Acknowledgments

This book is the outcome of years of help and hospitality from the young women and men of Point Place. My gratitude is immense. Ngiyabonga, abangani bami.

To those not from Point Place but who were an important part of my fieldwork experiences in Durban, tooKeith Breckenridge, Catherine Burns, Jeff Guy, Meghan Healy-Clancy, Jason Hickel, Helmut Holst, Mark Hunter, Lesley Lewis, Andy MacDonald, Gerhard Mar, Sarah Mathis, Julie Parle, Rene Reynolds, Ilana van Wyk, and Thembisa Waetjena big thank you for your friendship, conversations, and housing! At the University of KwaZulu-Natal, my instructors in isiZulu, Mary Gordon, Msawakhe Hlengwa, Zoliswa Mali, Nelson Ntshangase, and Mpume Zondi, made language learning a pleasure and a possibility. And this includes Sandra Sanneh as well! To the organizers and participants of the History and African Studies Seminar, I am grateful for your comments and suggestions, which shaped the early drafts of this book. And to the Social Anthropology Department, thank you for the institutional affiliation. Similarly, as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand, I benefited immeasurably from the institutional support of the university and from the intellectual insights of my colleagues. To the Social Anthropology Department, David Coplan, Kelly Gillespie, Gavin Steingo, Carol Taylor, Robert Thornton, and Shahid Vawda, I learned much from your dedication to your students. Now that I am a full-time teacher, I recognize the immensity of your hard work!

This research also was made possible by the generous support of several granting agencies, which included a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Grant, a National Science Foundation Cultural Anthropology Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant, a fellowship from the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, and an Andrew Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship. In addition, I wish to acknowledge the institutional support of Yale University, which provided fellowships not only for my studies in graduate school but also for preliminary fieldwork investigations and language training in South Africa, which included a Foreign Language Area Studies Fellowship.

To the members of Yale's Department of Anthropology (who now are so far afield!), my acknowledgments are many. Foremost to Eric Worby, whose intellectual guidance and mentoring have been invaluable to me. To Kamari Clarke and Mike McGovern, I am deeply grateful for your support. To Isak Niehaus, who, in his visiting year, inspired me with his enthusiasm for South Africa and has been generous with his friendship ever since. To my friends, mentors, and writing and traveling companions: Allison Alexy, Devika Bordia, Seth Curley, Judd Devermont, Joseph Hill, Jennifer Jackson, Libby Jones, Juan Orrantia, Richard Payne, Mieka Ritsema, and Gavin Whitelaw, thank you for the laughter and listening ears. And, to Kay Mansfield, it was an honor to be a Marvelette!

More recently, at Ripon College, I have benefited from the warm welcome of the Anthropology Department. Thank you, Paul Axelrod, Emily Stovel, and Bill Whitehead. To the Ceresco Research Workshop in the Humanities and Human Sciences, it was a pleasure to present the final drafts of this book. And, of course, to my students, who have helped me remember what makes reading ethnography so much fun. Here I also wish to acknowledge my gratitude to the two, as it turns out, not-so-anonymous reviewers of this book, Adam Ashforth and Mark Hunter. I am indebted to you for your comments, suggestions, and insights, and, as the following pages reveal, for your scholarship. Here, too, a special thanks to Norm Whitten and Danny Nassett, editors at the University of Illinois Press. I never imagined that walking past a book booth at a conference would lead to such productivity! And to Jane Lyle, thank you for your keen eye and insightful edits to this manuscript.

Over the years, portions of this book have benefited from the comments and suggestions of anonymous reviewers. Sections of the introduction and appeared as an essay, Parting Homes in KwaZulu-Natal, in Ekhaya: The Politics of Home in KwaZulu-Natal, edited by Meghan Healy-Clancy and Jason Hickel (Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2014), 190314, and is reprinted with permission from the University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge the love and support of Michael Mahoney, whose enthusiasm for South Africa has meant the world to me. And, to my family, who have helped me through it all. Thank you for everything.

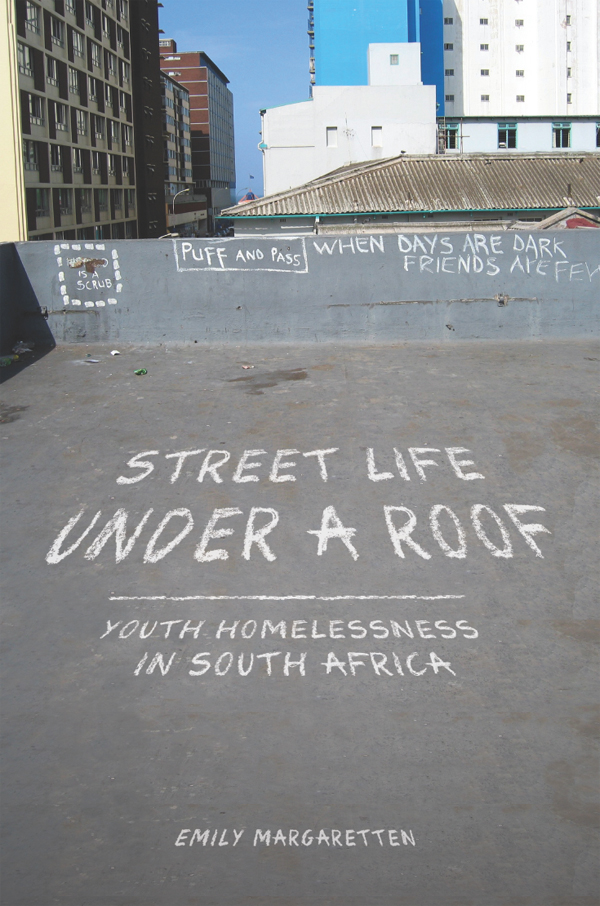

Introduction

Vignette One: Vigilante Justice and Street Rehabilitation

Did you hear what happened to me over the weekend? A group of young men and women are relaxing in a shaded park on a Sunday afternoon. It is the end of summer in Durban, a South African city known for its subtropical climate and expansive beaches along the Indian Ocean. I am sitting near the group and overhear the story. The young woman explains to her companions that a teenage boy stole her purse while she was sunbathing on the beach. The purse contained the wallets, cell phones, and car keys of her friends, too. A few seconds after the theft, the woman realized what had happened and jumped up from her towel. She saw the teenager with her purse and shouted for help. A mob set upon the boy, who fell to the ground, trying to protect himself from the blows to his body and head.

Ay, it was vigilante justice, a young man remarks.

They were angry, the woman answers. They hurt him badly. She goes on to say that they brought the teenager to the police station. She decided not to press charges, though, for he already had suffered enough from the beating. The police also said that there was not much else they could do, for the boy had returned the purse to her with all the contents in it. As a final warning, they planned to drive him far out to the bush, where it would take him several days to walk back to the city, possibly longer because of his injuries.

They do that for those big conferences, another girl muses. She is referring to a practice in which police officers round up street kids from the beachfront and dump them in remote places when there is an influx of visiting foreigners and dignitaries to the city. The group is quiet, contemplating her statement as well as the mob beating of the teenage boy.

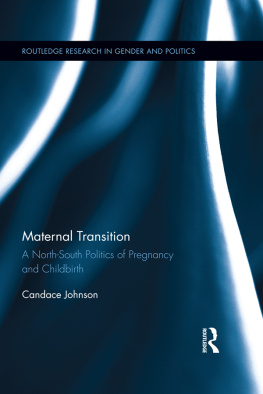

Figure 1. The South African provinces. Durban is located in the province of KwaZulu-Natal along the Indian Ocean.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.