| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/lifeofrobertlord01malc |

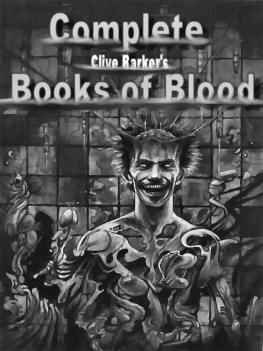

Engraved by Edwards, from a Painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

ROBERT LORD CLIVE.

London. Published by John Murray. 1836.

THE

LIFE

OF

ROBERT, LORD CLIVE:

COLLECTED FROM THE FAMILY PAPERS

COMMUNICATED BY

THE EARL OF POWIS.

BY

MAJOR-GENERAL

SIR JOHN MALCOLM, G.C.B. F.R.S. &c.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

WITH A PORTRAIT AND MAP.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET.

MDCCCXXXVI.

TO

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

THE EARL OF POWIS,

&c. &c. &c.

My Lord ,

This Life of your illustrious Father is dedicated

to your Lordship, in the conviction

that, had the Author been spared to complete

this, his last and favourite work, he

would have thus endeavoured to testify

his gratitude for your unvaried kindness,

and his affectionate esteem for your public

and private character.

I remain,

My Lord ,

Your Lordship's faithful Servant,

Charlotte Malcolm .

Warfield, April, 1836.

ADVERTISEMENT.

The present work was commenced in consequence of the possession of a body of unpublished documents, which, having been preserved among the family records at Walcot, were thrown open to the author by the friendship of the Earl of Powis. These consisted chiefly of the whole correspondence of Lord Clive, containing the originals of nearly every letter which he had received from the time when he first filled a public situation in India, down to the period at which he finally quitted that country; with copies of answers to many of the most important of them. They contained also several memoirs regarding the chief enterprises in which he was engaged, and minutes of council on the leading measures of his government.

From these sources, aided by the Reports of the different Parliamentary Committees, and other authentic materials, published and unpublished, Sir John had completed the introduction, and the first thirteen chapters, before he left India, in 1830. The fourteenth and fifteenth he finished after his return, and was engaged with the sixteenth, when death put a close to his labours.

The author was accustomed to bestow his final revision upon each successive portion of his work before he advanced to that which was to follow it. He had, consequently, made no preparation beyond the point where his progress was arrested; nor had he sketched out or indicated the plan he meant to pursue.

A gentleman for whose abilities Sir John Malcolm entertained a high respect, and by whose judgment it was his intention to have profited before he committed his work to the press, kindly offered to supply such a continuation as was necessary to bring down the narrative to the death of Lord Clive.

The materials which were here available were, of necessity, less abundant, less original, and less authentic than those from which the earlier part of the Memoirs had been composed.

After Lord Clive reached England, he filled no public situation, and had the means of settling his most important affairs directly by personal communication. The incidents of his English life were to be drawn chiefly from a limited and occasional correspondence with his more intimate friends, and the parliamentary proceedings from the reports in the periodical works of the day; in which the details of contemporary occurrences are infinitely less ample than are now afforded by similar publications.

The writer, therefore, by whose pen the concluding chapters were contributed, laboured under a difficulty which would have discouraged any person less influenced by friendship for the deceased, and by kindness for those on whom the publication devolved; but it has been surmounted in a manner which, it is hoped, will enable the reader to pursue the subject to its close, without any feeling of unsatisfied curiosity.

The family of Sir John Malcolm cannot close this brief notice, without expressing to the continuator of the work their warmest gratitude for the pains his affection has bestowed upon the last labours of his friend.

CONTENTS

OF

THE FIRST VOLUME.

INTRODUCTION.

General View of the State of India in 1746

Page

CHAPTER I.

Clive's Familyhis Boyhood.Events of his early Life in

India.History of the Carnatic to 1750

CHAP. II.

Wars in the Carnatic.Siege of Arcot, and subsequent

Operations of Clive till 1752

CHAP. III.

Clive returns to England, 1753.Again sent to India in

1755.Capture of Gheriah.Operations in Bengal.Calcutta

retaken, and Sujah-u-Dowlah forced to make

Peace

CHAP. IV.

Surrender of Chandernagore.Quarrel with Sujah-u-Dowlah

CHAP. V.

Conduct of Sujah-u-Dowlah.Intrigues at his Court.Battle

of Plassey.He is deposed, and Meer Jaffier raised

to the Musnud.Treaty

CHAP. VI.

Transactions subsequent to the Battle of Plassey

CHAP. VII.

State of Parties in Bengal, and in the Court of Meer Jaffier.Clive

proceeds to Patna.Accepts the Government

of Bengal

CHAP. VIII.

Clive projects an Expedition to occupy the northern Circars.Intrigues

at the Court of Moorshedabad.The

Shahzada's Invasion of Bahar.Repelled by Clivewho

receives a Jaghire

INTRODUCTION.

GENERAL VIEW OF THE STATE OF INDIA IN 1746.

Before entering on the Memoirs of Clive, it will be useful to take a succinct view of the state of India, at the period when he commenced his career in that country, and more especially of the coast of Coromandel, which was the scene on which he first displayed those talents that were afterwards to raise him to such eminence.

The emperors of Delhi, since the death of Aurungzebe ( A. D. 1707), had rapidly declined from the power they once possessed. The government of distant countries was intrusted to soubahdars (or viceroys), who invariably took advantage of the dissensions in the imperial family, or the weakness of a reigning prince, to endeavour to render themselves independent. The same motives and principles which governed the conduct of these vicegerents, actuated those whose allegiance and obedience they claimed in virtue of their delegated powers from the nominal Sovereign of India. Hindoo rajahs, and Mahomedan nabobs owned or rejected the sway of their superiors according to their means of resistance; while the Mahrattas, a name unknown to the military history of Asia before the middle of the seventeenth century, threatened, by a system of predatory warfare, to complete the destruction of these Mahomedan conquerors, whose chiefs, whether engaged in contest for the imperial Crown, the high office of soubahdar, or the inferior rank of nabob, appear to have lost, in their rancorous hostility to each other, all sense of union and of common danger, and to have blindly courted the aid of allies who (a little foresight would have shown them) were rising fast to greatness upon their ruin. These observations on the conduct of the Mahomedan princes are not more applicable to the connections they formed with the Mahrattas, than to those which, in the eighteenth century, they began to contract with Europeans. The Portuguese, who had discovered a passage to India in 1498, enjoyed the exclusive commerce with that country for a complete century; but their short and brilliant career was essentially different from that of the European nations who succeeded them. Their establishments were all maritime. They conquered and subdued the princes and chiefs on the shores and islands of India; but seldom, if ever, carried their arms into the interior, or engaged in any of those offensive and defensive alliances with native states, that must have hurried them into contests, to support which the resources and strength of the mother country would have been altogether inadequate. In consequence of this policy, their established character for valour, and the strength of their fortifications, they did not become objects of attack to the principal native powers of India. Neither the Emperors of Delhi, nor their princely delegates had, or desired to have, any naval force. They attached no value to the sea-coast or to islands, but as they might produce them profit through the medium of customs: and the increased commerce, consequent to the settlement of the Portuguese at Goa and other parts, was calculated to reconcile them to a nation, whose warfare on the continent of India was almost entirely limited to contest with the petty princes and chiefs who occupied or claimed the shores where they desired to settle.