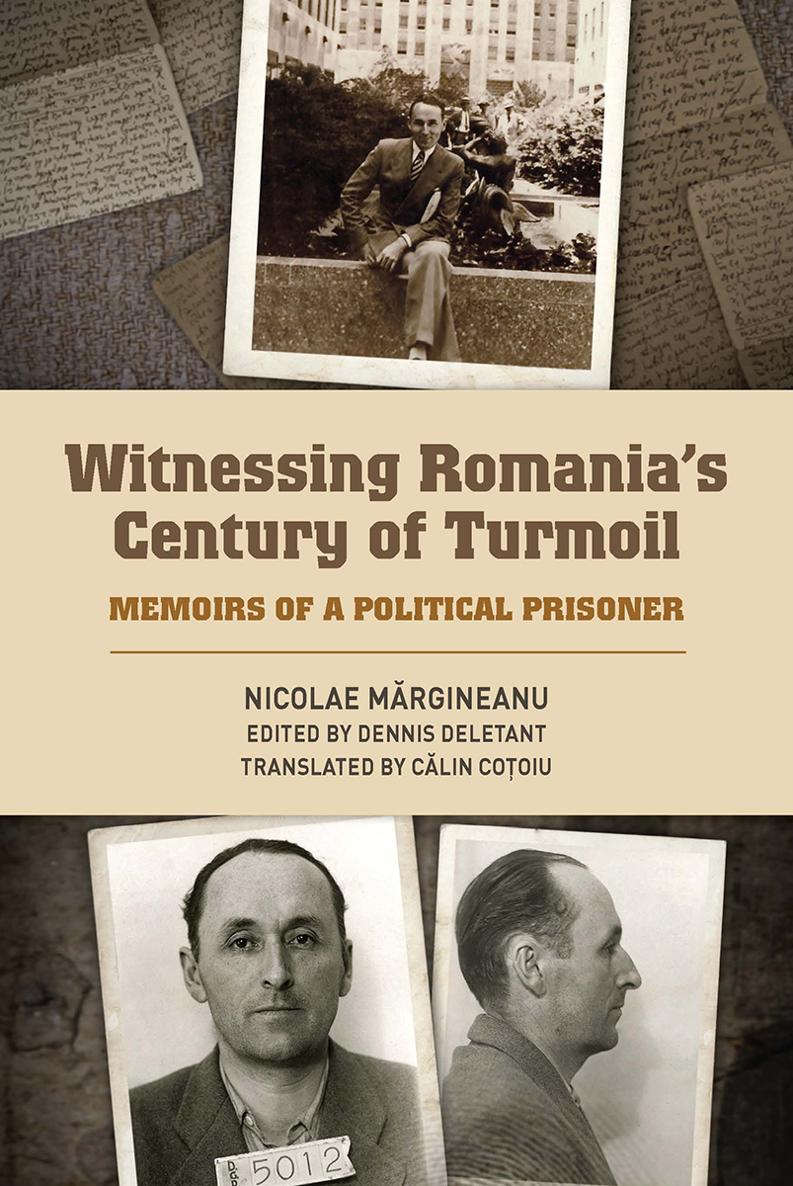

WITNESSING

ROMANIAS

CENTURY OF

TURMOIL

Nicolae Mrgineanus journey started in 1905 in the village of Obreja in Transylvania and ended in 1980 in Cluj-Napoca, Romania. He began his life under Austro-Hungarian rule, was witness to the 1918 Union, lived under three kings (Ferdinand, Carol II, and Mihai), and survived all of Romanias dictatorships, from absolute monarchy to the Legionnaires rebellion, the Antonescian dictatorship, and finally the years under Communist rule. Mrgineanu studied psychology at the University of Cluj and attended postgraduate courses in Leipzig, Berlin, Hamburg, Paris, and London. He was awarded a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship that enabled him to do research for two years in the United States, at Harvard, Yale, Columbia, the University of Chicago, and Duke. He returned to Romania and became chair of the psychology department at the University of Cluj.

In 1948, Mrgineanu was arrested on a charge of high treason, based on his alleged membership in a resistance movement against Communist rule. He was sentenced to twenty-five years imprisonment, of which he served sixteen, passing through the jails at Malmaison, Jilava, Pitesti, Aiud, and Gherla. This book, his autobiography, is a shocking testimony to the fate of the intellectual elite of Romania during the Communist dictatorship. It is a unique and invaluable addition to the literature in English on the experience of political prisoners, not only in Communist Romania but in authoritarian states in general.

Nicolae Mrgineanu (1905-1980) was a Romanian psychologist and writer who was a political prisoner during the period of Communist rule. Dennis Deletant is the Visiting Ratiu Professor of Romanian Studies at Georgetown University. Calin Cotoiu is a translator based in Bucharest, Romania.

Rochester Studies in East and Central Europe

Senior Editor: Timothy Snyder

Additional Titles of Interest

Nazi Policy on the Eastern Front, 1941: Total War, Genocide, and Radicalization

Edited by Alex J. Kay, Jeff Rutherford, and David Stahel

Critical Thinking in Slovakia after Socialism

Jonathan Larson

Smolensk under the Nazis: Everyday Life in Occupied Russia

Laurie R. Cohen

Polish Cinema in a Transnational Context

Edited by Ewa Mazierska and Michael Goddard

Literary Translation and the Idea of a Minor Romania

Sean Cotter

Coming of Age under Martial Law: The Initiation Novels of Polands Last Communist Generation

Svetlana Vassileva-Karagyozova

Revolution and Counterrevolution in Poland, 19801989: Solidarity, Martial Law, and the End of Communism in Europe

Andrzej Paczkowski

Translated by Christina Manetti

The Utopia of Terror: Life and Death in Wartime Croatia

Rory Yeomans

Kyiv as Regime City: The Return of Soviet Power after Nazi Occupation

Martin J. Blackwell

Magnetic North: Conversations with Tomas Venclova

Ellen Hinsey and Tomas Venclova

A complete list of titles in the Rochester Studies in East and Central Europe series may be found on our website, www.urpress.com .

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

N icolae Mrgineanus autobiographical memoir is a unique and invaluable addition to the literature in English on the experience of political prisoners, not only in Communist Romania but in authoritarian states in general. It graphically uses the authors incarceration (194864) to underline the arbitrary abuse of authority in Communist Romania and his courage in maintaining his moral integrity and dignity in the face of iniquity. But its appeal goes beyond his postwar suffering, for it offers a wistful and sensitive account of episodes from the authors youth in Transylvania in the period 191618. He was born in the village of Obreja in central Transylvania on June 22, 1905. As the first member of his peasant family and the only one of his generation from his village to attend a Romanian-language school in Hungarian-ruled Transylvania, his achievement underscores the challenges faced by Romanians in the province before the proclamation of its unification with Romania in December 1918. Mrgineanus subsequent professional success in academia in the interwar years and his distinction in his chosen field of psychology are engagingly described, while his description of the Soviet advance into Transylvania in fall 1944 and its impact upon the local population is a rare such testimony.

To explain the significance of these remarks, some historical background and context is necessary. The province of Transylvania was regarded by both Romanians and Hungarians as an integral part of their ancestral homeland, and in the minds of both peoples their own survival as a nation was linked to the fate of Transylvania. In this regard, the question of historical antecedence in Transylvania was invoked to buttress a political claim to control of the territory. Emphasis wasand isplaced on an uninterrupted Romanian presence in the territory of Romania, primarily in Transylvania. Most Romanian historians claim a continuous Romanian presence in Transylvania from the time of the Roman colonization of Dacia after its conquest by Trajan at the beginning of the second century AD. The Romans introduced into the province settlers from all parts of the Empire who intermarried with the local Dacian population and romanized it, thus producing the Daco-Roman people who were the forebears of the Romanians. This Daco-Roman settlement predated the arrival of the Hungarians in Transylvania at the end of the first millennium. After the Roman withdrawal from the province in 27175, the province became a gateway to the south for successive invaders, with the Daco-Romans seeking refuge in the mountainous regions, thus preserving their Latin language and culture. This explanation of the Romanian presence in Transylvania is known as the theory of Daco-Roman continuity.

Hungarian historians, on the other hand, discount the continuity theory by claiming that when the Romans abandoned Dacia its inhabitants accompanied them and by arguing that when the Magyars entered the Central Danubian basin at the end of the ninth century, Transylvanias only inhabitants were Slavic tribes. They point to the preponderance of Slavic place-names and to the fact that the first mention of Romanians (or Vlachs) in the documents of the Hungarian chancery occurs only in a charter of 1222. Here it should be stressed that obscurity envelops the other inhabitants of Transylvania since the earliest documents relating to the province date only from the twelfth century. The Hungarian crown extended its authority over the region by encouraging Szekler (a Magyar tribe) and German colonists to settle there during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The presence of a Romanian population is ascribed to immigration at the end of the twelfth century from south of the Carpathians, whence Romanian shepherds were given the right to settle in Transylvania by the Hungarian kings. During the late ninth century Hungarian (Magyar) tribes reached their present homeland and what was to become Transylvania. When the Hungarian ruler Stephen accepted Christianity and was crowned king in Budapest in 1000 AD, Transylvania became part of the Kingdom of Hungary. Following the defeat of the Hungarian king by the Ottoman Turks at the battle of Mohcs in 1526, the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom (153870) was founded, and from this, the Principality of Transylvania, after the signing of the 1570 Treaty of Speyer by John Sigismund Zpolya and Habsburg Emperor Maximilian II.