CHAPTER I

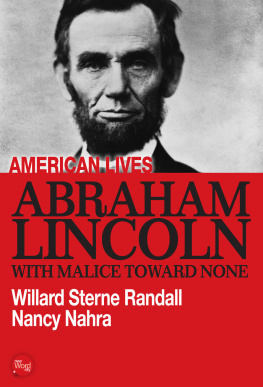

The Fourteenth of April

THE fourteenth of April 1865, dawning on the city of Washington, found the Capital gaudily bedecked with flags; for on the preceding night, Lees surrender had been celebrated by a grand illumination. The end of the long war was at last in sight.

In the forenoon a regular meeting of the Cabinet was held, at which General Grant was present as a distinguished guest. The victor of Appomattox Court House was a medium-sized, stoop-shouldered, taciturn man, then at the zenith of his military glory. At the White House he met all the members of Lincolns official family, except Secretary of State Seward, who had been the Presidents closest rival at the Chicago Republican convention of 1860. Seward had been thrown from his carriage a few days before and was lying at home under the care of physicians. The framework of steel which encased his face and neck, agonizing though it must have been, was destined that night to save his life.

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles was there; a kindly-looking man with a long white beard, who was gifted with a shrewd insight into the character of men. Thoroughly loyal to his Chief, and with a finely balanced judgment, he kept close watch on the events of his era and faithfully recorded them in his diary.

The President himself seemed in unusually good spirits. Before the opening of the formal meeting he spoke freely of his plans for reconciling the conquered South. So far as he was concerned, he promised, there would be no persecution; he even hoped that the fallen leaders of the Confederacy would leave the country and thereby make it unnecessary for him to take direct action against them. He then told of a dream that had come to him during the night, the same that had so often in the past presaged a portentous happening. This time he hoped that it foretold the surrender to General Sherman of the last Confederate army. As Lincoln was describing his dream, Stanton entered. The President stopped abruptly. Gentlemen, he said, let us proceed to business.

Stanton did not often attend Cabinet meetings and, when he came, he usually came late. It was his way of indicating the superiority he felt over his colleagues, if not over Lincoln himself. Gideon Welles distrusted him intensely, considering him an unscrupulous intriguer. He has cunning and skill, the head of the Navy Department once wrote in his diary, dissembles his feelings... is a hypocrite....

With Stantons entrance the pleasant flow of informal conversation ceased. The Secretary of War had brought with him an outline of the first step that he thought should be taken along the road to reconstruction. He contemplated the creation of a military territory combining Virginia and North Carolina, and the placing of this district under the supervision of his own department. Welles immediately offered objections. He declared that state lines should be inviolate and that the plan submitted would aggravate, rather than harmonize, the feelings of the two hostile sections. Lincoln sided with Welles, but tactfully suggested that Stanton should furnish a copy of his scheme, for study and future discussion, to all the Cabinet officials. Soon afterward the meeting adjourned.

On the same day, early in the morning, a shambling little man, whose head seemed wedged between his shoulders, rented a room at the Kirkwood House on the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and Twelfth Street. With an unpracticed hand he wrote his name on the register: G. A. Atzerodt.

In the afternoon, a handsome young actor walked into the lobby of the same hotel and asked for Vice President Andrew Johnson. When informed that he was not in his apartment, the visitor left with the clerk a card on which he had scribbled these words:

Dont wish to disturb you Are you at home?

J Wilkes Booth

The young man then left and mingled with the crowds on the avenue.

Had anyone been able at that time to read the significance of these two incidents, he would have recognized in them the shadow which all great events are said to cast before them; for they were the only outward evidence of a conspiracy that was then afoot against the life of the President.

That evening John Wilkes Booth shot Abraham Lincoln during a performance at Fords Theater.

Clara E. Laughlin, The Death of Lincoln, (Doubleday Page, New York, 1909), pp. 71, 72 (footnote)

Gideon Welles, Diary (Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, 1911), II, pp. 16, 58; I, p. 127

Ibid., I, p. 67

Ibid., II, pp. 28182

Benn Pitman, The Assassination of President Lincoln, (Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin, Cincinnati, 1865), p. 144

Pitman, op. cit., p. 70; quoted from original card, War Department Archives, Washington

CHAPTER II

Assassination

THE story of Lincolns assassination has never been more concisely told than through the official telegrams in which Secretary of War Stanton informed the world of that tragedy. These messages, in conformity with a rule established earlier in the war, were sent to General John A. Dix in New York, from whose headquarters they were given to the press for wider dissemination.

Here are the dispatches of that memorable night:

(No. 1) | WAR DEPARTMENT

April 15, 18651:30 A.M.

(Sent 2:15 A.M.) |

Major-General DIX,

New York:

Last evening, about 10:30 P.M., at Fords Theater, the President, while sitting in his private box with Mrs. Lincoln, Miss Harris, and Major Rathbone, was shot by an assassin, who suddenly entered the box and approached behind the President. The assassin then leaped upon the stage, brandishing a large dagger or knife, and made his escape in the rear of the theater. The pistol-ball entered the back of the Presidents head, and penetrated nearly through the head. The wound is mortal. The President has been insensible ever since it was inflicted, and is now dying.

About the same hour an assassin (whether the same or another) entered Mr. Sewards home, and, under pretense of having a prescription, was shown to the Secretarys sick chamber. The Secretary was in bed, a nurse and Miss Seward with him. The assassin immediately rushed to the bed, inflicted two or three stabs on the throat and two on the face. It is hoped the wounds may not be mortal; my apprehension is that they will places, besides a severe cut upon the head. The attendant is still alive but hopeless. Major Sewards wounds are not dangerous.

It is now ascertained with reasonable certainty that two assassins were engaged in the horrible crime, Wilkes Booth being the one that shot the President, the other a companion of his whose name is not known, but whose description is so clear that he can hardly escape. It appears from a letter found in Booths trunk that the murder was planned before the 4th of March, but fell through then because the accomplice backed out until Richmond could be heard from.