First published in 1963 by Oxford University Press for the International African Institute.

This edition first published in 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1963 International African Institute

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-8153-8713-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-429-48813-9 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-58961-2 (Volume 34) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-49153-5 (Volume 34) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

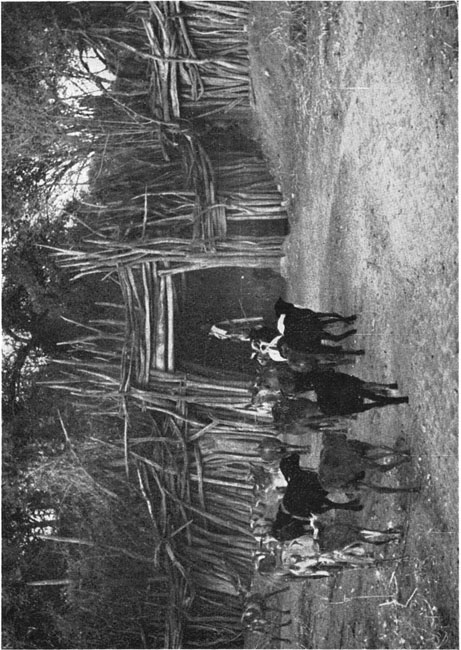

Gateway of a Sonjo village

The Sonjo of Tanganyika

AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY OF AN

IRRIGATION-BASED SOCIETY

ROBERT F. GRAY

Published for the

INTERNATIONAL AFRICAN INSTITUTE

by the

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO

1963

To My Mother

and the Memory of My Father

CONTENTS

Oxford University Press, Amen House, London E.C.4

GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI LAHORE DACCA CAPE TOWN SALISBURY NAIROBI IBADAN ACCRA KUALA LUMPUR HONG KONG

International African Institute 1963

Printed in Great Britain

This book is based upon field work which was carried out during the last six months of 1955. The meagre information about the Sonjo which I possessed prior to this visit indicated that they were a distinctive, closely knit society practising irrigation. I planned my research with the limited object of investigating the irrigation system and its relation to the social structure, hoping thereby to obtain insight into a type of ecology and social system which has not previously been studied in sub-Saharan Africa. In the present book I submit my findings and interpretations.

The period of my field research coincided with the dry season, during which the motor road to Sonjo is open. It was also the period during which the irrigation system was in full operation. I was fortunate in being able to witness the two important annual festivals of the Sonjo. Although the harvest festival was only celebrated at one village during my stay, the second festival took place at all the villages. Much of my information about Sonjo religion comes from observations and conversations at these festivals.

The Sonjo are quite definitely xenophobic in their attitude towards the outside world; some of the reasons for this will appear in the text of the book. In the past, the Sonjo villages have been virtually closed to outsiders, except for government officials, unless accompanied by an approved escort. My wife and I were not allowed to locate our camp inside any of the villages, and in the early weeks of research my movements in the villages were somewhat restricted and constantly observed. Later on, the suspicion with which I was first regarded decreased considerably. It was a great advantage during my first month to have as guide and informant Simon Ndula, the author of the mythological text, published by Fosbrooke (1955), which is discussed in chapter VII He was a native Sonjo, seconded from his duties as government messenger and assigned to me by the District Commissioner of Masai District.

Our field camp was located near the villages of Kheri and Ebweabout a quarter of a mile from either villageand most of my observations were made at those two villages. The headman of Ebwe was unusually helpful. It was only through his sympathetic support that I was enabled to complete a house-to-house survey of an entire ward of that village. As regular informants I employed two very able young men, one from Kheri and the other from Soyetu. I made regular visits to Soyetu, spending about one day a week at that village. Most of my data were confirmed by informants from Kheri, Soyetu, and Ebwe. For the other three villages (there are six in all) my data are incomplete. Therefore, the statements in the text can be taken to apply to three of the villages except where I indicate otherwise. I am quite satisfied, however, that the same basic institutions are present in all the Sonjo villages.

As there were no English-speakers among the Sonjo, I used Swahili as a medium of communication. This language is known by nearly all the younger adult men of the tribe and by a fair number of older men. It is becoming the custom for men of the warrior class to spend from two to four years in other parts of Tanganyika or Kenya working as migrant labourers or livestock traders, and there they learn Swahilithe lingua franca of East Africa. In the later stages of my work I supplemented Swahili with a basic vocabulary of Sonjo words. My informants acted as interpreters when I interviewed some of the old men who knew no Swahili. My wife became acquainted with three Sonjo women who had learned Swahili during prolonged residences with their husbands at Loliondo. From them she was able to obtain some information which was otherwise inaccessible to me. In the book I indicate the native names for various items of technical equipment. This is more for the sake of the ethnographic record than for any value it has in my analysis. Otherwise vernacular words are kept to a minimum and are used only when I think that English equivalents do not adequately express an idea, or in some cases to emphasize that an idea is embodied in a special word. Every Sonjo word is identified or defined when first used.

No general anthropological study of the Sonjo had been made prior to my field research. A number of writings which deal in one way or another with the Sonjo are mentioned in the book. In addition to these, two articles not cited in the text which provide some background material are a short account of the defensive measures of the Sonjo by Fosbrooke (1955a) and some notes on Sonjo land tenure by Griffiths (1940). In the chapters that follow I shall be presenting for the most part data collected by myself in the field.