The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1980 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 1980

Paperback edition 1985

Printed in the United States of America

13 12 11 10 11 12 13 14

ISBN 978-0-226-19146-1 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

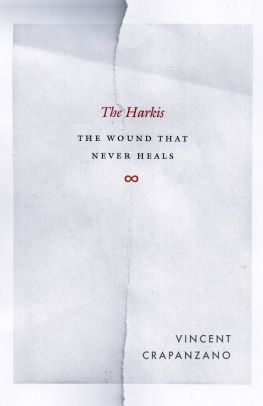

Crapanzano, Vincent, 1939

Tuhami, portrait of a Moroccan.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. EthnologyMorocco. 2. Tuhami. 3. EthnologyFieldwork. 4. MoroccoSocial life and customs. 5. MoroccoBiography. 6. Psychoanalysis. I. Title.

GN649.M65C7 301.29'64 79-24550

ISBN 0-226-11871-1 (paper)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Preface

Tuhami is an experiment. Whether it is a successful one or not I cannot say. Ever since my first experience of field workit was with Haitians in New York City, for a course in anthropological field methods with Margaret MeadI have been deeply concerned with the anthropologists impress on the material he collects and his presentation of it. Anthropologists have been inclined to proclaim neutrality and even invisibility in their field work; certainly they have tended to efface themselves in their descriptive ethnographies. I have come to believe that in doing so they have acted in what Jean-Paul Sartre (1956) would call bad faith and have presented an inaccurate picture of ethnography and what it can reveal. I do not mean to imply insincerity or prevarication on the part of the individual anthropologist; I want only to call attention to a culturally constituted bias, a scotoma or blind spot, within the anthropological gaze.

By eliminating himself from the ethnographic encounter, the anthropologist can deny the essential dynamics of the encounter and end up producing a static picture of the people he has studied and their ways. It is this picture, frozen within the ethnographic text, that becomes the culture of the people. The ethnographic encounter, like any encounter between individuals or, for that matter, with oneself in moments of self-reflection, is always a complex negotiation in which the parties to the encounter acquiesce to a certain reality. This reality belongs (if it is in fact possible to speak of the possession of a reality removed from any particular social or endopsychic encounter) to none of the parties to the encounter. It isand this is most importantusually presumed to be the reality of ones counterpart to which one has acquiesced, to expedite the matter on hand. This presumption, which is rarely articulated as such in most ongoing social transactions, gives one the comforting illusion of knowing ones counterpart and his reality. Expressed within a pragmatic mode (to expedite the matter on hand), it permits a certain disengagement from the reality of the transaction. The disengagement helps to insulate the parties to the encounter from the repercussions of failure. It permits, too, a superior stance in the inevitable jockeying for power that occurs within such negotiations.

In the ethnographic encounter, where the matter at hand is the knowledge of the Other and his reality, there is a very strong compulsion to attribute the negotiated reality to ones informant. There are, to be sure, all sorts of analytic strategies that have been devised to distinguish between what is specific to an encounter and what is typical, general, or even universal. Such strategies, which include multiple and repetitive questioning in different contexts, the use of several modes of elicitation, the search for pattern, consistency, and redundancy, confirmation in the research of others, the evaluation of informants, and, ultimately, self-reflection and evaluation, must be regarded with a certain skepticism, for they mayand often doserve as rationalizations for the objectification of the negotiated reality and its attribution to the Other. They frequently presuppose a degree of lucidity that is impossible for any participant within the encounter. The anthropologist has no more privileged access to lucidity than did the impassioned heroes of Racinian tragedy.

I am not making a plea for subjective anthropology. I do not wish to deny the anthropological enterprise, as some critics have tried to do (Hymes 1974), or to proclaim a new anthropology. I wish rather to call attention to an essential feature of the ethnographic encounter and its effect upon the anthropologists productions. I believe that such a critical understanding is necessary for a realistic evaluation of the anthropological endeavor and the ethical and political role of its practitionersa role that is so often masked behind one ideology or another. (I am aware of the fact that my argument, too, is the product of an ideology, which, from within, I would characterize as self-reflective, involuted, inevitably circular, ironic, and not without a certain iconoclasm.) My point here is that, as anthropologists, we have a responsibility to the people we study, if not to our readers, to recognize the ethical and political implications of our discipline. Every interpretive strategy, including those implicit within description itself, involves choice and falls, thereby, into the domain of ethics and politics.

Tuhami is a complicated work. It is a life history of a Moroccan tilemaker who was married to a she-demon, a jinniyya, named Aisha Qandisha. It is also an attempt to make sense of what Tuhami the tilemaker related to me the anthropologist and to come to some understanding of how he articulated his world and situated himself within it. It raises the question of his freedom and the constraints, both within him and without, on that freedom. Above alland I write with uneasiness and a certain regretTuhami both as text and as a fellow human being enables me to raise the problematic of the life history and the ethnographic encounter. Tuhami becomes, thereby, a figure within an imposed allegory that in a very real sense bypasses him. My own obtrusive presence in his life not only enables Tuhami to tell his story; it also permits me the luxury of entering that allegory in the name of a science that is unknown to him. Through that science, through anthropology, my position with respect to Tuhami is rationalized. Knowingly, I have made that choice.

Much has been written in recent years about the role of symbols in social and ritual life, but little has been written about the role such symbols play in the individuals life or its articulation. Anthropologists like Clifford Geertz, Victor Turner, and, above all, Nancy Munn have all suggested that cultural and ritual symbols affect the way in which the individual experiences his world; but they have not, to my knowledge, looked in detail to the individual to substantiate their suggestions. There is, of course, no way that we can know, except perhaps through an empathetic leap, how the symbols are appreciated within the conscious life of another individual. We

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.