Copyright 1980 by Ivan Doig

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

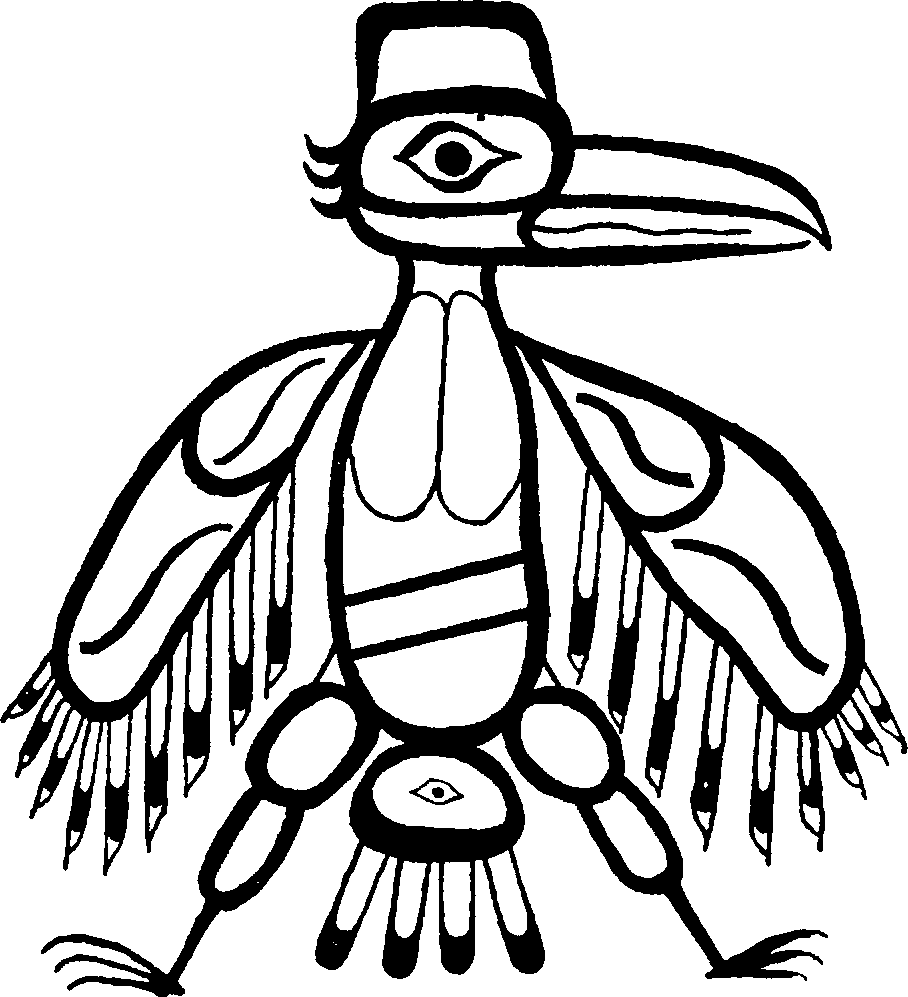

The author and the publisher wish to thank the following for their permission to quote material: Institute for the Arts, Rice University, for the lines from Bill Reid on pages of Indian Art of the Northwest Coast: ADialogue on Craftmanship and Aesthetics, by Bill Holm and Bill Reid (Houston, Texas: Institute for the Arts, Rice University, 1975; distributed by the University of Washington Press, Seattle); McGraw-Hill Book Company for an excerpt from the diary of Patience Loader as quoted in The Gathering ofZion by Wallace Stegner, copyright 1964 by Wallace Stegner; the New YorkTimes for lines from Times of the Males, by Wright Morris, the New YorkTimes Rook Review, January 1, 1979, 1979 by the New York Times Company. The four Haidah Indian designs, by James G. Swan, are reproduced from the Smithsonian Institution collections through the courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Doig, Ivan.

Winter brothers.

Based on the journals of James Gilchrist Swan.

1. Swan, James Gilchrist 2. Washington (State)HistoryTo 1889. 3 Makah Indians. 4. PioneersWashington (State)Biography. 5. IndianistsWashington (State)Biography.

I. Swan, James Gilchrist. II. Title.

F891.S972D64 9797'03'0924 [B] 80-7933

ISBN 0-15-697215-8 (Harvest: pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-15-697215-4

e ISBN 978-0-547-54673-5

v4.1015

Day One

His name was James Gilchrist Swan, and I have felt my pull toward him ever since some forgotten frontier pursuit or another landed me into the coastal region of history where he presides, meticulous as a usurers clerk, diarying and diarying that life of his, four generations and seemingly as many light-years from my own. You have met him yourself in some other formthe remembered neighbor or family member, full of years while you just had begun to grow into them, who had been in a war or to a far place and could confide to you how such vanished matters were. The tale-bringer sent to each of us by the past.

That day, whenever it was, when I made the side trip into archival box after box of Swans diaries and began to realize that they held four full decades of his life and at least 2,500,000 handwritten words. And what life, what sketching words. This morning we discovered a large wolf in the brook dead from the effects of some strychnine we had put out. It was a she wolf very large and evidently had five whelps. Maggs and myself shinned her and I boiled the head to get the skull.... Mr. Fitzgerald of Sequim Prairie better known as Skip! walked off the wharf near the Custom House last night and broke his neck. The night was very dark, and he mistook the way.... Jimmy had the night mare last night and made a great howling. This morning he told me that the memelose were after him and made him crazy. I told him the memelose were dead squid which he ate for supper very heartily.... Mr Tucker very ill with his eye, his face is badly swelled. This evening got Kichooks Cowitchan squaw tomilk her breast into a cup, and I then bathed Mr Tuckers eye with it....

I recall that soon I gave up jotting notes and simply thumbed and read. At closing hour, Swan got up from the research table with me. I would write of him sometime, I had decided. Do a magazine piece or two, for I was in the business then of making those smooth packets of a few thousand words. Just use this queer indefatigable diarist Swan some rapid way as a figurine of the Pacific Northwest past.

Swan refused figurinehood, and rapid was the one word that never visited his pencils and pens. When, eight, ten years ago, I took a segment of his frontier life and tried to lop it into magazine-article length, loose ends hung everywhere. As well write about Samuel Pepys only what he did during office hours at the British admiralty. A later try, I set out carefully to summarize Swanoyster entrepreneur, schoolteacher, railroad speculator, amateur ethnologist, lawyer, judge, homesteader, linguist, ships outfitter, explorer, customs collector, author, small-town bureaucrat, artist, clerkand surrendered in dizziness, none of the spectrum having shown his true and lasting occupation: diarist. This, I at last told myself, wants more time than I ever can grant it.

Until now. Here is the winter that will be the season of Swan. Rather, of Swan and me and those constant diaries. Day by day, a logbook of what is uppermost in any of the three of us.

It is a venture that I have mulled these past years of my becoming less headlong and more aware that I dwell in a community of time as well as of people. That I should know more than I do about this other mysterious citizenship, how far it goes, where it touches.

And the twin whys: why it has me invest my life in one place instead of another, and why for me that place happens to be western. More and more it seems to me that the westernness of my existence in this land is some consequence having to do with that community of time, one of the terms of my particular citizenship in it. America began as West, the direction off the ends of the docks of Europe. Then the firstcomers from the East of this continent to its West, advance parties of the American quest for place (position, too, maybe, but that is a pilgrimage that interests me less), imprinted our many contour lines of frontier. And next, it still is happening, the spread of national civilization absorbed those lines. Except that markings, streaks and whorls of the West and the past are left in some of us.

Because, then, of this western pattern so stubbornly within my life I am interested in Swan as a westcomer, and stayer. Early, among the very earliest, in stepping the paths of impulse that pull across Americas girth of plains and over its continental summit and at last reluctantly nip off at the surf from the Pacific, Swan has gone before me through this matter of siting oneself specifically