ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author extends his grateful thanks to the many people in Hawaii who provided assistance during the research for this book. In particular, Louise Storm and a number of other diligent staff at the Hawaii State Librarys Hawaii and Pacific Section; many patient and helpful staff at the Hawaii State Archives; Corine Chun Fujimoto, Curator of Washington Place, and her staff; numerous personnel at the Hamilton Library, University of Hawaii at Manoa, especially Map Technician Ross R. Togashi; Kamehameha Schools archivist Janet Zisk; Juria Kyoya and historian Tony Bennes at the Moana Surfrider Hotel, Waikiki; Frank S. Haines of the American Institute of Architects, Honolulu; and, at the Iolani Palace, Collections Manager Malia Van Heukelem, docent Dolores Leguinecke Oates, and Curator Stuart Ching.

Special thanks go to the Reverend Rod Waterhouse of Hobart, Tasmania, for sharing invaluable family information on John T. Waterhouse and Henry Waterhouse. And to William Kaiheekai Maioho, Curator of the Royal Mausoleum, Mauna Ala, Hawaii, for conducting my wife and myself through the mausoleum chapel and the royal crypt. To David Waipa Parker, I wish to extend most grateful thanks and profound respect for sharing his familys history. And to Francis K. W. Ching, I record my sincere gratitude for his patient guidance over several years, and for his valued friendship.

This book came together as a result of the unstinting encouragement and knowledgeable input of my New York City literary agent Richard Curtis. And most of all, this book would not have been possible without the dedicated involvement and sustaining support of my wife Louise, the power behind my throne.

There are only three places that are of value enough to be taken that are not continental. One is Hawaii, and the others are Cuba and Porto Rico (sic). Cuba and Porto Rico (sic) are not now imminent and will not be for a generation. Hawaii may come up for decision at any unexpected hour, and I hope we shall be prepared to decide in the affirmative.

US Secretary of State James G. Blaine,

to President Benjamin Harrison,

August 10, 1891.

As regards Hawaii we should take the islands.

Theodore Roosevelt, when US Assistant Secretary of the Navy,

to Captain Alfred T. Mahan,

May 3, 1897.

INTRODUCTION

The key was as big as a mans hand. And now Bill Maioho, Curator of the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna Ala, placed that massive piece of iron in the keyhole and turned it. The heavy black wrought iron gate, richly decorated with six gold seals bearing the coat of arms of Hawaiis kings and queens, swung open at the Curators hefty push. Bill turned to my wife Louise and myself, and gestured for us to enter the crypt, the burial place of men and women whose names had become familiar to me over years of research.

For a moment, I paused, looking around. There, sitting beneath the palm trees, was the Gothic-style Royal Chapel that Bill had just guided us through. Nearby, the Hawaiian flag fluttered on a flagpole in the warm morning breeze. This 2.7-acre plot at Mauna Ala overlooking Honolulu on Oahu is the only place in Hawaii where the US flag does not fly beside the Hawaiian flag. This is sacred Hawaiian land, and long has been.

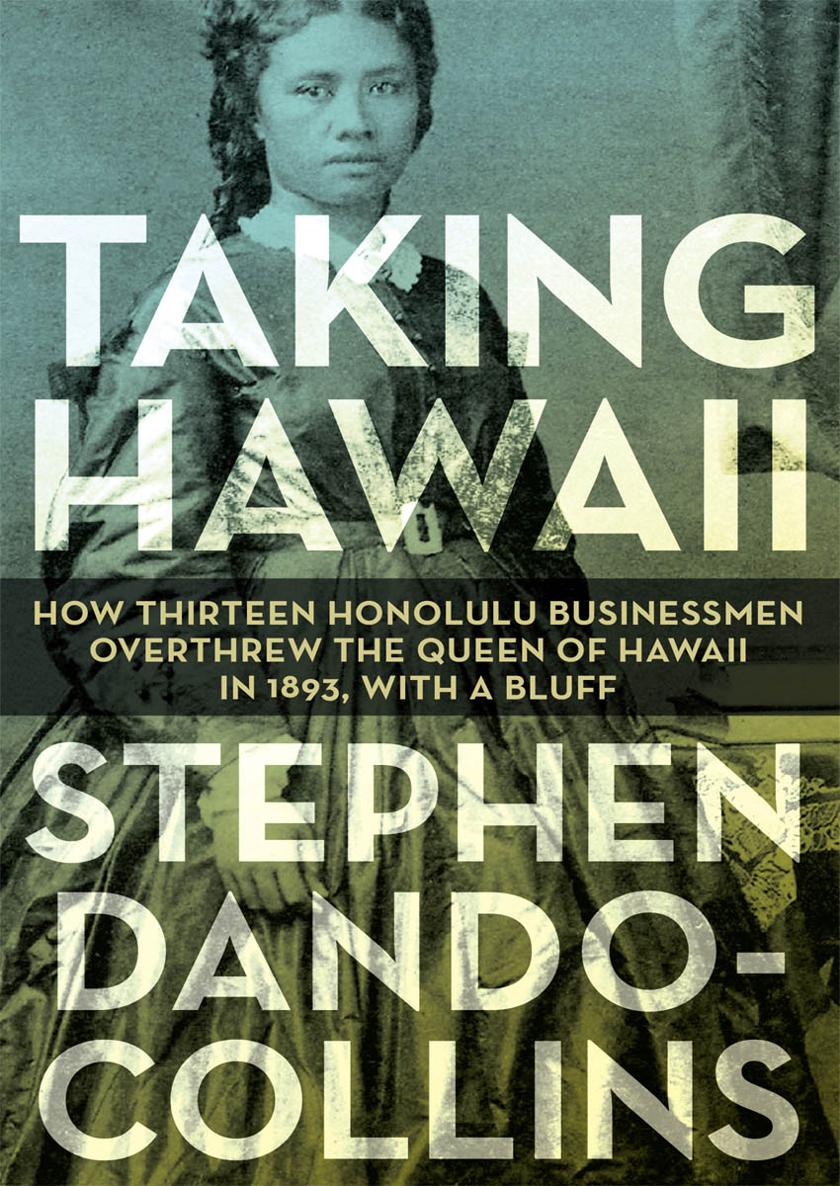

With a smile, Bill, who occupies his post as Curator here at the pleasure of the Governor of Hawaii, urged us to proceed. Louise and I walked down the steep stone steps and entered the underground space. The interior of the Kalakaua Crypt is not large. The white marble walls are inscribed in gold leaf with the names and dates of birth and death of twenty-one members of the Hawaiian royal family, whose remains are interred on the other side of the marble. I had come to see the final resting place of one former royal in particularQueen Liliuokalani, last ruler of the Kingdom of Hawaii.

There, high in the left-hand corner, was Liliuokalanis name inscribed in gold. Looking at it with respect and reverence, I felt that I knew her a little. I had read her autobiography. I had read her intimate diary entries covering her strife-torn life. I had read countless accounts of her by people who had known her, in books, newspaper articles, letters and official reports. I am not Hawaiian. I have been to Hawaii a number of times, but I am only a haole, a foreigner. To be brought down here into the sacred crypt at Mauna Ala was a huge honor for a haole. So, it was quite a presumption to think I might know, and understand, Hawaiis last queen. Silently, I asked Liliuokalanis forgiveness for this intrusion. Sometimes, when I visit a grave or a memorial, I feel a connection with the person who lies buried or is commemorated there. Yet, here I was not feeling any link whatsoever.

We emerged from the crypt, and Bill used his heavy key to lock the gate behind us. As we climbed back to the top of the steps, we saw a gardener waving urgently to us, then pointing to the sedan in which we had arrived. That sedan belonged to Francis Ching, our patient Native Hawaiian host here in the islands. As we hurried to the car, we saw that a rear window had been smashed. Louise gasped; she had left a travel bag on the back seat, thinking that here, in this holy place, it would have been safe. She was proven wrong. The bag had been snatched.

The police were called. Within minutes, a pair of blue and white Honolulu Police Department cruisers arrived. As we described our loss to the policemen, one of the Native Hawaiian officers shook his head, angry that a crime had been committed here, of all places. The ancestors will not be pleased, he said with a scowl.

Later, a local told us that if Native Hawaiians caught the people responsible for thisa band of Filipinos with a track record in this sort of robbery was immediately suspected by the policethey would be torn limb from limb. Bill, on behalf of his people, apologized profusely for the robbery, but we assured him he had nothing to apologize for, and thanked him for his kindness that morning. I was feeling for our host Francis, whose window had been smashed; but at least his car insurance covered the repair.

A few hours later, Louise and I were at the Iolani Palace, Queen Liliuokalanis former residence in Honolulu, trying to forget the stolen bag and the hassle of replacing its contents. Few visitors to Hawaii know this palace exists. Many longtime residents of Hawaii are equally ignorant of its existence, and its significance. It is not as if the building is hidden away. The Iolani Palace is in the heart of downtown Honolulu. Cars, taxis, buses stream past it, day and night. But ask a Native Hawaiian, and they will unerringly direct you here. The Friends of the Iolani Palace, a community group, saved the palace from destruction at the last minute in the 1960s, and slowly, painstakingly, proudly restored it, returning it to much as it had been when Liliuokalani lived and ruled here, at the same time retrieving looted palace objects from throughout the United States. Though grand in appearance, the Iolani Palace is the size of a gatehouse at many European palaces. Its a palace in miniature.