibbon memorabilia in their possession; Professor J. K. Johnson of Carleton University, Ottawa, for his early encouragement to write the biography of James FitzGibbon; Lorna Proctor, Archivist of the Womens Canadian Historical Society of Toronto, for putting the FitzGibbon papers in the Societys collection at my disposal; and George Waters, formerly Curator of Fort York, for showing me around old Fort York and giving me documentation on the early days when FitzGibbon lived there. To all of the above, my sincere thanks and appreciation.

Ruth McKenzie

Chapter One

Introduction:

The Hero

as Public Servant

One of the ironies of history is that James FitzGibbon, the hero of the Battle of Beaver Dams in 1813, is now remembered, if at all, as the British officer to whom Laura Secord delivered her warning of the impending American attack. There is the irony also that FitzGibbon, who was one of the first to sense the danger of armed rebellion in 1837, who led the attack on the rebels at Montgomerys Tavern and who was credited by the citizens of Toronto for saving the city from the rebels, has been overshadowed in accounts of the rebellion by Sir Allan MacNab, the colourful and dynamic politician who actually served under Colonel FitzGibbon on the march to Montgomerys.

In the decade preceding the rebellion, James FitzGibbon, then clerk of the House of Assembly in Upper Canada (Ontario), was the object of more than one vitriolic attack by William Lyon Mackenzie in the pages of his Colonial Advocate. Mackenzie saw FitzGibbon as one of the snug little nest of clerks and other public servants for hire

Mackenzie was noted for exaggeration, but here he spoke the truth. FitzGibbon held those offices and more, and he owed his positions to two lieutenant-governors, Sir Peregrine Maitland and Sir John Colborne. It was Maitland who first appointed FitzGibbon justice of the peace, Home District, and it was Maitland who made him clerk of the House of Assembly and registrar of the Court of Probate. FitzGibbon retained those positions under Colborne, and was entrusted with other responsibilities as well.

Despite the patronage of the two lieutenant-governors, FitzGibbon never succeeded in gaining entrance to the inner circle of government. His political sympathies were appropriately conservative, and his loyalty to the Crown unquestioned, but he remained an outsider to the governing clique that became known as the Family Compact.

James FitzGibbons struggle for advancement began in the British army, where he was, even then, an outsider Irish, poor, and lacking the military tradition. In the eighteenth century, the Irish were not viewed favourably by the British army. Until 1756, no Irishman was accepted as a volunteer in the army, and no Irish Catholic until 1799. As the son of a poor man, James could not buy an officers commission. He had to start at the bottom of the military hierarchy and depend on his own wits for promotion, which meant impressing his commanding officers. In this, he succeeded very well, but only up to a point.

When FitzGibbon became a public servant in Upper Canada, his career was conditioned by the system of patronage and appointments that prevailed. Like all public servants he had to accommodate his talents and efforts to the circumstances of the time. Thus his career illustrates the way in which the public service of Upper Canada operated.

Two questions of particular significance arise. Why was FitzGibbon unsuccessful in obtaining an important government post, such as he desired? And to what extent was his career limited by his place as an outsider a person born outside the province, and with no United Empire Loyalist connections?

For reasons that will emerge as FitzGibbons life story unfolds, the man who enjoyed favours from two lieutenant-governors in the 1820s and early 1830s experienced extreme frustration in the years preceding the 1840 Act of Union and those immediately following. Strangely enough, James FitzGibbon rounded out his life in Windsor Castle.