PREFACE

The last twenty-five years have witnessed a remarkable resurgence of interest in the medical writers of Antiquity. Not since the sixteenth century has there been so much attention given to the medical classics, or so much argument over the elucidation of ancient medical theories. Whole conferences have been devoted to Hippocrates, to Galen, and even to lesser Latin medical authors; and philologists, historians, and philosophers have joined physicians in investigating their medical past. Previously unknown texts, in both Greek and Latin, have appeared in print for the first time, and the greater accessibility of Arabic manuscripts has contributed to the rediscovery of several treatises by Galen and by Rufus of Ephesus which had long been thought lost. For all his failings, Karl Gottlob Khn has not been entirely dethroned.

Since good editions of Galenic texts in Greek are not abundant, it comes as no surprise to discover that little is known about the transmission and manuscript tradition of the Galenic Corpus. There is no history of the text of Galen to set alongside the magisterial survey of Galens influence by Owsei Temkin, On his competitors and the manuscripts they used there is largely silence.

This lack of interest on the part of classical scholars may perhaps be explained by a prejudice against an author whose Greek was not only late but also, at times, forbiddingly technical. Yet it should not be forgotten that, as long ago as 1905, Hermann Diels and his collaborators at the Berlin Academy had furnished the student of the Galenic tradition with a priceless tool, an excellent catalogue of the manuscripts of Galen in Greek, Latin, Arabic and Hebrew. Nor was the Renaissance fortuna of Galen attractive to those scholars who were concerned with the rediscovery of the classics in the years from Petrarch to Politian, for their eyes were fixed on more literary texts. Furthermore, the first printing of a genuine work by Galen in its original Greek was not until 1500, and of the first complete edition not until 1525, by Aldus son-in-law and successor, and hence they failed to attract the attention of the historians of early printing. Galen, whatever his significance for medicine, came to have little interest for philologists or historians of the classical tradition.

That there might be life after Diels was first shown by Richard Durling, whose list of additions and corrections, published in 1967, revealed a surprisingly large number of errors and omissions in the Katalogs reporting of Latin manuscripts. Still more recently, Nigel Wilsons investigations into the activities of the scribe Iohannikios have radically altered the dating of many Greek manuscripts, and almost reversed Mewaldts dictum; many tracts of Galen are preserved in manuscripts of the twelfth, not the fifteenth century. The present study combines and continues these three approaches by concentrating upon one of the medical humanists, the Englishman John Caius, and upon his search for Galenic manuscripts in Italy and England in the middle decades of the sixteenth century. Caius himself published an account of his travels in De libris suis, but his reports of manuscripts in this work are often tantalisingly brief and of little value to a modern editor of the text. However, an examination of his copious marginalia, preserved at Cambridge and Eton, not only confirms his own reminiscences but also adds considerable new information in the form of notes, emendations and detailed collations of manuscripts that are either lost or, as yet, unidentified. Caius marginalia are impressive, not just for the immense quantity of codicological information they contain, but also for the quality of some of the readings and conjectures they report. In particular, the collations of the Codex Adelphi, whatever their source, offer significant new readings to future editors of Galen. The marginalia also help to resolve many puzzles in the printing and editorial history of Galen, as well as suggesting many new emendations, not all of them by John Caius. He himself was a competent critic, but, as his notes show, he was outclassed by John Clement and by Agostino Ricci. Finally, this study aims to bring to the attention of classicists some of the work being done on the hopes, motives and abilities of the medical humanists of the sixteenth century, and to suggest that, on this topic at least, historians of medicine and historians of the classical text can profitably learn from each other. Medicine in the sixteenth century was not confined to the improvement of anatomy, nor classical philology to literary texts.

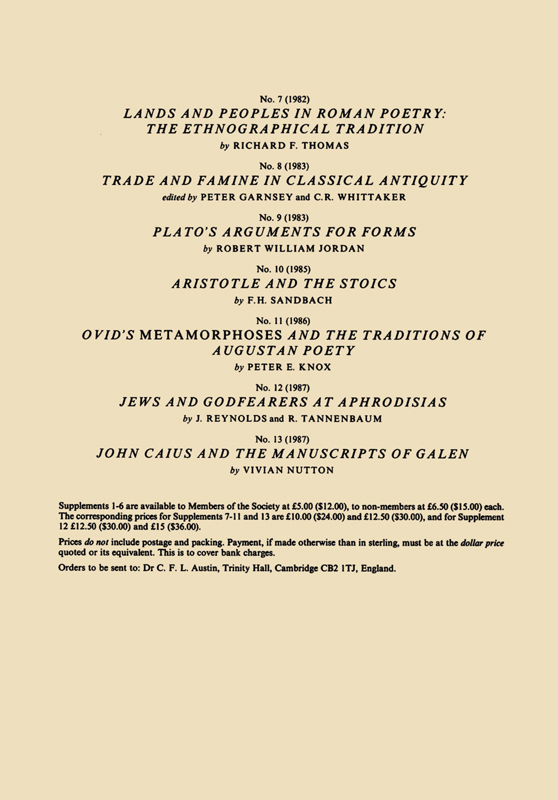

My list of acknowledgements is necessarily long. I am grateful for advice on matters codicological to Daniela Mugnai Carrara, Michael Lowry, Michael Reeve, and Nigel Wilson, and for assistance in checking manuscripts in European libraries and in locating rare publications by local historians to Daniel Bguin, Almuth Gelpke, Jacques Jouanna, and Jutta Kollesch. My Wellcome colleagues Faye Getz and Richard Palmer often joined me in puzzling over illegible squiggles and curious abbreviations, while Robin Price helped to smooth my path to Eton. Richard Durling, Joanne Phillips, and Andrew Wear read and commented on earlier drafts of this book, as did Charles Brink, Christopher Brooke, Philip Grierson and Jeremy Prynne. Their hospitality towards a non-Caian has been as much appreciated as their criticism, advice and encouragement. It was Charles Brink who first suggested the possibility of publishing this monograph as a Supplement to the Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society, and I am grateful to the Societys Editors for accepting it in that series, as well as to the Master and Fellows of Gonville and Caius College for financial help towards publication. Their Librarian, like his confreres at the Marsh Library, Dublin, the Leiden University Library, the John Rylands University Library, Manchester, Merton College, Oxford, the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, the University Library, Sheffield, and the Herzog-August-Bibliothek, Wolfenbttel, allowed me generous access to his books and manuscripts, and their staffs were ever courteous and helpful. Nor can I omit to thank the book-fetching staff of the Wellcome Library, for whom the daily delivery of Dr Nuttons Galen was a heavy task always cheerfully performed, and the team of secretaries who valiantly coped with a Topsy-like manuscript. Above all, I owe a double debt of gratitude to the Provost and Fellows of Eton and to their Librarian, Paul Quarrie; first for their financial help towards publication, and secondly for their willingness to let me keep the Eton Galen on extended loan at the Wellcome Institute for the duration of my researches. Without that rare privilege, this monograph would have been far longer in the making, and its authors patience with John Caius much reduced.

NOTES

. Recent publications of new texts from the Arabic include: Galen, On homoeomeries, Corpus Medicorum Graecorum, (CMG) Suppl. Or. 3 (1970); Rufus (?), Case-histories (1978); On jaundice (1983). Publication is expected soon of Galens Commentary on Airs, Waters and Places, On examining a physician, and On my own opinions