CASS LIBRARY OF AFRICAN STUDIES

Missionary Researches and Travels

No. 21

General Editor : ROBERT I. ROTBERG

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

MISSIONARY TO TANGANYIKA

1877-1888

First published in 1971 by

FRANK CASS AND COMPANY LIMITED

67, Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3BT

Distributed in the United States by

International Scholarly Book Services, Inc.

Beaverton, Oregon 97005

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 72-171259

ISBN 13: 978-0-714-62605-5

ISBN 10: 0-714-62605-8

Introduction Copyright 1970 James B. Wolf

Printed in the Republic of Ireland by Cahill & Co. Limited,

Parkgate Printing Works, Dublin

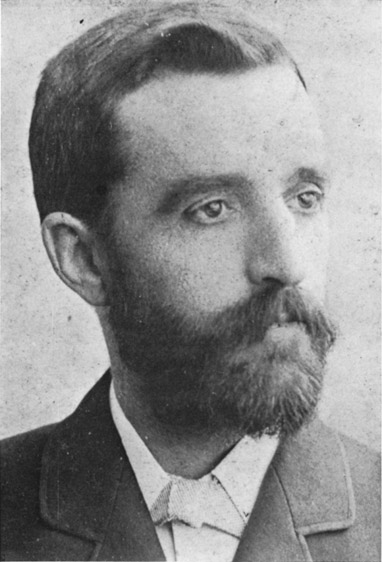

Illustrations

E DWARD C OODE H ORE

General Editors Preface

Anyone who has done research on the problems of nineteenth-century eastern Africa knows how uncommonly often the name of Edward Coode Hore, master mariner and missionary, appears. He was a forceful representative of evangelical initiative at Lake Tanganyikaa friend and counsellor of explorers, adventurers, imperialists, and African and Arab merchants, and the fulcrum of the pioneering London Missionary Society from 1878 to 1888. For a time he was the Wests chief representative in a critical region of the interior, and one well-placed to affect the course of Euro-African relations on the eve and during the so-called scramble.

Hore was a more complicated and influential man than he often appears. Among missionaries, too, his sensibility stands out. A biography is long overdue and, in time, Professor James Wolf of the University of Colorado hopefully will produce it. Hore himself published Tanganyika (London, 1892) and his wife published the strikingly titled To Lake Tanganyika in a Bath Chair (London, 1886). But neither account bears reissuance in full. The second is a slight, if humorous period piece. The first, ostensibly a likely candidate for inclusion in this series, lacks lasting interest and is unrepresentative of the quality of the man and his work. When Professor Wolf, whose dissertation was a study of Hores mission, and I discussed this problem some years ago we soon realised that Hores best material was buried elsewherein an unpublished journal to which Professor Wolf had accesss and in his published articles. For this volume Professor Wolf has therefore edited a collection of the less well known but more substantial parts of the Hore oeuvre . The authentic nineteenth-century practical man of God emerges in context.

R.I.R

1 April 1970

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Acknowledgements

The editor wishes to thank the directors of the Congregational Council for World Mission, formerly the London Missionary Society, for permission to publish the journals of Edward Coode Hore, and to extend particular personal appreciation to Miss Irene Fletcher for her help and co-operation in 1967. The Department of History, University of California at Davis, and a grant from the Council for Research and Creative Work at the University of Colorado, helped to finance the costs for this collection. The editor is responsible for all material contained in the footnotes.

J.B.W.

1971

I

Introduction

Edward Coode Hore, a sailor with ten years experience in the merchant navy, was one of two artisans appointed in 1877 to the pioneering expedition of the London Missionary Society (LMS) to Central Africa. His duties, once the caravan had reached its destination, were to complete the geographic survey of Lake Tanganyika begun by Richard Burton and augmented by Verney Lovett Cameron and Henry M. Stanley, ferry missionaries and supplies to the various parts of the lake where stations would in time be established, and receive, assemble, and command a steamship to be transported piecemeal overland to the lake. If it were not for the need to service an indeterminate number of lakeside mission stations by steamer, the foreign secretary of the society would not have been so anxious to employ a sailor skilled in handling steamships as well as sail, nor would have Hore been so pleased to accept, for it was exclusively as the master of a ship that he desired to give expression to his religious dedication.

Perhaps the major factor behind the flurry of missionary fervour in Great Britain, which so affected Central Africa in the 1870s, was David Livingstones death at Lake Bangweulu and public burial in Westminister Abbey and the publication in 1874 of his last, dramatic journals. When Livingstone had requested help in 1857, few had followed him back into the interior of east Africa, but his death sparked Scottish and English missionary societies to abandon their previous hesitation, alter their priorities, and plunge enthusiastically into Central Africa. No doubt their decisions were favourably affected by the logistical changes brought about by the opening of the Suez Canal; no doubt their directors were heartened by the increasing British influence with the Sultan of Zanzibar who implied suzerainty over the Muslim traders and settlers in the interior. But it was primarily as a memorial to Livingstone that two Scottish societies undertook activities in the Lake Nyasa region; it was the search for Livingstone which first had brought Stanley to Africa, and it was on his recommendation and virtual guarantee of success that the Church Missionary Society obligated itself to the establishment of a mission in Buganda at the north end of Victoria Nyanza.

The Sea of Ujiji (Lake Tanganyika), probably in Europe the best known of the great inland lakes, remained beyond the missionary assault until the end of 1875. Then Robert Arthington, a rather eccentric Quaker from Leeds who was dedicated to no less an effort than the early evangelisation of the world, noticed the gap and, using his capital as an enticement, requested the London Missionary Society to fill it. If, he suggested, Livingstones former society agreed to establish a station at Ujiji, a town so popularly linked with Livingstones name, and if that mission included a steamship, a means for inland transport in which Livingstone had great faith, then he would contribute an initial 5,000 to the endeavour. The financial lure worked, and, while it took another twelve years to get The Good News steaming under her own power on Lake Tanganyika, her promised arrival was the reason that Hore was among the first three missionaries to arrive at Ujiji in August, 1878.

For the next decade the Central Africa Mission was dominated by the endurance, determination, and self-assurance of this sailor missionary. Reinforcements and replacements, often disagreeing and sometimes overruling Hore as to the direction and focus of the mission, did not survive the rigors of the tropics; if they lived, they were invalided home in failing health and flagging spirit. But Hore stayed on, dispatching home optimistic reports, which suggested that all that was needed for success was better quality missionaries : I would say you ought to send a lot of old sailors out here.

While the London Missionary Society stations were the only British outposts at Lake Tanganyika, two other European agencies were present during the 1880s: the Association Internationale Africaine, sponsored by King Lopold II of Belgium and the Roman Catholic Socit de Notre-Dame dAfrique (the White Fathers) based in Algiers. With Hore at its helm, the LMS mission seemed to have more in common with the secular representatives of the former than with the White Fathers.