Contents

Guide

Page List

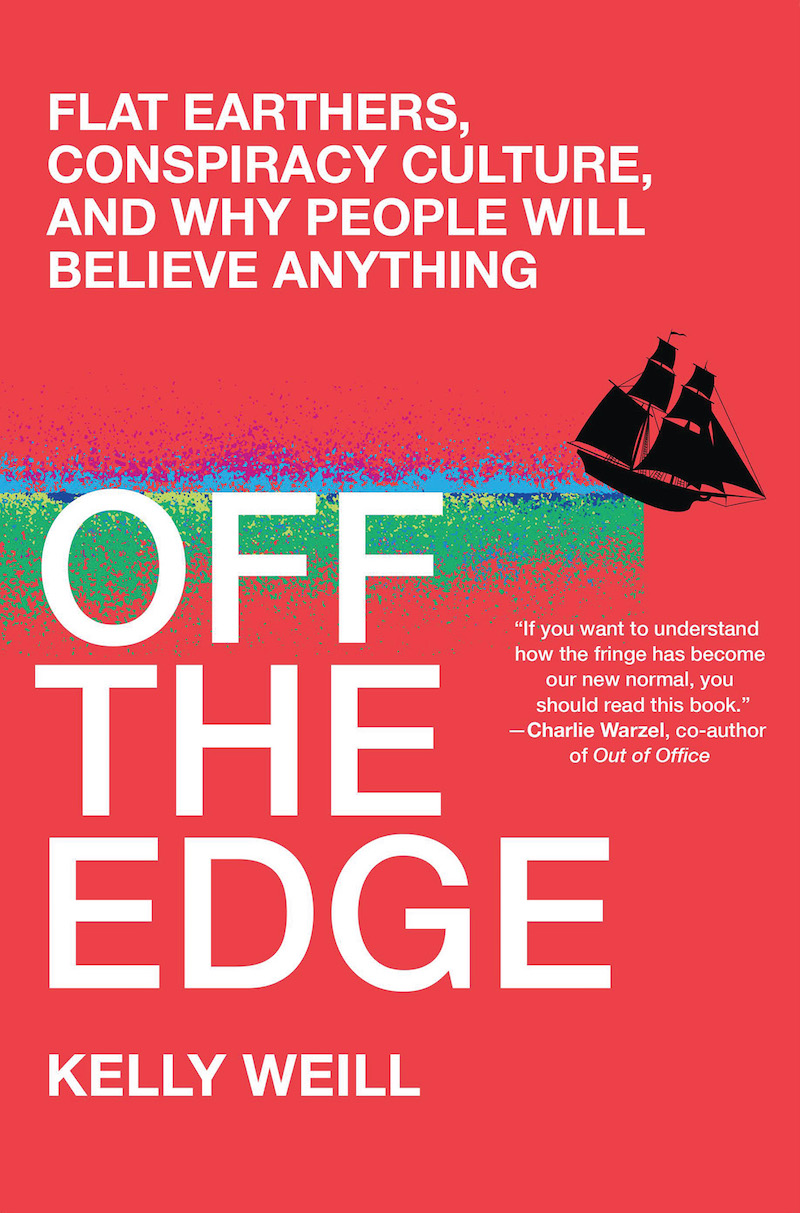

Off the Edge

Flat Earthers, Conspiracy Culture, and Why People Will Believe Anything

Kelly Weill

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2022

To J. and C., who were with me the whole way.

contents

Off the Edge

Prologue

The summer before he fell from the sky, Mike Hughes was experimenting with amateur jet propulsion. It was going badly.

Problem again today, he texted me in August 2019.

With the rocket, or weather? I asked.

Rocket.

This was his second failure in two days, and Id lost count of the times hed run into trouble with wind or parachutes or spare rocket parts hed purchased off Craigslist for $325. Most people would have given up years earlier, maybe taken up a less lethal hobby. I certainly thought hed quit.

Hes gotta know, right? I remember asking my husband. I was standing in our kitchen, texting Hughes with one hand and brandishing a spatula with the other, making an omelet while trying to talk Hughes out of launching himself into low orbit. Deep down, hes gotta know Earth is round. Thats why he keeps having these rocket failures. Earth is round, and he doesnt want to prove it.

I liked Mike. He was an offbeat guy, but a good one. Wed met the previous year at a conference for people who believe the earth is flat. I was there as a journalist for the Daily Beast, the news website where I reported on extremist movements and conspiracy theories. He was there to drum up support for a self-manned rocket launch into the upper atmosphere, during which he would decide the planets shape for himself. He and I sat around talking trash and the particulars of rocket science. Throughout the next year, hed send me updates: pictures of rocket designs, gossip from the conspiracy scene, and invitations to more conspiracy conventions. This wasnt a guy with a death wish. This was a man whod lived six bombastic decades and had no intention of stopping. So when he texted me about a summers worth of rocket troubles, I thought it was his good sense finally rebelling against a bad idea. After all, who truly thought Earth was flat?

But Mad Mike Hughes was a believerin thrifted rocket parts, in back-of-the-envelope flight calculus, in himself, and most famously, in Flat Earth.

Flat Earth theory, the idea for which Hughes was willing to shoot himself into the stratosphere, represents a profound misunderstanding of the world. But the theory and those who believe it are also misunderstood, by the world at large. Ive spent years hobnobbing with Flat Earthers at conferences across the United States and interviewing them on the weekends, becoming the friend of some and the enemy of others. Some have called me for legal advice, and others have labeled me a saboteur out to sink the movement. Ally or archnemesis of Flat Earthers, Ive spent enough time among them to sympathize with them on one key grievance: nearly every common assumption about Flat Earth is wrong. Maybe you learned as a kid that people expected Christopher Columbus to sail off the edge of a flat planet. Or maybe youve seen people refer to Flat Earth an example of a backwards-thinking ideology held in Europes Middle Ages. The truth is that, by at least the fifth century BCE, Greek astronomers and mathematicians had already determined that the earth was round and had popularized the formulas that proved their calculations. By Columbuss day, the globe model had been the default for centuries. (In fact, we can credit the Columbus Flat Earth myth to Rip Van Winkle author Washington Irving, who seems to have more or less invented it in his heavily embellished Columbus biography in the 1820s.) Flat Earth theory is a new idea, one that emerged in a utopian commune in England decades after Irvings account of Columbus. It simmered in hard-core religious communities in the United States in the early 1900s, found a home with moon-landing skeptics in the back half of the twentieth century, and skyrocketed to popularity in the late 2010s, the same time Mike Hughes was teaching himself rocket science.

Hughes was a walking reminder of the other mistake people make about the movement: that Flat Earthers are wackos, denizens of societys fringes. But Flat Earthers exist among usoften so inconspicuously that youd never notice unless you asked. Some are parents, some are self-taught aerospace engineers, and some are professional athletes. Some are clever, some are kind, some are neither, and at least two have released bad rap songs that praise both Flat Earth and Adolf Hitler. On the whole, however, Flat Earthers comprise a spectrum of people who are seldom much different, or any dumber, than the rest of us.

Their theory typically claims Earth is as flat as a Frisbee, surrounded by ice at its perimeter, and maybe enclosed by a great, impenetrable dome. The details vary from believer to believer. Most Flat Earthers (but not all) do not believe in outer space. Though many are dismissive of gravity as a concept, some claim that the planet is constantly accelerating upward, while others disagree and claim that the only reason we dont drift off the ground like escaped party balloons is because humans are heavier than air. But unless you find yourself in an argument over the theorys nuances at a Flat Earth conference, they are of secondary importance. Flat Earth is best understood not as a viable science with meaningful specifics but as the ultimate incarnation of conspiratorial thinking. Members of the movement believe governments and scientists are actively peddling a globe lie in order to control the world by tarnishing religious teachings or by making people feel insignificant next to the great expanse of outer space. For the past 150-odd years, this bizarre theory has grown by borrowing age-old mistrusts and exploiting new forms of communication, from newspapers to radio toeventually, explosivelythe internet.

Todays world looks different than it did when I began work on this book, and not just because Ive spent that time among people who believe the earth is flat. Widespread civil unrest, a contentious presidential election, and the outbreak of a catastrophic pandemic have seeded the United States with so much suspicion that I need to clarify, up front, how I use the term conspiracy theory. Jan-Willem van Prooijen, a psychologist specializing in conspiracy theories, lays out five criteria that qualify a belief as a conspiracy theory: the theory must explain correlations between events and actors; the perpetrators must have acted deliberately; multiple people must have been involved in the plot; the plot must be ominous in its deception (and not a benevolent cover-up, like concealing a surprise birthday party); and the cover-up must be ongoing. Conspiracy theory, for the purposes of this book, refers to an unproven allegation of a secret, deliberate, and malevolent plot, like a scheme to conceal the true shape of the world. Conspiracies theories are ways to construct order and meaning in times of uncertainty. They let us shape our fears into something we understand.

Belief in conspiracy theories is highly common. Study after study, across multiple continents, has found that more than half of respondents support some conspiracy theory or another. Some of those theories turn out to be true. The United States has been involved in damning and demonstrably true plots on its own soil (like the FBIs plot to discredit Martin Luther King Jr.) and abroad (like the Reagan administrations plot to illegally sell weapons to Iran in order to support counterrevolutionaries in Nicaragua). In light of these revelations, suspicion might seem justifiable, even reasonable, to many Americans. Im no exception here. For instance, I am militant in my unproven belief that Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh was aided by sympathetic, uncharged members of the white power movement. Given an hour and a strong drink, I will talk your ear off about this, possibly while drawing maps and diagrams on the nearest surface. My belief probably means I can be classified as a conspiracy theorist.