Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2004 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Louisiana Paperback Edition, 2010

Designer: Melanie OQuinn Samaha

Typeface: Minion

Typesetter: Coghill Composition Co., Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Billings, Warren M., 1940

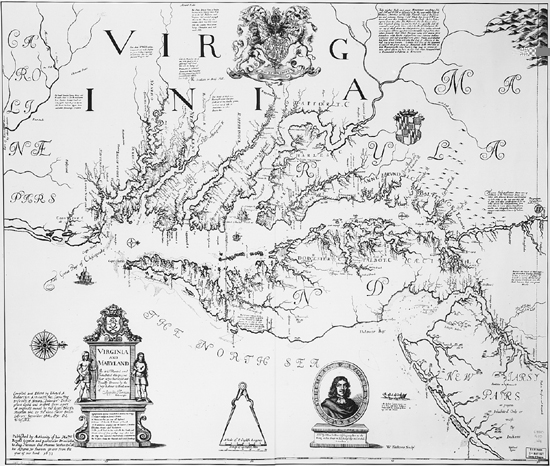

Sir William Berkeley and the forging of colonial Virginia / Warren M. Billings.

p. cm. (Southern biography series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8071-3012-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Berkeley, William, Sir, 16081677. 2. GovernorsVirginiaBiography.

3. VirginiaHistoryColonial period, ca 16001775. I. Title. II. Series.

F229.B53B55 2004

975.502092dc22

2004011060

ISBN-13: 978-0-8071-3443-6 (paper : alk. paper)

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of

the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council

on Library Resources.

PREFACE

Sir William Berkeley and I share an acquaintance of four decades and more. We first met during my undergraduate days at the College of William and Mary, the place where I initially sharpened my taste for early American history. I grew more familiar with him in the time of my apprenticeship as a doctoral student. Later still we were usually in each others company whenever I rummaged the records in search of a deeper understanding of seventeenth-century Virginians and their world.

His name was synonymous with Bacons Rebellionthe most serious challenge to British royal authority in North America before the American Revolutionbut our repeated encounters divulged another Berkeley. The Berkeley of my acquaintance dominated the Old Dominion as did few of its chief executives, colonial or modern. This Berkeley invented the General Assembly as a bicameral representative legislature, he spurred the rise of Virginias planter aristocracy, he promoted the development of Carolina, he rebuilt Jamestown, he almost diversified the colonys economy, and he turned himself into a Virginian.

So commanding a presence as his, it seemed to me, resulted from a singular conjunction of personality and place that explained not only Berkeley but the very shape of Virginia itself. The better I knew him, the greater became my appreciation of why no one ever attempted his biography or seldom probed his administration deeply. Berkeley was an enigmatic man. The challenge of writing about his life arose not so much from wrestling with an innately peculiar individual. Because his personal papers and official records were scattered, and most had vanished down the centuries after his death, the test lay in documenting the dimensions of his being. That realization dampened my enthusiasm and fended off the lure of taking him on as a subject for a book. Temptation finally got the better of me in the mid-1980s, about the time I finished editing the papers of one of his successors, Francis Howard, fifth baron Howard of Effingham, and I resolved to write this book.

The book could not proceed, however, until I tracked down and read all of Berkeleys surviving papers. Those artifacts, like so many potsherds from an archaeological site, lay obscurely tucked away in a field of manuscript repositories that ran from the United States to Sweden to the British Isles to the Netherlands and thence to the United States once more. My recovery of many items, I freely admit, resulted as much from luck as from my cleverness at detection. Individual documents, often as not, furnished the best clues to the identity or whereabouts of others. I transcribed each paper I found into a digital database that I initially intended as nothing more than a handy reference aid. This burgeoning trove found life in its own right, blossoming at length as The Papers of Sir William Berkeley, 16051677, which will appear in the future.

Pieced together, the extant documentary record yielded a surprisingly ample restoration of the vessel that once was the whole Berkeley, but, like a smashed pot dug from the ground, important bits of Berkeleys character and personality were beyond salvage. Most notably, massive destruction of his letters and other writings foiled any deep sounding of the interior man. It was not always possible, for instance, to fathom how he internalized cues that guided his mental processes, let alone how he thought or how his thinking took shape in action. Despite the missing pieces, the following pages depict Berkeley in ways never seen before, just as they illuminate my quest to understand him in the context of the colony he called home.

American scholars have long been guilty of misspeaking Berkeleys name. Customarily, they say Burke-lee, as in Berkeley, California. That was a pronunciation unknown to the governor or to his contemporaries, who said Bark-lee. Seventeenth-century Britons cast their phonetic interpolation in written form variously as Barclay, Barklee, Barkley, Barkly, Bartlett, Bartley, and, as the governor always preferred, Berkeley.

Direct quotations from original manuscripts are rendered according to the prescripts set forth in the section on selection, rendition, and annotation of documents in The Papers of Sir William Berkeley Web site, www.uno.edu/history/berkeley.htm. Obsolete usages are thus regularized only to the extent that modern orthography is imposed upon proper names, whereas archaic abbreviations and symbols are expanded, and sentences begin with capitals and end in appropriate terminal punctuation. Citations to case reports, law dictionaries, statutory abridgments, treatises, and other legal works of the period invariably refer to witnesses that are in my library. Biographical details about Virginians who appear throughout the book arise from an electronic database I compiled for colonial officeholders between 1619 and 1699. Derived from vital statistics, places of origin, kin connections, occupations, offices, and landholdings, the database goes uncited. Dates are rendered in the old style, meaning that they are ten days behind modern reckoning. Then, too, during the seventeenth century the English commenced a new year on 25 March, not 1 January. In the interval writers customarily employed double datesfor example, 1 January 1600/01. That usage is retained here, but 1 January is considered the start of any given year.

I avow my deep gratitude to the following individuals, whose advice, close commentary, and constant encouragement sustained me in immeasurable ways while the book took form. Colleagues at the University of New Orleans were unfailingly supportive. Gerald P. Bodet, Arnold R. Hirsch, and Joe Louis Caldwell, by turns my department chairmen, ensured a convenient writing environment. Marie Erickson, head of reference at the Law Library of Louisiana, proved singularly adept at efficiently filling numerous interlibrary loan requests that put vital, if sometimes recondite, books, journal articles, and other source materials at my fingertips. Barbara M. Tearle, sometime director of the Bodleian Law Library at the University of Oxford, helped in locating pertinent information within the university archives. The Reverend Thomas Buckley, S.J., was instrumental in arranging a contact with the Venerable English College in Rome, where I tracked down a vital clue to Berkeleys whereabouts during the early 1630s.